- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

The authors who took the challenge to describe the lives of Polish Jews are educators from the Jewish Historical Institute – Agnieszka Kajczyk, Olga Szymańska, dr Bartosz Borys and Deputy Program Director at the JHI, Anna Duńczyk-Szulc. Their everyday duties comprise working with school and university students from Poland and other countries, running courses for teachers and educators specializing in Jewish culture and history, and popularizing Warsaw and Jewish studies.

JHI: For the first time, we offer our readers a popular science book about the Oneg Shabbat group. Who may be interested in the book? Did you have any particular target group in mind?

Agnieszka Kajczyk: The book is dedicated to readers who had little knowledge about the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto or who encounter the subject for the first time. Thanks to clear structure, precisely explained terminology and names, the book will be an excellent source of information and can serve as a compendium on this subject.

Bartosz Borys: Initially, our plans comprised publications for teachers and educators who attend our courses, but we have quickly realized that there might be a much wider potential audience. We would like to address people who visit the JHI, who take part in our educational classes, walks, Thursday events and discussions.

Olga Szymańska: For students who attend our classes, this might be the first book about Oneg Shabbat. It will function as an adequate introduction into the subject, because the first two chapters summarize the themes of pre-war Jewish community and the establishing of the Warsaw Ghetto. In the following chapters, young readers will find many quotes from the witnesses of history — a source of knowledge more worthwhile than a standard textbook.

ŻIH: We hope that the book will reach as vast audience as possible. Many readers will certainly encounter the knowledge about the Warsaw Ghetto and the Oneg Shabbat group for the first time. What was the most difficult issue which required explaining in accessible language?

![02 — kopia.jpg [236.22 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/28/10e117d5d2beff60740de9fbf907ade0/jpg/jhi/preview/02%20—%20kopia.jpg)

![01 — kopia.jpg [354.84 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/28/41593b46a9aad5fe89f6631445efa95b/jpg/jhi/preview/01%20—%20kopia.jpg)

Anna Duńczyk-Szulc: We intended to publish the unique documents of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, such as photographs — one of the few, on a global scale, views of the ghetto „as seen by the witnesses”, namely by the imprisoned people themselves. In terms of illustrations, I have tried to follow the exhibition and various books published so far by the Institute. But on the other hand, we have also shown lesser known photographs as well. Some of them will be presented in this book for the first time.

BB: This subject has been discussed in many scientific publications, with bibliographies and the entire research apparatus, especially in the Complete Edition of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, published in subsequent volumes by the JHI. In order to attract the readers’ interest, who would be reaching for the first time by a book published by the Institute, we have written our book in an accessible, popular-scientific manner. We had to use clear language to describe complex processes. In cooperation with our graphic designer, we have developed a system of frames and highlights, which would bring attention to the most important issues, but without losing the reader’s focus.

OS: The Oneg Shabbat group was unique. We tried to present their activity in the conditions of the ghetto, to illustrate the power of an individual who uses their own spiritual resistance against the powers who try to exterminate it using all possible means, with determination and precision displayed in orders and bans. We can see it in the last part of the permanent exhibition at the JHI, when we walk between four displays in which we read about mass murder, deportations and death camps. The witnesses of these events and Oneg Shabbat members wrote about it all, and their singular accounts contribute to a panorama of those „hellish days”.

Even though your professions are different, all of you work in the area of education about the Holocaust of the Jews. How did your particular perspectives contribute to the content of the book?

AK: On one hand, we wanted our book to offer a „bird’s eye view”, and on the other — to present an individual perspective of a particular person, such as the members of Oneg Shabbat, their contributors, anonymous persons interviewed for example at the refugee points. This is why we have included many source materials. We give voice to the participants and witnesses of those events, we learn about their perspective, their emotions and feelings.

BB: I’m a historian, and commemorating things which I have considered importnat, for example particular facts from the history of the ghetto, became my obsession. I cared about unified terminology and references to statistical data. I wanted the book to be as precise as scientific publications.

OS: I cared about mentioning culture in the Warsaw Ghetto — a part of life which continued to exist in a way contrary to the depressing daily reality, marking softly lit, bright points of literary cabarets and theatres in the cardboard-grey landscape of the streets. A careful eye of our friend, a naturalist and geographer, proved to be useful in identifying the trees in the forests of Mazovia and verified the directions of the train networks. The book has been thoroughly researched in every aspect.

The circumstances in which the Ringelblum Archive was created involve also the stories of people. Is there any member of Oneg Shabbat that you had a particular bond with?

ADSZ: After almost three years since the opening of the exhibition, preceded by many months of working on its concept, I can say that I feel a particular attachment to Gustawa Jarecka. She was a writer and a teacher, who got a job as a stenotypist at the Jewish Council thanks to her very good command of German. She was passing reports from meetings and the German orders to Oneg Shabbat. One of the most shocking documents which she is presumed to be the author of was The last stage of resettlement is death, a report about the Great Deportation, written in September 1942.

Thanks to a preserved photograph of her I understand why Marcel Reich-Ranicki wrote that she was a beautiful and mysterious woman whom he was fascinated with. I have enormous respect for her. For a single mother with two children, surviving in the ghetto must have been a great challenge. People struggled for everything there, and children kept growing, they needed food and clothing. Her work for Oneg Shabbat is a proof of intellectual life that continued in the ghetto. In Jarecka’s case, such seemingly unimportant issues as literature and creativity suddenly became crucial. I also feel close to Henryk Bojm, photographer from the ghetto. I learned about his biography while working on the temporary exhibition, „The light of the negative”, last year. Bojm’s photographs used in our book were also an impulse to present the most recent discoveries about the authorship of the photographs, details of events, descriptions of documents. Decoding the mysteries of locations, position of the photographer, identity of people, circumstances of photographs taken required a very good knowledge of the ghetto’s topography. Thanks to cooperation between various departments of the JHI, we have complete captions, which provide another source of facts.

BB: For me, a special protagonist whom I have discovered while preparing to guided tours of the exhibition was Szmuel Szajnkinder – before the war, a footballer at the Warsaw „Hagibor” club (Hebr. „Hero”), and later a sports journalist at the Yiddish-language newspaper „Der Moment”. He participated in the September Campaign, defended Warsaw in the Praga district, and became a POW. When he left the camp and found himself in the Warsaw Ghetto, he worked at the Jewish Social Self-Help’s Popular Kitchen Central. He began his work for Oneg Shabbat in early 1942. What I found the most interesting in his reports were his notes about his comrades from September 1939, as well as about the moods among the civilians and the general atmosphere in the city. In his notes — only 2–3 weeks into the war — August 1939, let alone earlier times, seem far away, almost unreal.

AK: I don’t have one particular protagonist, because every member of the group was in my opinion special in their own way. Particular members had various duties: some were responsible for documentation (writing diaries, reports, statistics etc.), other collected materials (tore down German announcements, theater posters, took menus from restaurants, collected tram tickets, food stamps), other copied documents, collected funds, hired other members etc. Regardless of what their responsibilities were, they all believed in the meaning of what they did and it motivated them to keep going, even in the most dramatic circumstances — during the Great Deportation.

OS: The circumstances of hiding the first part of the Archive are particular. People who were there, teenagers Dawid Graber and Nachum Grzywacz, are especially close to me. Their teacher, member of Oneg Shabbat Izrael Lichtensztajn, received the task to bury 10 metal cases with collected documents. Dawid and Nachum, convinced that they participate in a breakthrough event, wrote down their testaments, which are a record of extreme emotions: fear for their loved ones, doubt in being saved from death, and eventually hope that „what we were unable to shout out to the world, we buried in the ground”. Despite having worked for several years at the Education Department, I can still hardly accept the word ‚testament’ in the context of teenagers. I think about the strength of spirit and the loneliness of these two boys who, in an extreme situation, asked us to remember about the murdered.

The work of the underground archivists from the Warsaw Ghetto is a beautiful example of spiritual resistance, whose power is rarely mentioned in the common narrative about World War II. Can the members of Oneg Shabbat become close also to today’s readers?

BB: I think so. Their actions show that in a seemingly hopeless moment, without a chance for armed resistance, one can keep a strength of spirit, sense of dignity and the meaning of one’s work. These are, in my opinion, timeless values, this is why the notes left by the members of Oneg Shabbat, often anonymous, tell as a lot not only about the times of the Warsaw Ghetto and the Holocaust, but also about the human condition in an extreme situation.

AK: Getting to know the story of a single person, their struggles, concerns, but also strength and determination — and our book certainly provides such perspective — may make members of Oneg Shabbat closer to some of our readers. After all, we all, living today or in the past, are the same. We feel sadness, fear, sometimes anger, but also a sense of solidarity, and the fact that even in extreme conditions, we have to keep the hope.

OS: It is true that writing a diary or copying statistical data is not as spectacular as battles, acts of sabotage or attacks on the criminals. Many people believe that anyone can write, and „real” heros are only those who were armed, as soldiers or as „forest partisans”. The inequality of these deaths was even described by Władysław Szlengel, a poet who cooperated with Ringelblum, whom we quote. Oneg Shabbat breaks the stereotype of wartime courage, showing that in those times, quiet activities of humble heroes, who also had to follow strict rules of conspiracy and risked being discovered, was key for discovering the truth.

ADSZ: This is our obligation. If we didn’t believe in it, we wouldn’t have taken this challenge! We continue the mission of pre-war historians who had worked in our building, and of Emanuel Ringelblum’s associates who were holding their meetings here during the occupation. We protest the memory of those whose names we read from the documents at the exhibition. Let us follow the message from their testament: „May this treasure make its way into good hands, may it live until better days, may it alert the world about the things that happened in the 20th century” — we would like as many readers as possible to remember together with us.

***

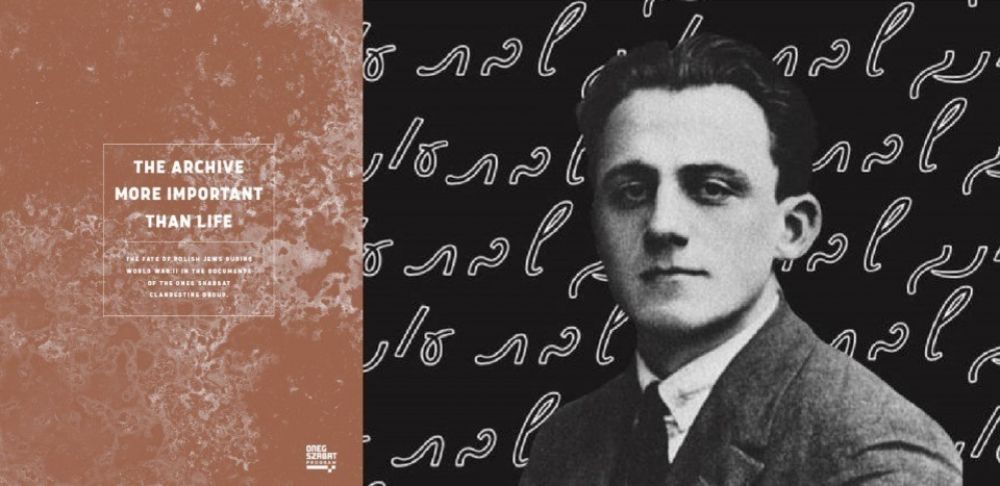

We offer you a book which — as we believe — can help you expand your knowledge about the history of Polish Jews during World War II. The book includes key information about the Warsaw Ghetto and the Oneg Shabbat group, founded by a historian, dr Emanuel Ringelblum. His group worked in secret, collecting an extensive documentation of life and death of the Jewish community during the German occupation. Presenting their achievements in a synthetic way, we try to discuss many themes related to the wartime fate of Polish Jews.

You will find explanation of basic terms, biographical notes, source materials from the Ringelblum Archive and rich illustration material: photographs and maps.

The publication complements the permanent exhibition, „What we were unable to shout out to the world”, and is a part of the Oneg Szabat Program, aimed at making available, and popularizing, the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto (the Ringelblum Archive) and commemorating the members of the Oneg Shabbat group.

See the book „The Archive More Important Than Life” in our online bookstore