- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

We don’t know much about Salomea Ostrowska. We don’t have information about where she came from, or even how did she join Oneg Shabbat.

She had been living in the Warsaw Ghetto at 27 Ogrodowa street, being employed at the Quarantine Service at 109/111 Leszno street. The quarantine was the threshold of the ghetto, a place of isolation for the Jews who were resettled to the ghetto, an entrance and an exit for the Jewish poverty. Inhabitants of the ghetto were also being held there in case of danger of an epidemic of diseases such as typhus. Brutal scenes were often taking place there, people were being held there for several days despite being in a good health condition; hunger, corruption and theft were widespread. In the quarantine, the despair and horror of Jewish life became fully revealed. Mothers losing their children, children squeezed and suffocated to death on the way (refugees from Grójec, February 1941). Husbands, sons and brothers sending desperate messages to their loved ones that they were taken away from the street, without clothing or money, holding on to bread tickets, to keys (April, May 1941)

The service, which began operating on 11 February 1941, was to support the employees of the quarantine, especially in terms of providing food and facilitating contact with families in the ghetto (carrying letters and parcels). She was writing about her work for refugees and displaced persons: We were working honourably. Being hungry ourselves, we still shared our bread with others. In the first part of the Ringelblum Archive, a testimony written by her – „Quarantine, 109/111 Leszno street”, was preserved. It was based on her observations from night shifts and daily reports of the institution.

![ostrowska_2_ARG-I-588_8.jpg [74.78 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/9dcff8dc9cadd64c4b19284d9217ccf6/jpg/jhi/preview/ostrowska_2_ARG-I-588_8.jpg)

Written in February 1941. Night and day, Jews from Polish towns and villages keep arriving, on trains, carriages, buses. They leave behind their homes, built over years of effort and hard work, to face hunger, poverty and unemployment. The quarantine is the threshold of their new life. The spacious rooms of the former school are grey withdirt, dust and human excretions. Travel-weary, hungry, they arrive in a place where they receive a cup of coffee and some bread – if it is available.

***

An individual person disappears in the giant human mass. People are crowded – one cannot tell one face from another. Yet still, everyone has their own problems and challenges. Everyone has requests which we cannot respond to. Everybody is hungry and asking for bread. Mother ask for food for their children, milk, or water with sugar for babies. Unfortunately, we often don’t even have bread, nor milk, nor sugar.

***

I look into the window and I think that it is true after all that bread has a golden colour.

***

Knocking on the door. Bath guard comes in. There are about 70 people in the bath, mostly children. They are so hungry that he is too afraid to let them into the bath. We still have semolina, so two ladies go to the kitchen to cook it and give it to the children.

***

An ambulance parked in front of the quarantine. They are taking away the sick and the elderly. They’re leading an elderly man. He has no shoes on. Assistants say that his daughter took away his shoes because she believes that it would be a pity to lose the shoes, and her father won’t survive anyway. [1] (translated by Olga Drenda)

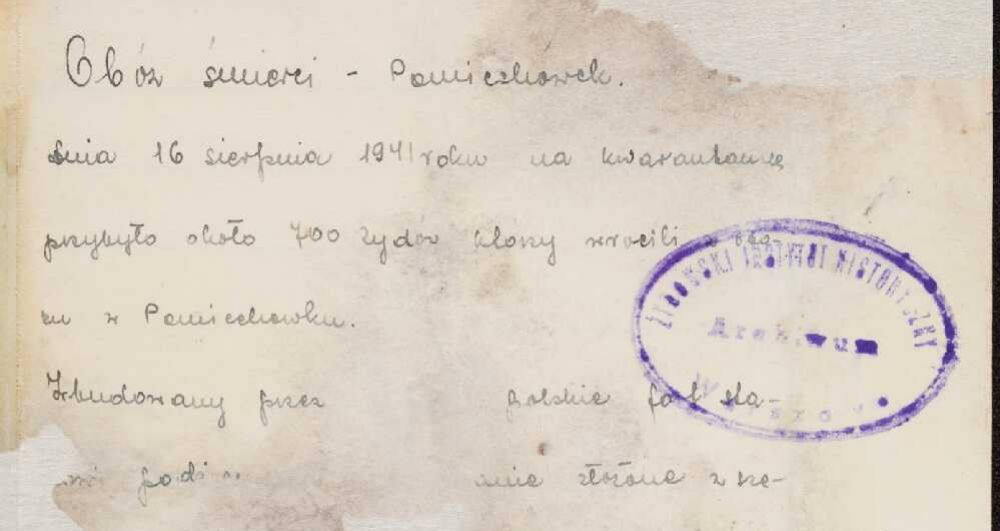

In the quarantine, Ostrowska had met former inmates of the camp for displaced persons in Pomiechówek. Together with Hersz Wasser and two other people, she was listening to the inmates and writing down their accounts. On the basis of 18 conversations, she wrote an essay – „Pomiechówek, the death camp”, which is the last part of „Quarantine, 109/111 Leszno street”.

![ostrowska_3_ARG-I-1163_6.jpg [86.94 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/77ef9c71392becf7d4f0b843a7b99494/jpg/jhi/preview/ostrowska_3_ARG-I-1163_6.jpg)

The inmates had to cope with famine, thirst and overcrowding, and aside from that, they were experiencing brutality from the guards, who were recruited usually from local volksdeutschs, plus a Jewish policeman Majloch Hoppenblum. The mortality among inmates was very high, also due to shootings or torture by the guards. Especially ill people, who were placed in a separate cell, had very low chance of survival. [2]

Ostrowska had also contributed more accounts to the Archive: testimonies from September 1939 and stories shared by the Jews who were escaping to the ghetto from the East (Vilnius and other directions) after 1941.

Ostrowska was writing in Polish, in a distinct, neat handwriting style, signing her works with her full name. She was receiving a small pay (her name is included in the Oneg Shabbat’s „Accounting Books”, from 9 September 1941 until 12 July 1942).

The date and place of her death remain unknown.

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

![ostrowska_4_ARG-I-1100_2.jpg [145.95 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/5cd702ea6792fd90843c437b6c6dfbc6/jpg/jhi/preview/ostrowska_4_ARG-I-1100_2.jpg)

Footnotes:

[1] The Ringelblum Archive, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, ed. Katarzyna Person, vol. 5, JHI, Warsaw 2011, p. 132 – 169.

[2] Introduction [in:] The Ringelblum Archive, Ostatnim etapem przesiedlenia jest śmierć. Pomiechówek, Chełmno nad Nerem, Treblinka, ed. Ewa Wiatr, Barbara Engelking, Alina Skibińska, vol 13, Wyd. UW, Warsaw 2013, p. 8.

Bibliografia:

Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017.

The Ringelblum Archive, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, ed. Katarzyna Person, vol. 5, JHI, Warsaw 2011.

The Ringelblum Archive, Ostatnim etapem przesiedlenia jest śmierć. Pomiechówek, Chełmno nad Nerem, Treblinka, ed. Ewa Wiatr, Barbara Engelking, Alina Skibińska, vol 13, Wyd. UW, Warsaw 2013.