- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

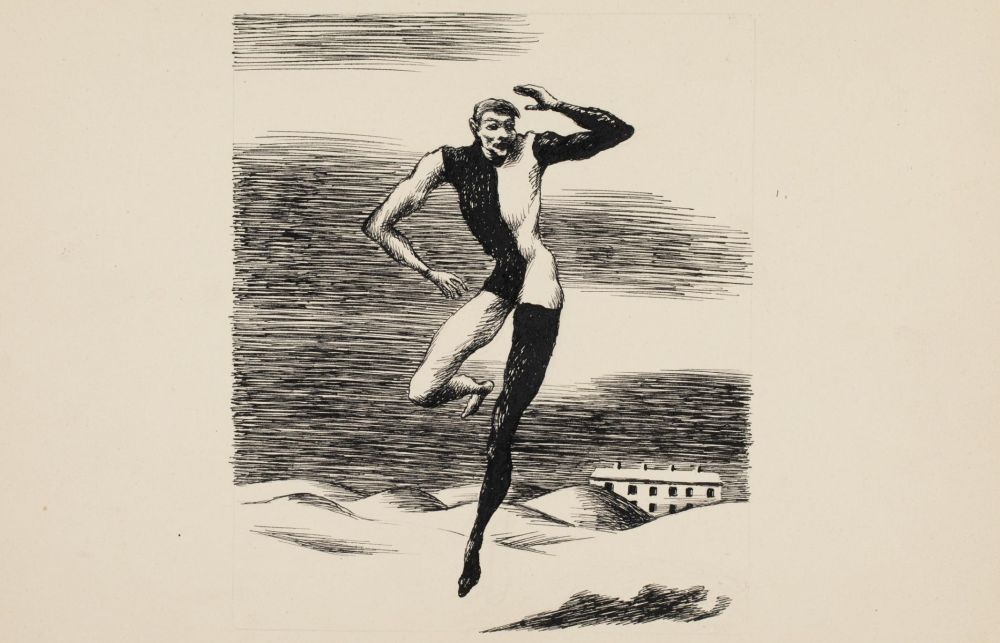

Mieczysław Wejman, Sketch for The Dancers [XI] (1944), privately owned

“There is also a clear division between the observed and observers, between actors/dancers/ acrobats and their reluctant spectators, between stage and audience. Some of the depicted characters are universal human types, a grotesque reflection of society as in commedia dell’arte, for example the characters of Harlequin or Columbine ” – adds Nader.

Presented works at the temporary exhibition at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute by Mieczysław Wejman, painter and graphic artist, known, among others, from the Cyclist series, created in occupied Warsaw at the turn of 1943 and 1944. For years, Dancers was interpreted as a universal story about the war apocalypse, but a more detailed analysis, revealing the unique context of the works, allows the graphics to be linked with the history of occupied Warsaw, the Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto, and victims of the spring 1943 uprising.

What does Wejman’s work tell us about the experience of the occupation in Warsaw? About those observed and those observing, about revelry and death?

![wejman_MN_1_comp.jpg [491.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/50fff1f345f0213782d86724d780c6de/jpg/jhi/preview/wejman_MN_1_comp.jpg)

Who was Mieczysław Wejman?

Mieczysław Wejman was born in 1912 in Brdów near Koło in Greater Poland. He studied at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Poznań and the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków. From 1937, he lived in Warsaw, receiving further education at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts.

During the occupation, he lived with his wife Maria and little son Krzysztof in Żoliborz district of Warsaw, on Promyka Street. He worked physically as a warehouseman in the “Jamasch” vodka and liqueur factory under German management, continued his artistic studies and exhibited his works at underground exhibitions. Shortly before the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising, the Wejmans, who were expecting a second child, moved to Izabelin near Warsaw, and after the uprising they went to Kraków.

After 1945, Wejman became a recognised artist, as well as an organiser of artistic life and education. He belonged to the group of “9 grafików” [9 graphic artists], in the years 1964-1970 he created the most important series of his career, Rowerzysta [The Cyclist]. For over 30 years he was a professor of painting and graphics at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, and he was also the rector of this university and the State Higher School of Fine Arts in Kraków. He died in Kraków in 1997.

Under what circumstances was the “Dancers” series created?

“During the war, Wejman produced over a hundred works: drawings, paintings, graphics, most of them were lost or destroyed. The preserved works usually focus on portraying family members, but some of them are landscapes, as well as extremely interesting characteristics of almost all social classes, relating to situations of danger, conspiracy, fear, hiding, or crowding in a small area” – writes Nader.

At the beginning of 1944, Wejman was hiding for several weeks or several months in an attic near his apartment in Żoliborz. The reason was a conflict with his supervisor at work, a Volksdeutsch (Pole with German roots who became a German collaborator), as well as the fact that his wife's brother, Stanisław Bełżyński, commander of the Kedyw ["Directorate of Diversion"] of the “Niwa” District of the Home Army, was wanted by the Gestapo. Although we do not know much about Wejman’s underground activity, the artist could not feel safe. In 1943, the Germans murdered professor Mieczysław Kotarbiński, with whom Wejman studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, in the ruins of the ghetto. Bełżyński, on the other hand, was killed by the Germans in May 1944. “The suffocating atmosphere of conspiracy, extortion, risky situations and shady characters had a powerful effect on the works of this period.”

![Wejman_Tańczący III (V) akwa_comp.jpg [496.26 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/0d05f91b38ccb9f3ba278d388855c95e/jpg/jhi/preview/Wejman_Tańczący%20III%20(V)%20akwa_comp.jpg)

It was most likely then – while in hiding – Wejman created the Dancers series, of which only some of the works and a few metal plates used for making prints have survived.

For Wejman, these were the first attempts at a new, demanding and at the same time culturally significant visual language (by among other things, reference to Goya’s deeply critical works). The Dancers become a screen on which to display and confront images, events, experiences and observations about the divided city and the “closed district” – the Warsaw Ghetto.

– writes Nader.

Before the war, the company “Jamasch”, for which Wejman worked, had Jewish owners, and its headquarters, bottling plant and warehouse were located at Pawia 49a, Pawia 66 and Rymarska 7 (now Bankowy Square) Streets, respectively. All of these locations were within the ghetto, close to its borders. “In order to reach the “Jamasch” company buildings Wejman, living on Promyka Street in Żoliborz, would have had the wall and the Jewish district almost constantly in sight from Stawki Street onwards, regardless of whether it was 1941, 1942 or even 1943.” – writes the exhibition curator Piotr Rypson, and adds:

People falling to the ground, leaping out of the windows of burning houses, are some of the most harrowing images from the ghetto uprising and the final liquidation of the Jewish quarter in Warsaw in 1943, known from several accounts. This was an atrocity also meticulously documented by a German photographer, some of whose photos were included in the report submitted by SS-Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop.

![powstanie_getto_plonie_jhi.jpg [259.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/b476f932363a8ac64f37975ba8b6660a/jpg/jhi/preview/powstanie_getto_plonie_jhi.jpg)

The disasters of war

“The artist’s works are full of puzzles, rebuses that are difficult or impossible to decipher, metaphorical labyrinths, and obscure references” – emphasises Nader. One of such references concerns the famous series’ by Francisco Goya, The Caprices and The Disasters of War. The first of the series of prints are 80 works from 1798-1799, in which the Spanish painter presents deformed images of the aristocracy and clergy. In the second, he showed the occupation of Spain by the Napoleonic army (1808-1814), the independence uprisings and their suppression by the French.

Goya several times depicted figures floating in the air, but the arrangement of falling persons in Dancers seems particularly similar to print No. 30 Los Desastres de la guerra. For the figure in Dancers III, dressed in a tunic resembling a sanbenito, we find related figures in Goya’s Capricho No. 80, as well as in the drawing Fantasma baile con castañuelas in the Prado Museum, showing a phantom dancing with castanets. The sanbenito costume itself was also found in Goya’s works devoted to the auto da fé ceremony.

![goya_estragos_de_la_guerra_comp.jpg [484.80 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/235d0e4bb3e58ef503b8e9dda8f6a49f/jpg/jhi/preview/goya_estragos_de_la_guerra_comp.jpg)

– writes Rypson. On the other hand, the sketches from the Folk Revelry series resemble the dancers from plate no. 12 of the Los Disparates series (Disparate allegre), and especially the crowd in the famous painting The Burial of the Sardine. “The seemingly cheerful festival closing the three-day carnival in Madrid is full of anxiety, uncontrolled violence, dark forces hidden under the masks of the dancing people," writes Rypson. Under the conditions of war, the reference to Goya acquires a special dimension:

The protagonists of his [Wejman’s] prints and sketches are defenceless people taking part in a kind of social theatre, their status emphasized by their distinguishing attire or nudity. These are people exposed to the gaze of onlookers. Thus, on a metaphorical stage there are the defenceless “others”, and next to them those who in various ways “set them in motion”, as well as those who regard them with more or less indifference. That is why my reading of Dancers is unambiguous: Mieczysław Wejman is recording the situation of Jews in Warsaw during the German occupation.

![goya_fantasma_con_castañuelas_comp.jpg [485.01 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/34260eaa1210ef69bf5c26258a2a0236/jpg/jhi/preview/goya_fantasma_con_castañuelas_comp.jpg)

Blurring and underlining the difference

Strikingly, Wejman’s series remained in the shadows for decades, not interpreted as a testimony of the Holocaust. “[F]rom practically the very beginning these works were described using an Aesopian language of concealment,” notes Rypson. It was influenced by the censorship of the People's Republic of Poland, which usually did not allow the highlighting of the extermination of Jews as a unique event, and especially limited the possibility of speaking about Poles’ offenses against Jews.

The interpretations of Wejman's series include terms such as “a surrealistic mood of the highest class ” (Jerzy Madeyski, 1969), “a well-developed fantasy, a mixture of the tradition of Goya’s Caprices, Proverbs (The Follies) and Visions of Madness with modern surrealism and symbolism” (Tomasz Gryglewicz, 2006), and “apocalyptic vision of man’s moral anguish and fall” (Małgorzata Krzyżanowska, 2014). While Madeyski, after the communist authorities’ antisemitic campaign of 1968, could not have spoken directly about the fate of Jews during the occupation, the lack of mention of them in Gryglewicz or Krzyżanowska’s comments is interesting. The fate of the Jews of Warsaw should not be ignored if we take into account how the uniqueness of the Holocaust was obliterated in the official historiography of the Polish People's Republic and how often it still remains on the margins of Poles’ consciousness today.

![goya_entierro_de_la_sardina_comp.jpg [497.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/300494a0bad1c3ed45b2015727bdd5e6/jpg/jhi/preview/goya_entierro_de_la_sardina_comp.jpg)

Wejman, “however, emphasizes in his series the difference between one and the other”, between Poles and Jews, ghetto inhabitants and observers, writes Rypson. – “He does so in various ways: by the theatricality of the depicted scenes, by differentiating certain characters by means of their costumes or lack of clothing, or by attitudes that show their alienation from the group.”

The monstrosity of the Holocaust, but also everyday life during the occupation were recurring themes in the artist’s memory, the records of which are presented for the first time in such a broad selection at our exhibition. (…) The expressiveness and repellent play of colours in such works as Ekshumacja (Exhumation) or W schronie (In the air-raid shelter) not only reflect the mood and horror of that time, but also reveal the sensitivity of the observer, who preserved for us these moving images of painful memories.

Sources:

Luiza Nader, Teatr i mur. Tańczący Mieczysława Wejmana [Theatre and the wall. Mieczysław Wejman’s Dancers] in: Tańczący 1944/Dancers 1944. Mieczysław Wejman, ed: Piotr Rypson, transl. Richard Bialy, JHI Publishing, Warsaw 2022.

Piotr Rypson, Kto tańczy pod murem? Wojenne grafiki i szkice Mieczysława Wejmana [Who is that dancing beneath the wall? Mieczysław Wejman’s wartime prints and sketches, in: Tańczący 1944. Mieczysław Wejman, op.cit.

__

Supported by the Norway and EEA Grants from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway and the national budget

![norweskie_belka_EN_od_11.2021.jpg [347.29 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/728739c11fac2ac0888ece903ada7662/jpg/jhi/preview/norweskie_belka_EN_od_11.2021.jpg)