- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

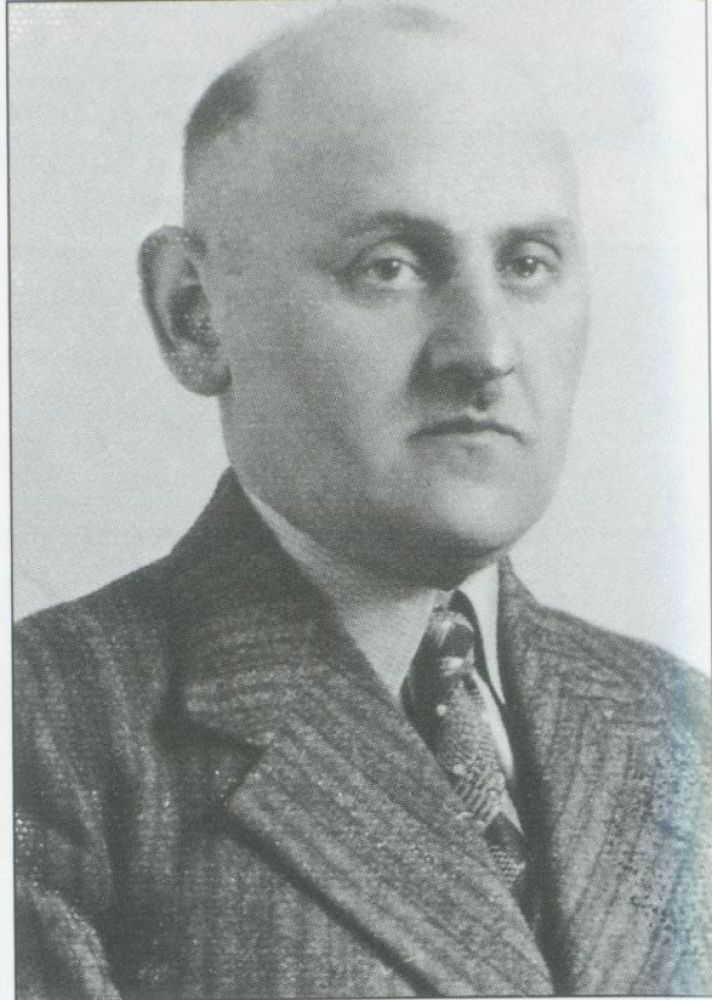

Eliasz (Eliahu) Gutkowski [1] was born in 1900 in Kalwaria, Lithuania, as a son of rabbi Jankiel (Jakub) and Sara-Lea, nee Witenberg. [2] Since 1907, he was living, along with his parents, in Łódź, at 46 Pomorska street. At the Polish Free University, he received a Master of Philosophy degree in history, and later taught in city schools in Łódź (Lodz), at the same time remaining active in Jewish charities and in the Poale Zion-Right Zionist party. [3] He had spent many years in the Palestinian land, became an expert on Hebrew culture [4], cooperating also with the YIVO Institute – a research unit dedicated to Jewish culture and history, established in 1925 in Vilnius. [5]

In 1939, the Gutkowski family – Eliasz, his wife Luba and son Gabriel – arrived in Warsaw as refugees. In the ghetto, they lived at 7/9 Muranowska street, apartment no. 5, and later at 31 Nowolipki street. Gutkowski worked at the Jewish Social Self-Help, and became one of Emanuel Ringelblum’s closest associates – the second secretary of the Oneg Shabbat group, after Hersz Wasser.

Gutkowski noted accounts from refugees, resettled people and former labour camp prisoners; he also copied and classified manuscripts, wrote weekly information bulletins (together with Wasser) addressed at Jewish and Polish underground press. He collected information about pogroms organized by the Germans in Lviv and in the Lublin region soon before the ‘final solution’. [6] Thanks to his encouragement, writer Perec Opoczyński became strongly involved in Oneg Shabbat’s activities. He also convinced poet Icchak Kacenelson, even though he wasn’t supportive of Poale Zion-Left [7], and Icchak Cukierman (Yitzhak Zuckerman), one of the leaders of the Jewish Combat Organization [8], who personally disliked Ringelblum – to donate their works to the Archive , by przekazywali swoje prace dla Archiwum. [9]

![gutkowski_2_ARG-II-480_36_gabriel_gutkowski.jpg [148.65 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/370e904693ae726f80079b9de5356b53/jpg/jhi/preview/gutkowski_2_ARG-II-480_36_gabriel_gutkowski.jpg)

Aside from that, he kept working for the underground press in his party, taught Jewish history at the Dror organization clandestine gymnasium, participated in talks about linking the JCO with the Jewish Military Union.

Gutkowski donated his school certificates to the Ringelblum Archive. These documents illustrate the growing up of a young Jewish intelligentsia member in Poland. The future teacher usually had moderate marks and had to take his closing exam twice. [10] He also left his letters, applications for work in the ghetto, requests for travel to Warsaw for his sister Rajzla, who lived single and suffered from hunger in the closed district in Łodź. Despite difficulties with supporting his wife and son, Gutkowski remained one of the most active Oneg Shabbat members.

Using his historian’s skills, he worked on a monograph dedicated to smuggling in the ghetto and currency exchange, in which dollars mattered the most [11]:

Currency transactions nearly always take place in a gate [of a tenement]. First of all, one has to study a note or coin carefully to establish if they’re not forged, and it takes one look away from a hasty seller for an alleged ‘buyer’ to run away with the offered goods. Shouts from the seller or even chasing the thief are not worth the effort. The thief’s associates take care of his safety. [12]

Gutkowski had a talent for finding information and for field research. When Rachela Auerbach began to work on an essay dedicated to a soup kitchen she ran at 40 Leszno street, he provided her with notebooks, writing equipment, small ‘remuneration’ paid by Oneg Shabbat to the authors. [13] Byłem zawsze szczery z Gutkowskim. I have always been honest with Gutkowski. He always passed received information to me, and he knew much more than Ringelblum, because Ringelblum didn’t meet with many people and didn’t collect accounts; he received most of the material from Gutkowski [14] – recalled Icchak Cukierman.

![gutkowski_6.png [403.55 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/f30b12ecb74c841036339781b209b533/png/jhi/preview/gutkowski_6.png)

Reports about the Holocaust

In February 1942, Szlama ben Winer, defector from Chełmno nad Nerem (Kulmhof), the first German extermination camp (where the Jews were killed using exhaust fumes from large vans), arrived in Warsaw. Hersz and Bluma Wasser helped him and wrote down his harrowing account, which was passed on to the Home Army, and later to London, already in March. Gutkowski, Ringelblum and Wasser joined a committee whose role was to gather and check information about extermination in occupied Poland, in order to alert public opinion in Poland and abroad. [15] At the time, the Oneg Shabbat group was the only source of information about Shoah for the Polish government in exile. [16]

In June 1942, Gutkowski heard an account from two female Jewish couriers who confirmed reports about another extermination camp in Sobibór. [17] Together with Ringelblum and Wasser, they wrote their report The Gehenna of the Polish Jews, describing mass deportations, conditions of life in ghettos, destruction of Jewish culture, beginning of mass murder. They had estimated the number of Polish Jews murdered at that time as, at least, 600,000. Samuel Kassow wrote that it was one of the first attempts taken by Jewish activists to describe and explain the Final Solution while it was taking place. [18] Deportations to Treblinka had begun soon afterwards.

When the Grossaktion Warsaw – deportation of nearly 300,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka death camp – began in summer 1942, Gutkowski, as many other Oneg Shabbat members, found shelter in the wood workshop, Ostdeutsche Bautischlerei Werkstatte, ran by Aleksander Landau at 30 Gęsia street.

Members of the group had nearly lost contact with each other during the deportation, but Gutkowski continued his work for the Archive nonetheless and tried to save his family. On 15 August 1942 Abraham Lewin, also from Oneg Shabbat, wrote down in his diary: The shooting began at 9:30 in the evening. Casualties on the street. Constant traffic from Pawiak prison and back all night. Gutkowski sends his only child, three and a half year old, to the cemetery, from where he is supposed to be carried safely to Czerniaków [district of Warsaw]. [19]

![gutkowski_7_gehenna.jpg [151.03 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/0cda83fe70181b29b00804c09eb51342/jpg/jhi/preview/gutkowski_7_gehenna.jpg)

Cukierman witnessed these events:

(…) on the farm [Polish farm linked to the JCO, which was selling vegetables to the ghetto] in Czerniaków, we have saved several dozen people who didn’t belong to the movement. One of them was Gabriel-Ze’ev, the little son of our friend Eliyahu Gutkowski. One day, during the great deportation from the ghetto, Eliyahu came to us, completely helpless: he had only one son, three years old. We took the child to Czerniaków and saved him. [20]

In early September, the Germans deported Gutkowski to Treblinka. On the train, he met Natan Asz and Michał Mazor, whom he worked with in the ghetto’s social care. When they noticed that the barbed wire covering the door was loose, they unblocked the door and jumped off the train. [21] Gutkowski returned to Warsaw. In November 1942, together with Ringelblum and Wasser, he wrote another report dedicated to the Great Deportation and Treblinka –The Destruction of Jewish Warsaw.

Eliasz Gutkowski, his wife and son died probably during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the April of 1943. They tried to leave the ghetto through the canals, but the Germans let toxic gas in – according to Icchak Cukierman. [22]

Written by: Przemysław Batorski

Translated by: Olga Drenda

![gutkowski_8_ARG-II-490_4_kartka_zywnosciowa.jpg [390.07 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/648d997b7df189d7492500c5924f6ebc/jpg/jhi/preview/gutkowski_8_ARG-II-490_4_kartka_zywnosciowa.jpg)

Footnotes:

[1] Basic information on Eliasz Gutkowski after: Katarzyna Person, Wstęp, in: Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 7, Spuścizny [Legacy], ed. Katarzyna Person, Wydawnictwo UW/Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2012, p. XVIII-XIX.

[2] Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 7, Spuścizny, op. cit., p. 360.

[3] In Poland, this Zionist, Socialist organization fought against discriminating Jews and supported the idea of founding a new, equal Jewish society in Palestine. In 1920, the Poale Zion party divided itself during its 5th Conference in Vienna, when part of its delegates voted against establishing contact with the 3rd Internationale (Comintern), an organization gathering Communist parties throughout Europe, founded by Lenin in 1919. The Right faction represented moderate Socialist views. Emanuel Ringelblum, Hersz Wasser and other Oneg Shabbat members belonged to the more radical Left faction, which renounced its links to Comintern in 1924.

[4] Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię? [Who Will Write Our History?], transl. Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2017, p. 272.

[5] Ibidem, p. 266.

[6] Abraham Lewin, Dziennik, transl. Adam Rutkowski, Magdalena Siek, Gennady Kulikov, edited by Katarzyna Person, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2015, p. 89-90.

[7] S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 537 (footnote 125).

[8] Ibidem, p. 272 (footnote 22).

[9] Ibidem, p. 273-274.

[10] K. Person, op. cit., p. XVIII.

[11] S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 275.

[12] A. Ben-Jaakow [Eliasz Gutkowski], report: ‘Czarna giełda’ [The Black Market], in: Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 34, Getto warszawskie, cz. II, [The Warsaw Ghetto, part II] ed. Tadeusz Epstein, Wydawnictwo UW/Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2016, p. 133.

[13] S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 251.

[14] Icchak Cukierman, Nadmiar pamięci (Siedem owych lat). Wspomnienia 1939-1946 [A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising], transl. Zoja Perelmuter, scientific edition Marian Turski, foreword by Władysław Bartoszewski, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warsaw 2000, p. 119.

[15] Barbara Engelking, Jacek Leociak, Getto warszawskie: przewodnik po nieistniejącym mieście, Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów, Warsaw 2013, p. 689.

[16] Ibidem, p. 687.

[17] S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 489.

[18] Ibidem, p. 494.

[19] A. Lewin, op. cit., p. 194.

[20] I. Cukierman, op. cit., p. 59.

[21] Kassow, op. cit, p. 275. Asz returned to Warsaw and died in the ghetto. Mazor survived the war and wrote a book La cité engloutie: (souvenirs du ghetto de Varsovie) [A city which disappeared: memories from the Warsaw Ghetto], Paris 1955. According to his memoir, the fourth man who jumped off the train, lawyer Mirabel, probably didn’t survive the escape.

[22] I. Cukierman, op. cit., p. 59.

Bibliography:

Ben-Jaakow [Eliasz Gutkowski], report ‘Czarna giełda’ [The Black Market], in: Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 34, Getto warszawskie, cz. II, [The Warsaw Ghetto, part II] ed. Tadeusz Epstein, Wydawnictwo UW/Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2016, p. 131-142.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 7, Spuścizny [Legacy], ed. Katarzyna Person, Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2012.

Icchak Cukierman, Nadmiar pamięci (Siedem owych lat). Wspomnienia 1939-1946 [A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising], transl. Zoja Perelmuter, scientific edition by Marian Turski, foreword by Władysław Bartoszewski, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warsaw 2000.

Barbara Engelking, Jacek Leociak, Getto warszawskie: przewodnik po nieistniejącym mieście, Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów, Warsaw 2013.

Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię? [Who Will Write Our History?], transl. Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wydawnictwo Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, Warsaw 2017.

Abraham Lewin, Dziennik, transl. Adam Rutkowski, Magdalena Siek, Gennady Kulikov, ed. Katarzyna Person, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2015, p. 89-90.