- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Abraham Lewin. Photo: courtesy of Ghetto Fighters' House, Israel

Abraham Lewin was born in 1893 in Warsaw. He received a traditional education, having learned in cheder and in yeshiva. He left the religious Jewish community at an early age – due to his father’s death, he had to earn a living for himself, his mother and three sisters.

In 1916, he began to work as a teacher of Hebrew and Judaistic studies at the Yehudia private gymnasium for girls in Warsaw, at 55 Długa street. He had met there Luba Hotner, teacher of Hebrew and his future wife, and Emanuel Ringelblum – founder of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto.

According to Kassow, students highly respected Lewin, who had a talent for bonding with them. A memorial book published by graduates is full of positive opinions about him. Nina Danzig-Weltser recalled: He was not only a teacher for us, but also a rich personality, a thinker. His looks emphasised this impression. Tall and slim, with fair hair and pale skin, he was speaking in a mild voice, in a restrained manner – apart from the Prophets, whom he interpreted with entusiasm, almost ecstatically. Lewin was very sensitive to the beauty of nature. During school trips, he had a habit of talking to students about the beauty of landscape. He was speaking not like a teacher, but like a friend to his equals. [1]

Luba was a daughter of a famous rabbi, Juda Lejb Hotner. She had lived for a short time in a kibbutz in Palestine, but due to health issues, she had to return home. She joined Hashomer Hatzair. Abraham and her had one child, daughter Ora born in 1928. Their plans of moving to Palestine had to be cancelled due to Luba’s fragile health and the birth of Ora.

During the interwar period, Lewin was active in pioneer Zionist organizations, oriented at liberal Zionism. He strongly believed in the significance of resistance through culture, he was also well educated in Jewish history and Hebrew language. His political views were different from Ringelblum’s, but they were linked by love for Jewish history and involvement in the Warsaw branch of YIVO. He was especially moved by the suffering of the „forgotten Jews”, the Jews who lived in poverty. [2] It shouldn’t be a surprise that his 1934 book „Kantoniści” (Cantonists) was dedicated to the subject of rekrutchina, conscription regime aimed at Jewish boys in the times of Tsar Nikolai I (1825–1855). Kassow recalls that Lewin was inspired by at excerpt from a memoir by famous Russian revolutionist Alexandr Hercen, who described a convoy of young Jewish boys who probably weren’t supposed to see their homes ever again. [3] Lewin wrote:We should collect all the tears of Jewish children from these days into one cup and lay it next to other cups with our blood and tears shed during previous persecutions. Out people should never forget about their martyrs. [4]

When the war began, he remained in Warsaw and found employment at the Jewish Social Self-Help, as the head of the youth commission. Together with his wife, they were teaching during the Yehudia secret classes.

From the very beginning, he had belonged to Emanuel Ringelblum’s group of closest and most trusted associates. [5]

Every Saturday, we – a group of Jewish social activists – meet and discuss our diaries and chronicles. We want our suffering, these labour pains of the Messiah, to be descibed for the memory of future generations, and for the entire world (…) These stories make my soul hurt, my head aches, as if a lead weight was pressing on it. [6]

He had particular contributions in copying the archived documents. He was signing them as „Nowolipie”, after his street in the ghetto. He was also donating to the Archive accounts of conversations with refugees coming to the ghetto. Some of them were published in the Oneg Shabbat bulletin.

The most important document he left is his Diary – an extraordinary testimony of living through the Great Deportation, and a harrowing account of a personal tragedy – deportation of his beloved wife to the Treblinka extermination camp. On 12 August 1942, during the blockade of 30 Gęsia street, she was taken to the Umschlagplatz, while Abraham was left alone with daughter Ora.

Ringelblum appreciated Lewin’s work due to his clarity and concise style, precision and truthfulness in relating facts. He believed that the Diary should be classified as a valuable literary document, which should be published as soon as possible after the war. [7] He also wrote: Our colleague Lewin has been writing his diary for one year and half now, putting all his literary creativity into it. Every sentence seems perfectly tailored. Lewin includes there everything he manages to hear not only about Warsaw, but also the horrible suffering of the Jews in the country. Even during the deportation, despite his great loss – his wife Luba was deported – he kept writing his diary, in conditions impossible to work and create in. [8]

The Diary ends suddenly on 16 January 1943, one day before the January deportations. The diary was buried together with the second part of the Ringelblum Archive.

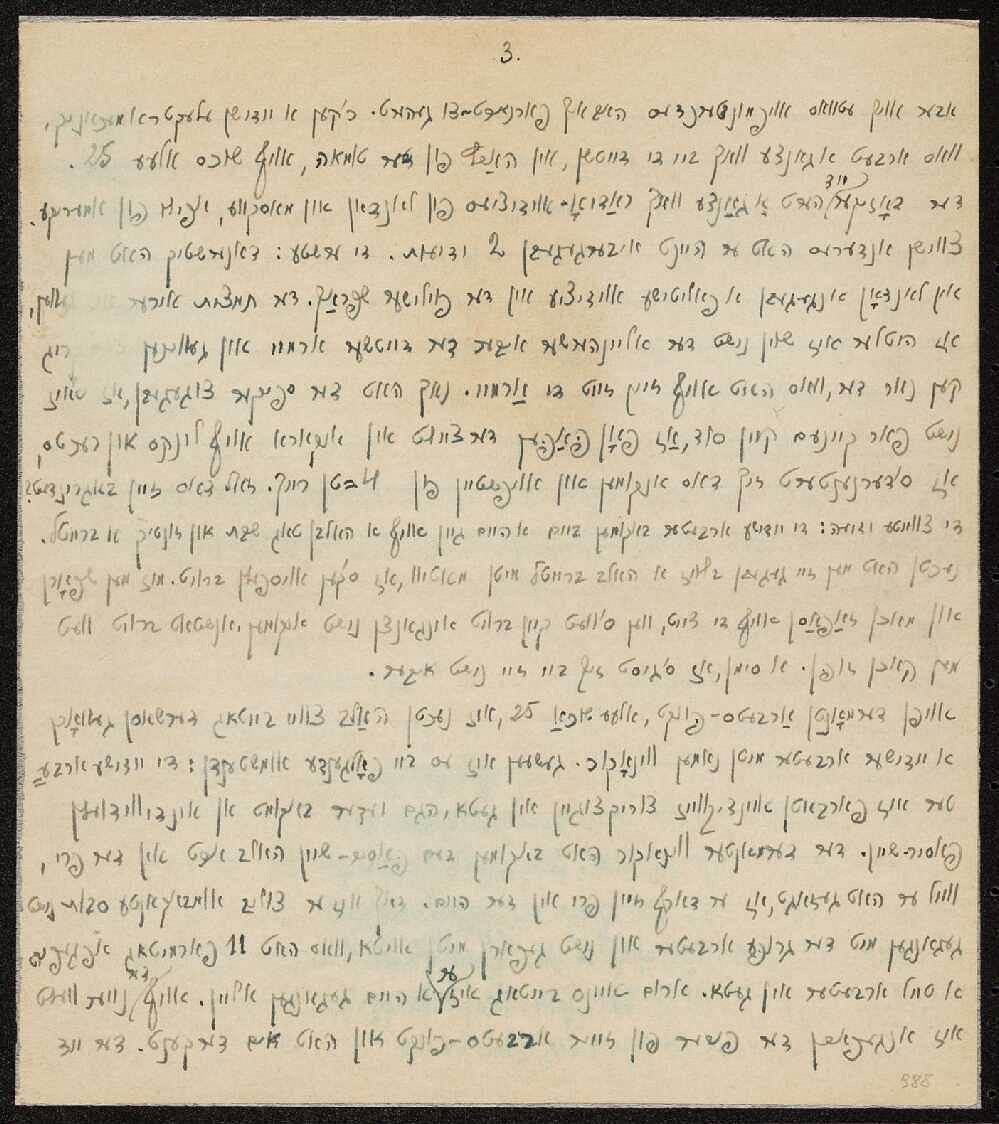

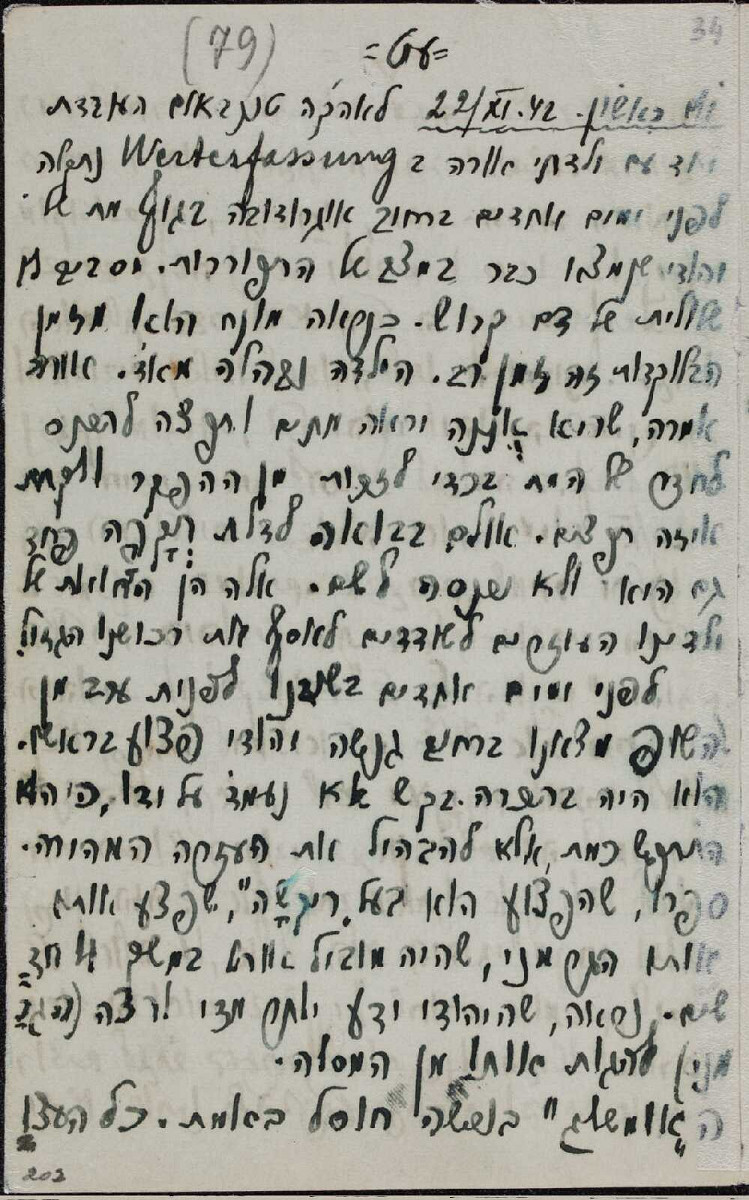

The Diary

The Diary covers a period of 10 months: from 26 March 1942 to 16 January 1943. it is divided into two parts: the first one (26 March – 10 July) was written in Yiddish and provides a description of the life in the Warsaw Ghetto before the Great Deportation, as well as a report from information about the fate of the Jews in other cities, according to news arriving in the ghetto. The second part of the diary (22 July – 16 January 1943) was written in Hebrew and is dedicated to the Great Deportation in the Summer of 1942 and the life in the remains of the Warsaw Ghetto. [9] The author was also participating in interviews with defectors from Treblinka – Dawid Nowodworski, Jakub Krzepicki and Jakub Rabinowicz. The culminating point of the diary is the information about Luba Lewin being taken away to the Umschlagplatz on 12 August 1942.

My sun is gone, darkness has covered my world. During the blockage at 30 Gęsia street, they have taken my Luba away. (…) I have no words to express my tragedy. I should have followed her, I mean – died. I have no strength to take this step. Ora… and her tragedy, a child who needs her mother so much. How much she loved her! [10]

The pain after the loss of his loved ones had been increasing with each day. In late October, he noted: I have lost my dear sister, I have lost so many beings dear to me! Yet their loss doesn’t strike me with as much pain as the loss of my life companion, with whom we have shared more than 22 years. The circumstances in which she had left our isle of tears increase the suffering, I’m about to lose my mind. [11]

The diary is filled with a sense of dread, of a tension in waiting for death. Lewin was aware that he was describing the end of the Jewish community. He wrote about fear directly, named it, often referring to a metaphor of pressure onto heart and mind, a weight, a sense of choking,a loop strangling one’s neck. The thought of the situation in which the Jews had found themselves in, including himself, makes his head ache and brings him close to madness. [12]

Whenever I hear news like this, I feel like my throat is choking, and that a heavy weight presses onto my heart. Black fear strangles and squeezes. We are getting close to the abyss, the mouth of the apocalyptic beast, whose forehead carries the words of: death, destruction, annihilation and pain of agony. [13]

For him, it is not the death which is the worst, but the uncertainty, waiting and fear of it. He is at the very end of his means to react to an endless line of misery. [14] There is no relief, even for a while, no consolation.

Constant uncertainty, constant fear are the worst feelings of all our sufferings and tragic experiences. If we survive this horrible war, and when we will consider in retrospect the war years as free people and citizens, we will for sure agree that the most exhausting, the most destructive thing for our health and our nerves was this constant living in fear and terror of naked life, the constant balancing on a line between life and death, a state in which our hearts were in danger of literally breaking out of terror at any time. [15]

Lewin was trying to reduce fear by searching for continuum with the history of persecution of the Jews [16], o get used to the fact that death is inevitable. [17] Many times, he was expressing respect and admiration for people who decided to follow their loved ones on their way to death. He felt remorse that he didn’t go with his wife. He was also decrying the loss of sensitivity, increasing obliviousness. He described the fate of children quietly waiting for their deaths or elderly people who have nowhere to go and go to Umschlag on their own. [18]

My mother’s situation makes me deeply sad as well. What should I do about her? I agreed that it would be better to put her to sleep forver rather than pass her into the hands of the murderers. But Jakub Tombak doesn’t agree to do this. Satan hiself wouldn’t be capable of coming up with a situation like this. [19]

The striking feature of Lewin’s writing is particular care to save and record as many names of innocent victims. Lewin asks about actual names, adds the name of a killed person after a few days, or leaves a blank space in order to complete details – name, age, family situation. He feels responsible for every person. [20]

He kept complaining about the lack of words which could convey the things that happen, which could help him judge, qualify. He often recalls Dostoyevsky or Bialik, wondering if they could be able to convey the scale of the tragedy which affected the Jewish nation. The human language proved to be to weak in the face of the Germans’ cruelty; there were no words to describe the Holocaust. Searching for metaphors or comparisons was pointless, as it was beyond imagination, without precedent. The only possible thing was to present naked facts, without decoration. [21]

Despite these declarations, the language he was using was filled with facts, but at the same time alive, descriptive, conveying the atmosphere of the ghetto streets, abandoned apartments, people trying to hide, living in fear. The ghetto is shocking with the great number of thin, pale faces. Some people are looking as if they were buried in their graves for a few weeks already. They are so appalling that they make us tremble instinctively. [22]

Lewin’s diary provides an image of a daily struggle for living and surviving, a battle against the cruel reality, but also against one’s own fear. Thanks to Lewin, we have received a priceless image of an unimaginable, undescribable suffering.

(translated by Olga Drenda)

Footnotes:

[1] Samuel B. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017, p. 302.

[2] Ibidem, p. 303.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Ibidem.

[5] Ibidem, p. 309.

[6] Abraham Lewin, The Diary, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2016, p. 105.

[7] The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, ŻIH, Warszawa 2018, p. 513.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] Katarzyna Person, „Przelewają naszą krew bez ustanku, niby wodę”. Dziennik Abrahama Lewina z getta warszawskiego, JHI, Warsaw 2016.

[10] Abraham Lewin, The Diary, op. cit., p. 191.

[11] Ibidem, p. 237.

[12] Ibidem, p. 59.

[13] Ibidem, p. 47.

[14] Ibidem, p. 120.

[15] Ibidem, p. 47.

[16] Katarzyna Person, „Przelewają naszą krew bez ustanku, niby wodę”. Dziennik Abrahama Lewina z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p. 16.

[17] Abraham Lewin, The Diary, op. cit., p. 219.

[18] Ibidem, p. 201.

[19] Ibidem, p. 205.

[20] Paweł Śpiewak, Przelewają naszą krew bez ustanku, niby wodę, a record of the meeting dedicated to Lewin at the JHI, https://www.jhi.pl/blog/2018–01–24-relacja-ze-spotkania-poswieconego-abrahamowi-lewinowi-jednemu-z-c....

[21] Abraham Lewin, The Diary, op. cit., p. 119.

[22] Ibidem, p. 61.

Bibliography:

The article was based on:

Katarzyna Person, „Przelewają naszą krew bez ustanku, niby wodę”. Dziennik Abrahama Lewina z getta warszawskiego, ŻIH, Warsaw 2016.

Abraham Lewin, Dziennik, ŻIH, Warsaw 2016.

The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, ŻIH, Warsaw 2018.

Samuel B. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Marta Młodkowska, Gettowe trajektorie. O zapisie osobistego doświadczenia w dziennikach z getta warszawskiego (Abraham Lewin, Rachela Auerbach, Janusz Korczak), http://rcin.org.pl/Content/57580/WA248_71427_P-I–2524_mlodkowska-gettowe_o.pdf