“What we could not shout out to the world, we buried in the ground” – wrote Dawid Graber in his will on August 3, 1942. When the Warsaw ghetto was liquidated in the SS-organized deportation of 300,000 Jews to the gas chambers of Treblinka, Izrael Lichtensztajn, director of Borochów school, with the help of 19-year-old Graber and 17-year-old Nachum Grzywacz, hid in the school basement at Nowolipki 68 Street the first part of the Ringelblum Archive. Graber and Grzywacz probably died in the same month, and Lichtensztajn was killed during the ghetto uprising.

![szczekaczka_zw_1.jpg [579.41 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/1/df30c60ea60e52f2cea258c63daa084c/jpg/jhi/preview/szczekaczka_zw_1.jpg)

10 metal boxes with around 21,000 cards containing priceless information and reports about the Holocaust were discovered in September 1946.

The second part of the Archive was discovered by accident in December 1950. The work of Emanuel Ringelblum and his associates was not in vain – a huge, unique collection of documents is available to historians, researchers and anyone who wants to learn about the fate of Jews persecuted in Nazi-occupied Europe and the history of the “Final Solution”.

![OS_grupa_12_rown.jpg [245.31 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/14/232f0b7c20c3ecba9ae83246cdabe4a0/jpg/jhi/preview/OS_grupa_12_rown.jpg)

“Almost everyone who created documents, arranged them, rewritten them – were killed” – writes in the curatorial essay Professor Paweł Śpiewak. – “The archive spoke by itself, it speaks with the voices of the dead.” It speaks for the most part in Yiddish, the language almost forgotten as a result of the Holocaust.

“It is vital to describe the deportations to the camps not from the perspective of historians who know how it all ended, but from the perspective of terror, uncertainty, the screams of people pushed onto the loading yard, and then to the death trains.”

Since 2017, at the Jewish Historical Institute, we have been presenting a permanent exhibition devoted to the Ringelblum Archive and its creators – among them journalists, writers, teachers, clerks, students, refugees and many anonymous people. The exhibition, though compiled by historians, speaks through the voices of witnesses, victims, those who were on the spot, in the hell of the ghetto and death camps.

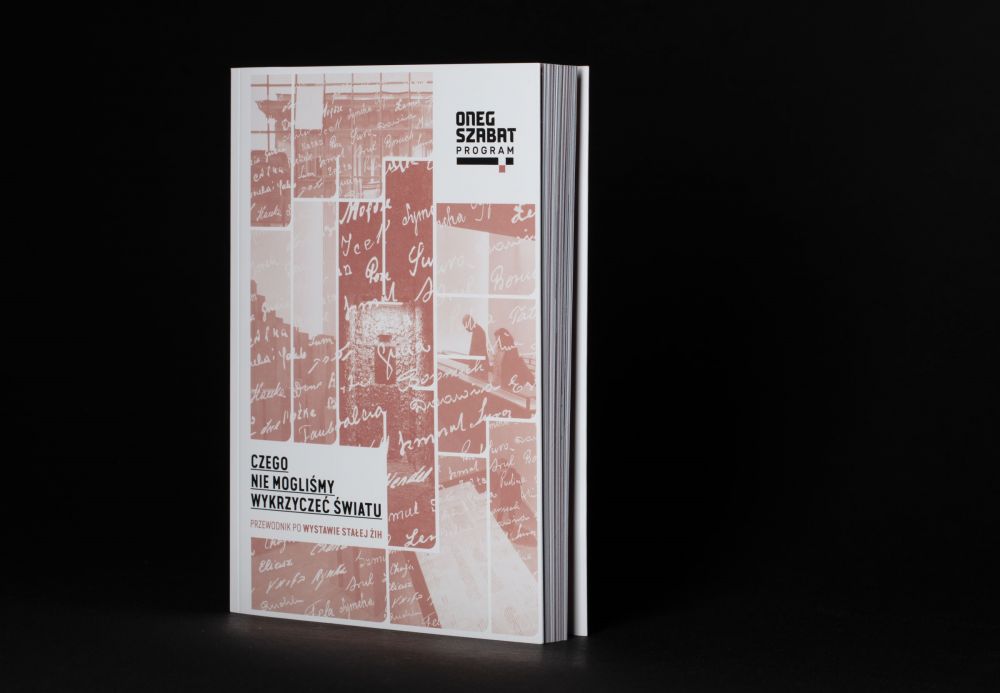

The guide includes an essay by Professor Paweł Śpiewak, former director of the Jewish Historical Institute (2011-2020), interspersed with photographs and fragments of reports, journals, and school papers from the Warsaw Ghetto.

The publication also includes biographies of members of the Oneg Szabat group and the exhibition guide, written by Zofia Fliszkiewicz from the JHI Library. It presents the history of the Institute’s building, which housed the Main Judaic Library before the war, and discusses the layout of the exhibition and the units on display: documents from the Ringelblum Archive, such as an invitation to a performance at Janusz Korczak’s orphanage, Stanisław Różycki’s report Street Pictures of the Ghetto. Naked corpse and naked facts, excerpts from Rachela Auerbach’s diary.

I cross Śliska Street in the early morning. At the exit of Komitetowa Street I am struck by the picture which I see every day, which has become commonplace: on the pavement there is a body of a tiny girl. So I am struck by the fact that the child’s corpse is lying naked. Have the beggars already taken the rags she was clothed in? Meanwhile, before I get to the place, “merciful” people perform a macabre ghetto ritual, already sanctified by tradition, namely, they are covering the body with a newspaper, holding it at the sides with stones.

(…)

At the cigarette seller, whom I carefully pull on the questions, I managed to get some information that shed light on a gloomy, plaguing mystery.

— Well, that’s Hesia from the neighbors (points to the house, mentions the yard, hall, floor), she was 14 (and she looked as if she was not 10), she died tonight…”

— from the report The Naked Corpse and Naked Facts by Stanisław Różycki

![OS_belka.jpg [57.58 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/3/07eb16efe9ce52a851e48899a8f87e0f/jpg/jhi/preview/OS_belka.jpg)

![koret_logo.jpg [20.68 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/1/28/7b5fd1e0015354b73f8515474d8171fb/jpg/jhi/preview/koret_logo.jpg)

![MKiDN_bialy_logotyp_strona_ŻIH_EN.png [10.32 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2023/1/12/0fbb15388d1a5d89c65891b6ce66941c/png/jhi/preview/ZNAK%20ENG.png)