- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

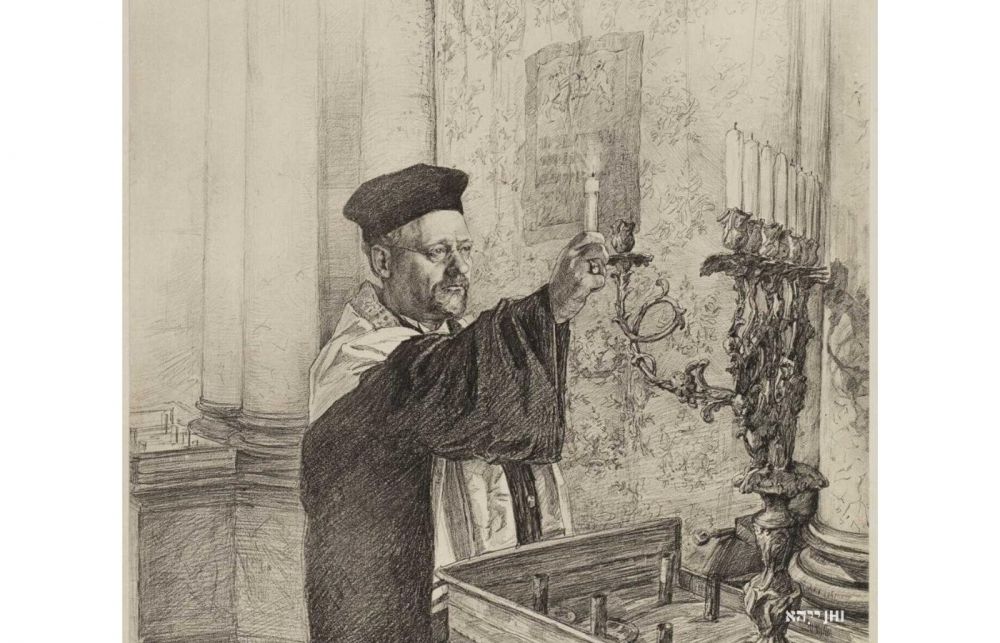

Lithography print (fragment) titled "Hanukkah” by Wilhelm Thielmann (1868–1924), German graphic artist and painter. It depicts a rabbi lighting a Hanukkah menorah at the synagogue. JHI collection

The history of Hanukkah – where did it all begin?

Hanukkah today is known to be a joyous holiday; beautifying our homes with candles, singing, celebrating, and a lot of food! Often, non-Jews see this time as an equivalent to Christmas, due to gift-giving and decorations. The story of how Hanukkah came about, however, with its roots in a revolution against assimilation and suppression of the Jewish religion, is not exactly a joyous one.

During the Second Temple era, when Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, Syria and Judea, he allowed the people under his rule to continue observing their religions. Under this rather benevolent rule, many Jews assimilated, taking on a lot of Hellenistic culture, including language, customs, and fashion.

Over a century passed, and Antiochus IV, a successor of Alexander the Great, came into power. He severely oppressed the Jews. Many of them were massacred, Jewish religious observance was forbidden, a Statue of Zeus was placed in the Holy Temple, and the requirement of sacrificing pigs, a non-kosher animal, on the altar was put into place, desecrating the Holy Temple. Antiochus was opposed by two groups: one lead by Mattathias the Hasmonean and his son Judah Maccabee, and a religious traditionalist group known as the Chasidim (which have no direct link to the modern movement of Hasidism). They worked together in a successful revolt against both the assimilation into Hellenistic culture and oppression by Antioch’s rule.[1] The Temple was then rededicated to the service of God.

There is another miracle, however, that is an incredibly important aspect of the Hanukkah we know today. As recorded in the Talmud, there was almost no oil left in the Temple that had not been desecrated by the Greeks at the time of the rededication. The Temple had a menorah, and oil was needed for it as it was supposed to burn throughout every night. From the oil that was left, there was only enough to burn for one day, yet, incredibly, it burned for eight days, enough time to prepare new oil under conditions of ritual purity.

This miracle is the explanation for celebrating Hanukkah for eight days, as well as the reason for lighting the hanukkiah every night. It is best to place the hanukkiah in a place that it can be seen, such as near a window, as to show the miracle of Hanukkah. Hanukkah itself is not mentioned in religious scripture – the story can be found in the Books of Maccabees.

How is Hanukkah celebrated?

During Hanukkah, there is a minimum obligation to have one candle burning every night, and the candle(s) must burn for at least half an hour after night has fallen. As the days of Hanukkah go by, though, we light candles corresponding to each day of Hanukkah that has passed. It is a positive mitzvah (commandment) to light the Hanukkah candles, and families come together to enjoy this wonderful moment daily when the light of the hanukkiah graces and beautifies their home.

Each day of Hanukkah, after nightfall, the candles are lit with special Hebrew blessings, after which the popular hymn ‘Maoz Tzur’ – which describes about the glory of God – is sung. It is then customary that women refrain from labor such as laundry, household chores, or professional jobs while the candles are lit. If they stay lit for hours, this doesn’t mean they cannot work, rather, it is the custom that women refrain from work for half an hour after nightfall.

During Hanukkah, it is customary to enjoy oily foods, as the miracle of Hanukkah involved oil. Even since the Middle Ages, it is said that doughnuts (sufganiyot) have been a staple during Hanukkah. Ashkenazim enjoy the classic latkes, which are potato pancakes. It is customary to eat dairy foods on Hanukkah, as to recall how Yehudit bravely served cheese and wine to the Assyrian general Holofernes before beheading him during the siege of Bethulia.

Lighting the candles

Lighting the Hanukkah candles is so important that even a poor man who lives on the charity of others must either sell belongings or collect and save money in order to follow the custom. Each household member should preferably light their own candles, and the best method is to add an additional light every night of Hanukkah, meaning the first night one, the last night eight.

If using oil, olive oil is considered the best option. It is important that the flame will burn well and will also look beautiful. Wax candles can also be used and are a popular choice today.

On the hanukkiah, there is an extra place for the candle that is referred to as the ‘shammash’ (attendant). This candle is used to light the Hanukkah candles each night, as it is forbidden to derive any benefit from the Hanukkah candles themselves, preserving the sanctity of the mitzvah lights. The shammash should be lit in a way that it is evident it is separate from the rest of the Hanukkah candles, and there should be a shammash for each hanukkiah, not one for all the sets together.

Footnote:

[1] Hanukkah, Jewish Virtual Library, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/hannukah, access 26.11.2021.