- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

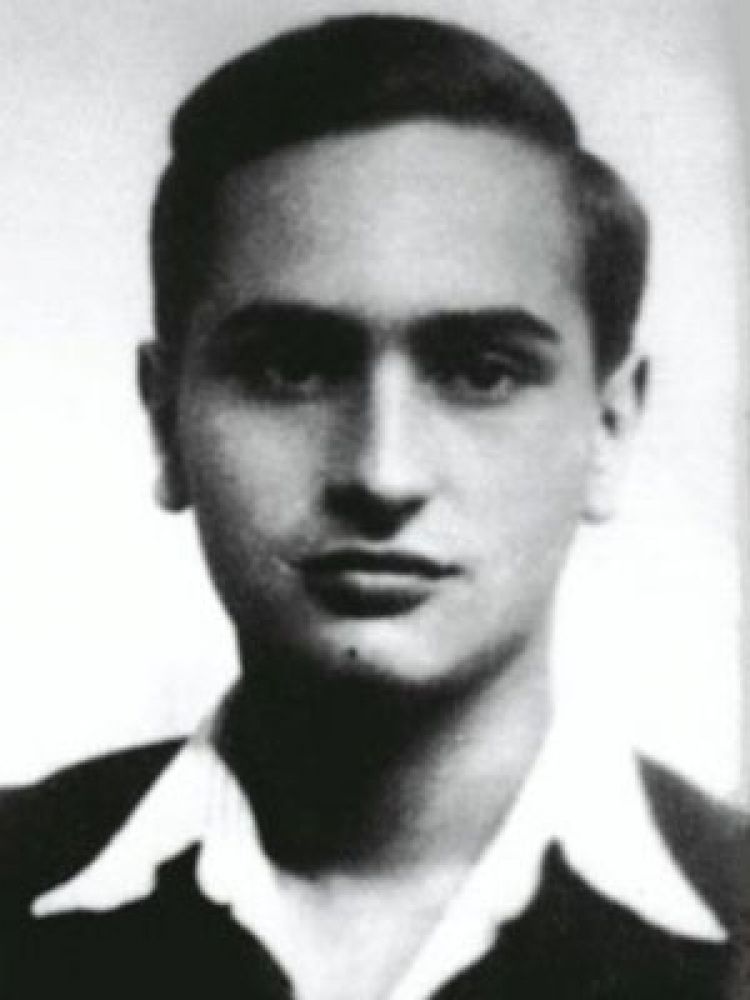

Szmul (Szmuel) Bresław was born on 20 March 1920 in Moscow. He came from an intelligentsia family who cultivated Zionist traditions. His father, Lippa (? -1942), was a Belarusian from Shklow; his mother, Rachel Roza, nee Ludwinowska (1880–1942), came from Kaunas, Lithuania. Szmuel was the youngest of four siblings. [1]

In 1925, his family moved to Warsaw and Szmuel began his education at the renowned Chinuch gymnasium, teaching in Polish and Hebrew. At the age of 11, he joined Hashomer Hatzair and became deeply involved with the movement. He soon became the leader of the Warsaw unit at 50 Długa street and a member of the editorial staff of the „Młody Czyn” („Youth Action”) periodical.

After graduating from the gymnasium, Szmuel intended to study at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Warsaw, and later – to move to Palestine, following the steps of his brother Fima Bresław, who emigrated in 1935. The war forced him to change his plans.

When the war broke out, he left Warsaw and reached Vilnius. He took the flag of Hashomer Hatzair with him, planning to take it to Palestine. He kept the flag with him at all times, and during his illness, he was storing it in a metal box in Kovel, recalled his Hashomer Hatzair colleague Hadelsman after the war. [2] From Vilnius, he was sent to Vilkomir, from where he wrote a letter to Palestine: I have walked 550 kilometres, under a hailstorm of bombs, through burning cities, hungry and wounded. On my way, the Germans took away everything I had with me. I was in the hospital in Rivne, they were operating my leg. Leaving the peaceful area of the Soviet Union after all of this required of me a lot of moral strength and conscious self-discipline. I made it. I am certain that I will make it to Palestine. This faith helps me to maintain balance and not to cry over everything I have lost in Warsaw. [3]

In February 1940, at the order of his organization, he returned to Warsaw with his friend and colleague Józef Kapłan. As the member of the High Command of the organization, he dedicated himself to educational work.

![bresław_1.jpg [63.09 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/7/29/6ef82d562b0e1131f575c0145ebeaf23/jpg/jhi/preview/bresław_1.jpg)

In late 1940 and early 1941, he was working on reinforcing the structures of Hashomer Hatzair in Radom (organizing units). In one of the letters, he was writing: I don’t care about difficulties. I believe that it is all my sacred duty. I was brought up in the spirit of the Hashomer Hatzair movement, which has always been an avant-garde of our HeHalutz youth, so in these days, I have to be where they need help and advice. Difficult Warsaw Ghetto days are coming. [4]

In early 1941, he found himself in the capital again. In the Warsaw Ghetto, he was one of the leaders of Hashomer Hatzair and an editor of periodicals (mostly in Polish) published by the organization (such as the „Neged Hazerem” weekly). He was also nominated to become a member of the School Organization Committee, belonging to the Jewish Social Care Society. One of his colleagues remembered him: From an early age, he was different from the rest of the boys from our kvutza. A mild look and the right approach to all things, his simplicity and magnanimity gained him respect among all friends. I keep in my memory his engaging stories and Szmuel himself, who had the best influence on people, encouraging them to put their work and effort into the movement. He was more intelligent than others, but this didn’t make him any less accessible or any more difficult to understand for other members of his kvutza. [5]

![bresław_2.jpg [145.67 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/7/29/53f4240941d61473b7526c5ba569c166/jpg/jhi/preview/bresław_2.jpg)

Bresław was also an enthusiast and expert on classical music. After the war, F. Grynsztejn wrote: We were surprise that Szmuel never sang together with us. He claimed that he couldn’t sing, that he had no voice. Despite this, he was studying Beethoven, Mozart and Wagner thoroughly. He was trying to encourage an interest in music among us. On Fridays, he was organizing meetings dedicated to music, gave lectures about various composers and their work, illustrating it with records (…) His extraordinary intellect, skill and knowledge stood out. There was no cultural event he wouldn’t attend. His lectures were very informative. He was often publishing brochures, serious and humorous, whose he was the sole editor. [6]

Until mid-July 1942, he was thoroughly monitoring international radio stations together with Mordechaj Anielewicz, later to become the leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. They were sharing the information about situation outside Poland (in Western Europe, the US, on the Eastern front) in a bulletin.

Cukierman recalled after the war that Mordechaj Anielewicz and Szmuel Bresław were young people whose sharpness of thought and language stood out. Both of them were young thinkers from the Warsaw group, sharing a particular ideological concept. [7]

Cooperation with Oneg Shabbat

In 1942 Szmuel Bresław and his colleague Józef Kapłan were invited by Emanuel Ringelblum to cooperate with Oneg Shabbat. Bresław contributed a few writings to the Archive, such as an interview with Irena Adamowicz about Polish-Jewish relations, Henryk Gotland’s biography (a sketch about a young man who could adjust to the conditions of the war), a study – „The housing officer” about the misuse of food stamps distribution and one report, „The disinfection column”, based on an account from a member of such a column.

A large collection of bulletins from radio monitoring held by Hashomer Hatzair was preserved in the Archive. Bresław wrote down several dozen of them. 26 June was particularly important for Oneg Shabbat – it was the day when the BBC broadcast a programme about the situation of the Polish Jews under German occupation, at 5 PM.

![bresław_3.jpg [119.01 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/7/29/afc42f391e6917888a1b82425ffbf13b/jpg/jhi/preview/bresław_3.jpg)

On 26 June, Szmuel, deeply moved, monitored the programme from London about the martyrdom of the Polish Jews. It was one of the most beautiful days in the history of the station. [8]

Especially for Oneg Shabbat, in mid-July 1942 Szmuel prepared a material – „The history or the radio monitoring station in the ghetto”, dedicated to the organization and functioning of this secret unit.

Szmuel Bresław joined the cause of building combat structures in the ghetto. When news about deportations began to arrive from Lublin, he organized a self-defence unit among his colleagues. They were carrying knives and brass knuckles. Together with Józef Kapłan, they were present at the founding assembly of the Jewish Combat Organization on 28 July 1942, representing Hashomer Hatzair. He became a member of the JCO staff.

During the first days of the deportations, when it was apparent that transports were being sent to Treblinka, a HeHalutz meeting was held with Cywia Lubetkin, Icchak Zuckerman, Józef Kaplan and Szmuel Breslaw. Resistance was discussed there for the first time (…) Szmuel Breslaw believed that we should attack German guards with knives, metal bars, daggers and whatever one could find, take a crowd of people along, and rush to the aryan side. [9]

On 3 September 1942, having heard about Józef Kapłan being arrested, Bresław took one of the switchblades and together with his colleague went to Gęsia street to find out where his friend was being held. It was a fairly peaceful day in the ghetto. Suddenly, they noticed a car full of Germans in the distance. They tried to run away towards one of the yards. The Germans chased them, caught both and battered them. When they found a knife in Szmuel’s pocket, they beat him to death. It was the cursed day, 3rd September – they day they murdered Szmuel Bresław and arrested Jozef Kapłan. [10] According to a different version of events, Szmuel wielded a knife against an armed German sat in a car. Bresław’s funeral was held on the next day, at the cemetery at Okopowa street. His grave didn’t survive. Years later, Grynsztejn, his colleague from Hashomer Hatzair, wrote that Szmuel was leading the resistance until the last minute of his life. [11]

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

![bresław_4.jpg [122.86 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/7/29/d9845d58becfdb44c8b90782eb34acb3/jpg/jhi/preview/bresław_4.jpg)

Footnotes:

The title: Emanuel Ringelblum about Szmuel Bresław [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, tom.29, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, p. 388 / The Ringelblum Archive, vol. 29, Emanuel Ringelblum’s writings from the ghetto, p.388.

[1] Fima Bresław (1913-2000) was one of the founders of the Amir kibbutz in northern Israel. His children and grandchildren are still living there. His second brother Józef Bresław (1904–1969) settled in Toulouse and built a clothing factory. Sister Dinah (1909–1942) was living in Warsaw with their parents. Together with members of the Ludwinowski and Cetlin families, they were resettled to the ghetto and murdered in Treblinka.

[2] P. Handelsman, Ze Szmuelem w jednej drużynie, Mosty/Zew Młodych, 4/1947, p. 32.

[3] F. Grynsztejn, Szmuel Bresław, Zew Młodych: słowo młodzieży szomrowej, 3/1946, p. 11.

[4] P. Handelsman, Ze Szmuelem w jednej drużynie, op. cit.

[5] Ibidem.

[6] F. Grynsztejn, Szmuel Bresław, Zew Młodych: słowo młodzieży szomrowej, 3/1946.

[7] Icchak Cukierman „Antek”, Nadmiar pamięci (siedem owych lat). Wspomnienia 1939–1946, scientific editing and foreword by M. Turski, afterword by W. Bartoszewski, Wyd. Naukowe PWN, Warsaw 2000, p. 63-64.

[8] Szmuel Bresław, Dzieje stacji nasłuchu radiowego w getcie, Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 22, p. 7.

[9] Hela Rureisen-Schupper, Pożegnanie Miłej 18, „Beseder”, Kraków 1996, p. 37.

[10] Icchak Cukierman „Antek”, Nadmiar pamięci, op. cit., p. 149.

[11] F. Grynsztejn, Szmuel Bresław, op. cit.

Bibliography:

Karine Breslaw, Un collaborateur de l’oneg shabbat parmi d’autres: Shmuel Breslaw (1920-1942), 20.04.2013, http://www.crif.org/fr/actualites/un-collaborateur-de-l%E2%80%99oneg-shabbat-parmi-d%E2%80%99autres-shmuel-breslaw-1920-1942/36492

Icchak Cukierman „Antek”, Nadmiar pamięci (siedem owych lat). Wspomnienia 1939–1946, , scientific editing and foreword by M. Turski, afterword by W. Bartoszewski, Wyd. Naukowe PWN, Warsaw 2000.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Hela Rureisen-Schupper, Pożegnanie Miłej 18, „Beseder”, Kraków 1996.

The Ringelblum Archive, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, ed. Katarzyna Person, vol. 5, JHI, Warsaw 2011.

The Ringelblum Archive, Prasa getta warszawskiego: wiadomości z nasłuchu radiowego, ed. Maria Ferenc Piotrowska, Franciszek Zakrzewski, vol. 22, JHI, Warsaw 2016.

The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, vol. 29, JHI, Warsaw 2018.