- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

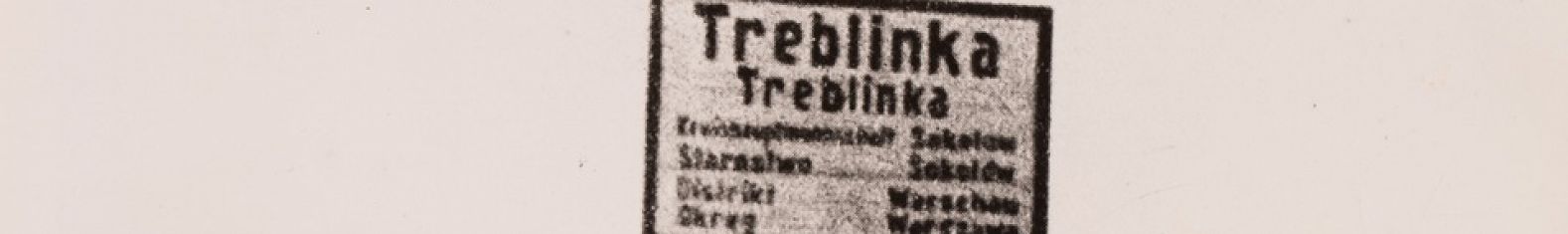

Officially, the Germans were carrying out ‘displacement’ to forced labor in the East. The Jews who were being ‘displaced’ from Warsaw received bread and marmalade. Although rumors of the Treblinka extermination camp had already reached the city, and the Oyneg Shabbes group had known about similar death camps in Chełmno nad Nerem (Kulmhof) and Bełżec for several months, and although it was quickly noticed that the trains departing from the city returned to it strangely quickly, too quickly so that they could reach some distant places in the East during this time, many starved, terrorized and despairing Jews continued to go to the Umschlagplatz.

Marek Edelman remembered:

‘It was the Umschlagplatz.

I stood and watched the crowds go by. People were driven along Zamenhofa Street and the columns entered Stawki almost directly to the Umschlagplatz gate. Now only the names remain, the street layout is completely different. I remember when I was in elementary school, Esperantists fought that Zamenhof was named after a fragment of Dzika Street that started, as it is today, at the back of the Mostowski Palace in Nowolipki but running slightly sloping to Stawki Street. (…) There were large four or five-story multi-yard tenement houses. They protruded over the houses of Niska Street and could be seen in Stawki Street from the gate leading to Umschlagplatz.

And on the stool, in the middle of the entrance gate, an SS man stood shooting. He shot at the windows of the house opposite, on Muranowska Street. When he saw a head or shadow moving, he shot at that window. Because from there people looked for their loved ones in the crowded crowd. Did people die there? It’s hard to say, but it was the atmosphere. Death.

It was the Umschlagplatz.

If you could, you had to get someone out of there. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t...

It was known that if you fall in here, if you don’t get out of the hospital window, if you don’t have family or friends in the hospital, you have no chance to save yourself. It happened that when some nurses were caught, their friends quickly threw their nurses’ uniforms through the windows and they entered the hospital through the ground floor windows, because there was a hospital in the Umschlagplatz, also doomed. Theoretically, there was still an infirmary there. In this infirmary, daughters broke their mothers’ legs and the ambulance took them away as sick. This absurdity, which the Germans introduced that you go to work – because you don’t take the sick with a broken leg, and they still gave bread for the way – deceived people. Some believed that they were actually going to work. Most, however, cried. You should have seen their faces. These children are led by the hand.’[1]

Emanuel Ringelblum, who, as a member of the Jewish Social Self-Help, was somewhat more secure against deportation, went to the Umschlagplatz to get a few friends out of there, including Dr. Icchak Lipowski:

‘I wanted to get to the Umschlagplatz at all costs in order to personally intervene on the spot regarding a few people who were taken to the Umschlagplatz. I put on a white band with the inscription «Umsiedlungsaktion»[2] and together with a group of Self-Help employees, laden with bread, I entered the Umschlagplatz. In a large square, fenced in with barbed wire, I saw a huge crowd pushing hard for the exit. Near the wires, I saw a weak Dr. Lipowski and his only daughter. I turned to the commander of the Umschlagplatz, a Jewish police officer Szmerling[3] (The Germans called him a Jewish executioner, and the Jews, due to his resemblance to the Italian marshal, «Balbo»). Then I intervened with him in the case of three people: in the case of Dr. Lipowski, the famous pianist Hanna Diksztajn and the famous painter Regina Mundlak. Szmerling promised to release these people and made an appointment with me to come to him in 3 hours. The second time I came back a few hours later, the situation was very different. Szmerling, the executioner of Warsaw Jews, had one of his fits of madness, he didn’t want to hear anything about any artists or scientists. When I started demanding vigorously, he took out his whip and started threatening me that I would go to Treblinka as well. The end was that Dr. Lipowski went to Treblinka.’[4]

Jankiel Wiernik, one of the few survivors of Treblinka, recalled how he was deported on August 23:

‘Next came the command to entrain. As many as 80 personas were crowded into each car with no way to escape. I was dressed in my only pair of trousers, a shirt and a pair of low shoes. I had left a packed knapsack and a pair of high boots at home, which I had prepared because of rumors that we were to be taken to the Ukraine and put to work there. Our train was shunted from one track of the yard to another. In the meantime our Ukrainian guards were having a good time. Their shouts and merry laughter were clearly audible.

The air in the cars was becoming stiflingly hot and oppressive, and stark and hopeless despair descended on us like a pall. I saw all of my companions in misery, but my mind was still unable to grasp the immensity of our misfortune. I knew suffering, brutal treatment and hunger, but I still did not realize that the hangman’s merciless arm was threatening all of us, our children, our very existence.

Amidst untold torture, we finally reached Malkinia, where our train remained for the night. The Ukrainian guards came into our car and demanded our valuables. Everyone who had any surrendered them just to gain a little longer lease on life. Unfortunately, I had nothing of value because I had left my home unexpectedly and because I had been unemployed, gradually selling all the valuables I possessed to keep going.

In the morning our train got under way again. We saw a train passing by filled with disheveled, half-naked, starved people. They spoke to us, but we couldn’t understand what they were saying.

As the day was hot and sultry, we suffered greatly from thirst. Looking out of the window, I saw peasants peddling bottles of water at 100 zlotys a piece. I had but 10 zlotys on me in silver, with Marshal Pilsudski’s effigy on them, which I treasured as souvenirs. And so, I had to forego the water. Others, however, bought it and bread too, at the price of 500 zlotys for one kilogram of rye bread.

Until noon I suffered greatly from thirst. Then a German, who subsequently became the „Hauptsturmfuehrer,” entered our car and picked out ten men to bring water for us all. At last I was able to quench my thirst to some extent. An order came to remove the dead bodies. If there were any, but there were none.

At 4 P.M. the train got under way again and, within a few minutes, we came into the Treblinka Camp. Only on arriving there did the horrible truth dawn on us.’[5]

The shocked Ringelblum noted on October 15, 1942, a month after the great deportation ended:

‘Why? Why was there no opposition when they began deporting 300,000 Jews from Warsaw? Why did they let themselves be led like sheep to the slaughter? Why did it come so easily, so smoothly for the enemy? Why didn’t the torturers suffer a single victim? Why 50 SS men (others say even less) with the help of a unit of 200 Ukrainians and as many Latvians could do it so smoothly?’[6]

In retrospect, the organizer of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto emphasized the importance of hunger for the effectiveness of deportation and the fact that the Jewish Council supported the German propaganda about the ‘relocations’ of Jews. ‘He compared the German extermination program to a well-planned and well-executed military campaign based on surprise, deception, overwhelming power, and speed’ – writes Samuel D. Kassow. – ‘the Germans also exploited the admirable wish to protect the weak and vulnerable, so that people accompanied children and parents to their deaths, even at the cost of their own lives.’[7].

![logos_TaubePhilanthropies.png [7.41 KB]](/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/11/f10aa2f8473e22e198a5258cd5f57e7d/png/jhi/preview/logos_TaubePhilanthropies.png)

The project is generously supported by the Taube Philanthropies.

Footnotes:

[1] Marek Edelman, Paula Sawicka, I była miłość w getcie, Warsaw 2009, p. 100–101.

[2] German for ‘resettlement action’.

[3] Mieczysław Szmerling, an officer of the Order Service, chairman of the Anti-Epidemic Company at the Health Department of the Jewish Council, commander of the Umschlagplatz.

[4] Archiwum Ringelbluma, v. 29a, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, edited by Eleonora Bergman, Tadeusz Epsztein, Magdalena Siek, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2018, p. 190. Some footnotes were omitted in this article.

[5] Jankiel Wiernik, Rok w Treblince. A Year in Treblinka, foreword by Władysław Bartoszewski, Rada Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa, Warsaw 2003, p. 49–50. Wiernik usually wrote the names of Germans and Ukrainians in lowercase. Typesetting errors preserved in the original have been corrected.

[6] Archiwum Ringelbluma, v. 29, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, edited by Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, translated by Adam Rutkowski and others, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2018, p. 392.

[7] Samuel D. Kassow, Who Will Write Our History? Rediscovering a Hidden Archive from the Warsaw Ghetto, Knopf, New York 2011, p. 351.