- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

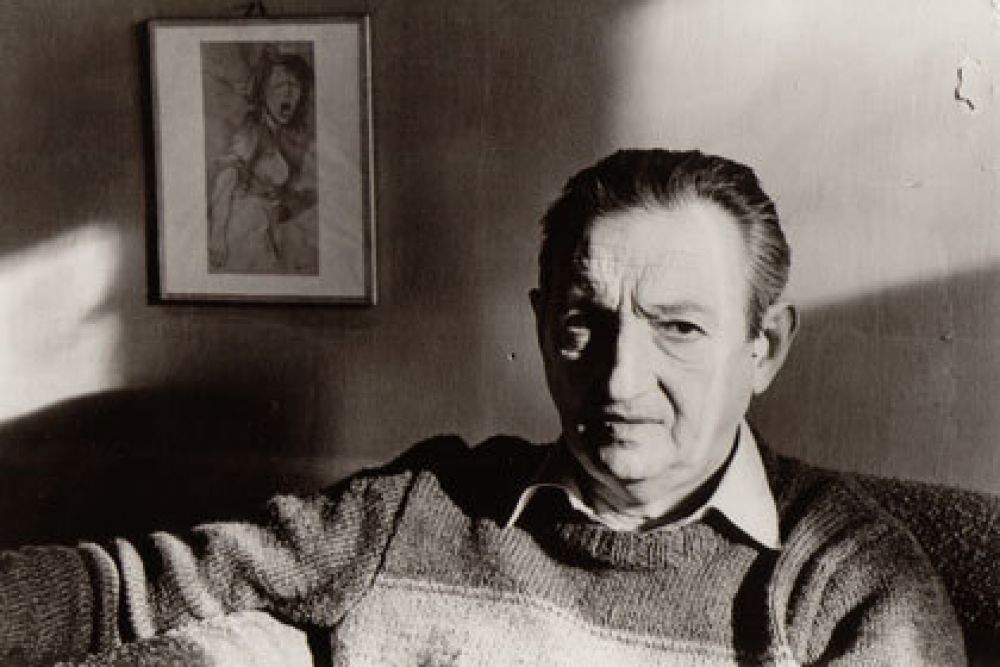

Marek Edelman /

‘August 1, 1944

We lived then with Antek and Celina [Icchak Cukierman and Cywia Lubetkin from the Jewish Combat Organization – ed.] at Leszno street, in a tenement house adjacent to the evangelical church[1]. It was one of the two apartments on the second floor in the second outbuilding. One of its rooms had an additional wall, professionally built by a bricklayer, behind which a hiding place was created. The apartment was hidden by Marysia Sawicka, who, together with her aunt, Anna Wąchalska, participated in organizing our life on the Aryan side. She hid the apartment, that is, she rented it in her name, and she came to us with food and messages. (…) On Wolska street, she saw German carts loaded with furniture, bundles and wounded soldiers going towards Łowicz. The mood in the city is strange, everyone is happy. Although rumor said that further mobilizations had been canceled, and theoretically none of us knew that the uprising was about to begin today, there was an excitement in the city.

And suddenly, around 5 p.m., we heard the patter of many feet on the stairs. We looked through a gap in the door and saw armed young people leave a neighboring flat one after another. We considered this neighbor dangerous all the time, and even feared her, believing that she was watching us, because every time our doors opened, she checked what was happening. However, with an arsenal at home, she could not be sure of anyone, which was undoubtedly why she surveyed us so suspiciously. Young people went to the yard, and we could see them gathering and putting on white and red bands on their sleeves. (…) After a short time, we heard shooting from afar. First, single shots, then denser sounds of shooting. So it is the uprising! We sat in the apartment without any news. The whole time we were tormented by the question – should we go out or not?’.[2]

The first person to arrive at their apartment was Aleksander Kamiński, editor-in-chief of the Polish Home Army’s Information Bulletin and author of Stones for the Rampart (Kamienie na szaniec). He warned them that they might be in danger from some insurgent units – on the same day his associate Jurek Grazberg died after he had been considered by some insurgent unit as a ‘provocateur’ because it was unusual to see an armed Jew in the city where the Germans murdered almost all Jewish residents.[3]

In the Warsaw Uprising, in the ranks of the People’s Army [Armia Ludowa], fought Marek Edelman, Icchak Cukierman, Cywia Lubetkin, Kazik Ratajzer (known after the war as Simcha Rotem), Jewish Combat Organization fighters from 1943. Thanks to ‘Antek’ Cukierman, who maintained contacts with both the Home Army and the People’s Army[4], a special JCO platoon under the command of Cukierman[5] was formed as part of the latter, composed exclusively of soldiers with Jewish background. The insurgent units were joined by Jews hiding in the city (it is estimated that there were from a few to several thousand Jews living in hiding[6]), Jews liberated on August 1 by the Home Army unit at Umschlagplatz, Polish, Greek, Slovak and Hungarian Jews released on August 5 by the Home Army from the camp at Gęsia street[7]. Jewish doctors (such as Alina Blady-Szwajger), liaison officers and nurses also participated in the uprising. Samuel Willenberg, a participant in the 1943 Treblinka uprising, fought in the ranks of the Home Army and the People’s Army.

Fights with Germans, such as the struggle for the strategically located ‘Red Building’ at Bugaj street in the Old Town, Edelman mentions typically laconically – as ‘skirmishes’[8], shootouts, placing explosives. The insurgents withdrew from the Old Town through the sewers to Żoliborz (fortunately, it was a ‘high comfortable sewer’[9] and the level of sewage was low). For the Jewish insurgents, it was the second time they descended under the streets during the war. The first time was in May 1943, when they left the burning ghetto and came out at Prosta street. The insurgents of 1944 were plagued by lice and hunger, and were threatened with bullets from German shooters aimed at openings in barricades and passages between the streets.

People of Jewish origin were sometimes not allowed to join insurgent units due to the lack of weapons or suspected cooperation with the USSR. [10] They also couldn’t feel quite safe. Edelman recalled that he was detained at Przejazd street[11] by an insurgent patrol, made up of very young soldiers, and was saved by their commander from being shot.[12] A similar incident happened to Julek Rutkowski (Fiszgrund), son of Salo Fiszgrund from the JCO, arrested by insurgent gendarmes under the suspicion that he was ‘a Jewish spy and saboteur because he illegally possesses a weapon’.[13] He was saved by Kazik Ratajzer.

After the collapse of the uprising, six members of the JCO unit of the People’s Army were hiding in a shelter in a house at Brodzińskiego 3 street in Żoliborz. 13 JCO fighters, including Edelman, Cukierman and Lubetkin, hid in the basement of the house at Promyka 43 street in the same district. Most of the first group managed to get out of the city on their own, the second was saved with the help of the Home Army, the People’s Army and the Polish Red Cross only in November 1944, after the Germans began to build a bunker in the same building.[14]

Edelman, reluctant to make an epic of the war, told Hanna Krall that during the ghetto uprising he did not see the difference between ‘running on the roofs’ and ‘sitting in the basement’. ‘But I saw the difference later, in the Warsaw Uprising, when everything was already happening during the day, in the sun, and there was no wall. We could attack the enemy, retreat and run. The Germans were shooting, but I was also shooting, I had my rifle, I had a white-and-red armband, there were other people with white-and-red armbands – many people around – listen, how wonderful, how comfortable this fight was!’.[15]

‘I had an insurgent uniform with a white-and-red armband and a gun, but it was my Jewish face that determined the attitude of the people I came into contact with. Some reacted well, some badly. Some were friendly, others unfriendly. What I wrote may be without much order and composition, but these are only shreds of my memory’[16] – recalled Edelman.

Bibliography:

Krzysztof Bielawski, Żydzi w powstaniu warszawskim, https://sztetl.org.pl/en/tradition-and-jewish-culture/history-of-the-jews-in-poland/jews-in-the-warsaw-uprising, Virtual Shtetl Portal

Marek Edelman, Paula Sawicka, I była miłość w getcie, Warsaw 2009.

Hanna Krall, Zdążyć przed Panem Bogiem, Cracow 1997.

Krzysztof Persak, Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB), https://sztetl.org.pl/en/glossary/jewish-combat-organisation-zob-zydowska-organizacja-bojowa, Virtual Shtetl Portal

Antoni Przygoński, Armia Ludowa w Powstaniu Warszawskim 1944, Warsaw 2008.

Footnotes:

[1] At the time, the adress was Leszno 18 street. Antoni Przygoński, Armia Ludowa w Powstaniu Warszawskim 1944, Warsaw 2008, p. 139.

[2] Marek Edelman, Paula Sawicka, I była miłość w getcie, Warsaw 2009, p. 125–127.

[3] Ibid., s. 127–128.

[4] M. Edelman, P. Sawicka, op. cit., p. 131.

[5] Krzysztof Persak, Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB), https://sztetl.org.pl/en/glossary/jewish-combat-organisation-zob-zydowska-organizacja-bojowa, Virtual Shtetl Portal

[6] Krzysztof Bielawski, Żydzi w powstaniu warszawskim, https://sztetl.org.pl/en/tradition-and-jewish-culture/history-of-the-jews-in-poland/jews-in-the-warsaw-uprising, Virtual Shtetl Portal

[7] A. Przygoński, op. cit., p. 48.

[8] M. Edelman, P. Sawicka, op. cit., p. 137.

[9] Ibid., p. 138.

[10] K. Bielawski, op. cit.

[11] The Przejazd street met with Leszno street more or less at the location of today’s Muranów Cinema (Kino Muranów).

[12] M. Edelman, P. Sawicka, op. cit., p. 134.

[13] Ibid., p. 131.

[14] A. Przygoński, op. cit., p. 102.

[15] Hanna Krall, Zdążyć przed Panem Bogiem, Cracow 1997, p. 67.

[16] M. Edelman, P. Sawicka, dz. cyt., s. 125.