- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

For the first few weeks of summer of 1941, the combat concentrated mostly on the pre-war Polish territories, which put Polish citizens, especially Jews, in danger. Until the end of 1941, the Germans had killed several dozen thousands of Poles and Belarusians as well as about half a million Jews. They had also created conditions in which Jews had been killed and persecuted by their Christian neighbours.

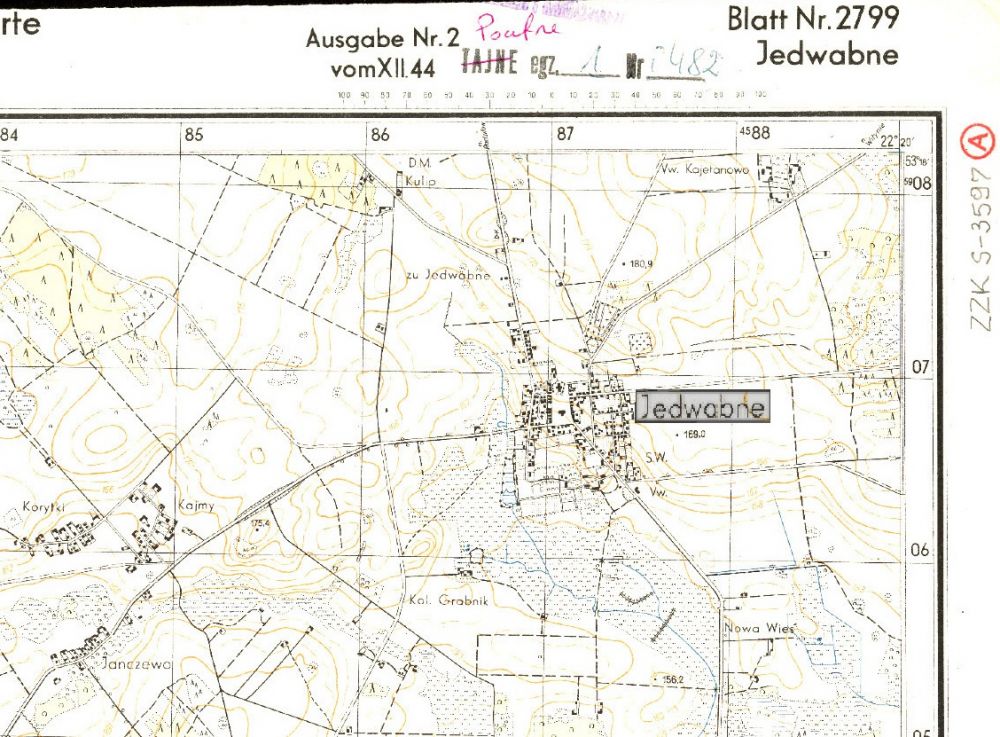

In Jedwabne, on 10 July 1941, the Poles had burned in a barn and murdered the entire local Jewish community – altogether about 1,000 people. Among many other acts of murder committed in the Białystok and Łomża region in the summer of 1941, this one stands out due to its scale, as well as because of the number of people put on trial after the war, found complicit in the killing of the Jews, or acquitted. The proof material mentions as many as 102 inhabitants of Jedwabne and nearby area who participated in the crime or were its direct witnesses.

The genesis of the Jedwabne crime is very complex. It has been a subject of studies by many historians, beginning with Jan T. Gross and his book Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, published in 2000. The image presented by Gross had been significantly expanded by Anna Bikont’s The Crime and the Silence: Confronting the Massacre of Jews in Wartime Jedwabne and two volumes of collected essays, Wokół Jedwabnego (On Jedwabne, edited by P. Machcewicz and K. Persak), published by Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance in 2002. Thanks to these works, we have received a credible profile of the group of people guilty of murdering the Jews in Jedwabne, following encouragement from German SS troops. These were ‘common people’, ordinary citizens of the town.

I have examined the context of the crime in Jedwabne and several dozen nearby towns and villages in my book U genezy (At the genesis). I have determined that until mid-July 1941, acts of murdering Jews by their Christian neighbors had taken place in 67 locations. In most cases, German police, Einsatzgruppen or Wehrmacht were joined by non-Jewish locals, mostly Poles. In 51 towns and villages, violence against Jews began before 4th of July – the day on which Einsatzkomaando unit moving from Warsaw, led by SS-Hauptsturmführer Wolfgang Birkner, arrived in Bialystok. Hostility among the locals, which had been increasing for the first two weeks of war, exploded with full force in the following week. A common factor was the presence of Einsatzgruppe B, a sub-unit of the Security Police in a particular town (four of these groups were following the Wehrmacht), or one of the special German units deployed to the East from the General Gouvernement, Ciechanów district or Tylża. Killings in Jedwabne and Radziłów were preceded by anti-Jewish unrest in other towns; they usually had similar course, scope and outcome. In certain cases, acts of violence were committed by a small group of ‘activists’, in other cases – by entire, or almost entire, communities.

The situation of Jews under two occupations

In testimonies submitted by the Jews during post-war trials, caused by the Polish Committee of National Liberation decree from August 1944 which declared punishment for traitors of the Polish nation, hostile treatment from Polish neighbors was mentioned more frequently than the planned, methodical murder carried out by the Germans. Most of them mentioned the most obvious, direct explanations for aggression, such as envy of property, leading directly to robbery, or a drive to humiliate neighbors who were richer before the war and usually coped well with the Soviet occupation.

It is difficult to estimate the number of victims in particular towns and villages, as well as the number of perpetrators. Nearly all the Jews who had submitted their testimonies and accounts mentioned mass participation of Polish locals in the killings. In cases when the names of perpetrators were actually estimated after the war, they were nearly always only members of Polish support police formations. In fact, the violence was more frequently committed by ordinary villagers, anonymous to the witnesses.

What led to the outbreak of hatred of Polish Christians towards their Jewish neighbors? The pre-war distance between them had extended significantly due to attitudes of a part of the Jewish community during the Soviet occupation, and Polish reactions to them. These include the Jews’ enthusiasm expressed towards the Red Army, which attacked Poland on 17 September 1939 and annexed the Eastern Borderlands. The feeling of threat didn’t provide convincing explanation: at the time, nobody expected that the German policy towards the Jews would lead to the Holocaust. Where did the enthusiasm come from then? To an extent, it was ‘an expression of difference, cutting oneself off the Polish state, which the Soviet Union was at war with, abandoning the responsibility for the Polish State’. It should be remembered that the Polish state gradually introduced an anti-Semitic policy in the 1930s.

If anti-Semitism hadn’t had intoxicated the soil before the war, new experiences wouldn’t have been so easily and commonly generalized. Another factor was that the source of negative opinions towards the Jews came from circles which had gone underground after the Soviet withdrawal. These groups included people who had certainly excelled at national awareness, activism and courage. In the Eastern Borderlands, Polish national symbolism had, for many centuries, referred to civilizational and cultural significance of Polish settlement: Polishness was a stronghold surrounded by a sea of barbarism. June 1941 provided a chance for long-awaited revenge for humiliation experienced during the Soviet occupation.

This opinion finds confirmation in reports from Polish resistance, which had been developing slower in the Eastern Borderlands than under the German occupation. A common opinion found in reports submitted by various groups was a belief that the Jewish community was favored by the Soviet authorities. We read that especially the Jewish ‘lower classes’ (the masses, the poor, the mob) posed danger towards Poland, while upper classes (plutocracy, intelligentsia, financial circles) mostly remained loyal to the Polish state.

The SS leaders were right in their expectations that a wave of hostility towards Jews would spread widely in former Polish, Lithuanian and Romanian territories. Anti-Jewish pogroms in the early weeks of the German-Russian war didn’t result only from German scheming, even though the presence of German soldiers and policemen facilitated their escalation. The pogroms were helpful for the Germans in carrying out their main plan – pacifying the occupied territory with fairly small effort.

In this light, we can interpret the orders given by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Main Security Office, on 29 June and 2 July 1941, according to which the Einsatzgruppen (operational groups of the Security Police and the Security Service) were supposed to carry out ‘cleansing actions’ and support ‘self-cleansing actions’ organized by local anti-Communist forces in the territories seized by the Wehrmacht. The attacks were aimed at people arbitrarily assumed to be the mainstay of the Soviet rule – commissioners and Jews ‘in important party and state positions’.

The goals of the Germans

Local pogroms became an important section of quickly developing extermination operations, leading to a complete eradication of the Jewish population. I would describe the first weeks of the German occupation as a period of chaotic terror. The Einsatzgruppen, moving from one town to another, were killing dozens of Jewish men, usually denounced by their Christian neighbors, as well as a small number of non-Jewish supporters of Soviet rule. German documents mentioned that ‘a cheerful mood’ accompanied the entry of the Wehrmacht, and the attitudes towards the new occupant oscillated from open enthusiasm in Lithuania and areas with Ukrainian population, to ‘friendly neutrality’ from the Poles.

While we have no grounds to claim that German soldiers had acted according to any instruction, we can notice a definite pattern in behaviors towards the Jews. Arrogance, willingness to humiliate victims, cruelty; all accounts mention descriptions of violence – like in Jedwabne, beating, cutting beards, forcing people to perform humiliating ‘gymnastics’. The soldiers were desecrating synagogues and prayer houses, destroying holy books or forcing the Jews, dressed in religious clothing, to destroy religious objects themselves. Sometimes, like in Bialystok and eight other nearby towns, they burned synagogues.

In June and July 1941, German rule in the area was based mainly on small, understaffed military police posts. German military units stayed for a shorter or longer period of time in almost every larger town (soon after 22 June, from 5 to 15 July or in late July and early August). The presence of police or army in that period always had an influence on the treatment of the Jewish population, but German repressions were of various scale.

The first repressions towards the Jews in the towns of Mazovia and Podlasie were directly linked to the movement of troops. On 24 June, one day after the arrival of the German troops, one of the Jedwabne defendants, Karol Bardoń, witnessed torturing three Poles and three Jews because of their former collaboration with the Soviet authorities. He noted that ‘these six bleeding men were surrounded by the Germans. If front of the Germans, there stood a few civilians with sticks thick like the ones used in horse carriages, and one German was calling them: «Don’t kill them immediately! Beat slowly, let them suffer». The beaten men were dropping their hands. I didn’t recognize these civilians who were beating because they were surrounded by many Germans’. He added that there were also many military cars in the square.

The planned, systematic proceedings of the German police were aimed at discovering and killing supporters of the former Soviet authorities, but the scale of their success depended on help from the Polish locals. It was assumed that supporters of Communism could be found mainly in the Jewish community. Usually, arrests were made according to proscription lists, prepared by the locals or by the police basing on denunciations.

On other occasions, great spectacles of fear were organized as a symbolic end of the Soviet rule, simultaneously blaming the Jews for the Soviet crimes. In only two towns, Radziłów and Jedwabne (7 and 10 July 1941), such a spectacle became a prelude to mass murder of local Jews. In Zaręby Kościelne and Siemiatycze, Poles alone had organized such events, but they didn’t develop into pogroms.

Motivations and organization of the perpetrators

We don’t know almost anything about the attitudes of Polish elites, aside from people who joined temporary local governments. Polish priests, according to Jewish sources, reacted in various ways to these dramatic events. In Grajewo, Jasionówka and Knyszyn, they tried to tone down moods, sometimes bravely defending the persecuted. In Radziłów and Jedwabne, they remained passive in the face of the Jewish tragedy.

Robbery as the motivation for pogrom was mentioned in practically every Jewish testimony. It was the simplest explanation for a sudden outbreak of aggression among neighbors, who often had known each other for years. But the Polish witnesses rarely mentioned the wealth of their Jewish neighbors.

Another element repeating in the accounts is a recollection of exceptional, extreme cruelty – women were raped and killed, men and children were stabbed to death with knives, pitchforks, axes, hatchets. There were no acts of compassion, at best only shameful turning heads. There is no surprise that testimonies mentioned such terms as: barbarians, hooligans, bandits.

In modern times, even during periods of chaos and anarchy, pogroms of Jews were taking place in locations in which locals were under an extended influence of nationalist groups. Ideologies propagated by these parties included definitions of ‘enemies of the community’, whose qualities were defined as directly opposite of the group’s own positive characteristics. It seems that at least since the 1930s, also a large part of people in the Łomża region and Podlasie considered Jews as their worst enemies. It was not an exceptional case in Central and Eastern Europe.

We should also emphasize, after Dariusz Stola[1], that the mass murder in Jedwabne was possible mainly thanks to efficient organization of its perpetrators, led by the self-proclaimed mayor Marian Karolak and his closest associates. It involved assigning roles to the participants of the complex effort consisting of several stages: gathering the Jews in one place, immobilizing them, removing any prospects for help, preventing escape, initial elimination of anyone capable of resistance, and eventually – leading the Jews to the barn and burning them do death. It certainly wasn’t Karolak who decided who was responsible for what kind of ‘work’. I believe that the murderers recruited themselves from those willing to murder; those reluctant to kill, but still eager to participate, were preventing the Jews from escaping. Passive witnesses were the largest group – they set up a tight cordon around the victims, so horrible, because it removed all possibility of help. Certain men from the last group were certainly pressured by activists and over a dozen members of German military police present in town. Yet without the specific, voluntary division of work, killing many hundreds of people (the number is victims is estimated between 600 and 1000) wouldn’t be possible. We know that the small number of Germans in Jedwabne, as well as in Radziłów, didn’t open gunfire, neither did they burn down houses. Their mere presence was sufficient.

Proper organization allowed a certain number of men in Jedwabne – between several dozen and one hundred – to collaborate despite no prior experience in police or the military. In majority of cases, they didn’t recruit from the social margins. The ‘division of work’, social base and motivations of murderers were similar in Radziłów; there, an excuse which allowed the perpetrators to overcome initial reluctance, was more distinct. According to a testimony from Henryk Dziekoński (accused of participation in the pogrom), the SS men who arrived in town told the civic guards that local Jews were responsible for deportations of a large number of Poles to Siberia. Now, there appeared an opportunity for revenge. The locals believed that they could kill all the Jews.

Such an approach helps understand how it happened that in Radziłów all the Jews were murdered, but it doesn’t provide an answer to a more important question: why it happened. In order to understand such murders as the ones in Radziłów and Jedwabne, it’s not enough to emphasize the sources of Polish-Jewish antagonism and to reconstruct the situational context in which increasing acts of aggression were reaching a critical point in which they developed into a ‘cacophony’ of murder. Radziłów and Jedwabne remain not fully explained without an analysis of the last ‘classic’ pogrom of Jews in Wąsosz, located 30 kilometers away, at night of the 4th and 5th July. A fairly small number of killers had killed in darkness, in an extremely barbaric way, using axes and iron bars, several dozen of local Jews, regardless of age and gender. On 6 July, the Wąsosz murderers arrived in Radziłów, as an already formed unit of civic guard, ready for next acts of murder, rape and robbery. Locals didn’t let them kill ‘their’ Jews – not in order to save them, but to kill them in their own, new way, and to seize their belongings.

The Wąsosz pogrom seems much more typical for summer of 1941 than the crimes in Radziłów and Jedwabne, shocking with their organizational ‘innovation’. In dozens, maybe hundreds of Wąsosz-like towns, a ‘social process which turns individual motivations into collective action’ was taking place. During that process, society – demoralized after two years of Soviet occupation – was reorganizing, not in order to resist strong Germans, but to kill defenseless Jews.

Footnote:

[1] D. Stola, Pomnik ze słów, „Rzeczpospolita”, 1–2 June 2001.