- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

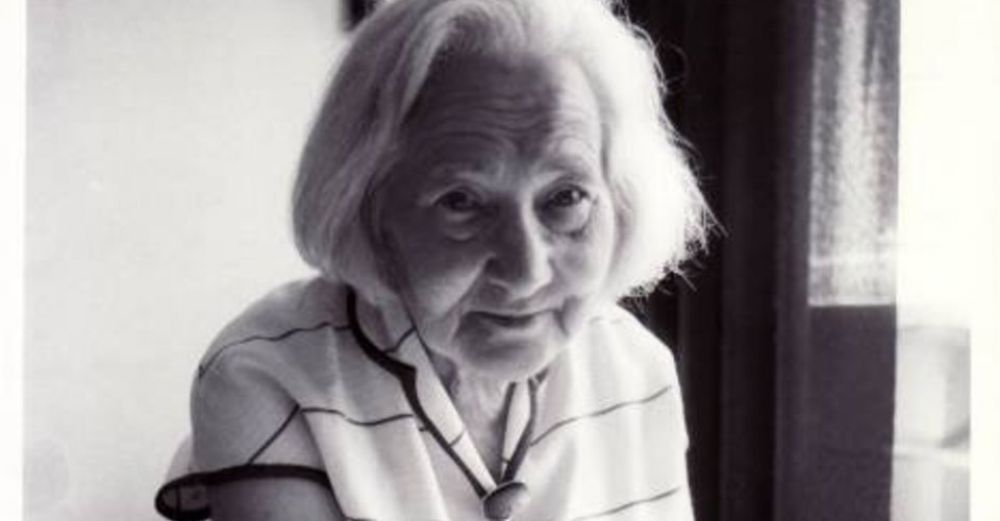

Adina Blady-Szwajger

Marek Edelman wrote about her: As a doctor and a human being she lived through the annihilation of the Warsaw Ghetto, she lived through the annihilation of its children. She led common life with her little patients and witnessed their death. Unlike many others she was there by every single dying child and she was dying with time after time. Adina Blady-Szwajger worked in the Bersons and Baumans Hospital from 11th of March, 1940. She survived liquidation of the ghetto and from 25th of Janurary, 1943, she was hiding in Aryan part of Warsaw where she became courier for Jewish Fighting Organization. Her book I Remember Nothing More is the most dramatic and shocking record of experiences of the doctor working in the Warsaw Ghetto.

In September 1939 she was a student of the XVI trimester of medicine studies at the Medical University and in academic year of 1939/40 was supposed to graduate and be granted the right to practice medicine. From the beginning of the war she engaged in helping the sick – together with a nurse, neighbor from Świętojerska 30, they arranged “dressing station” in which she stayed without a break during three week long siege of Warsaw. She dreamt of pediatrics, thus even prior to establishing of the ghetto she reached out to the Bersons and Baumans hospital and its chief physician Anna Braude-Hellerowa, what she later recalled: Chief physician impersonated every dream and phantasies of a young pediatrician. She was well known and respected doctor, great organizer and community worker. Moreover, what was not indifferent to a young girl having her head in the clouds, she was a romantic.

Young doctor landed in the internal ward as and aide to doctor Helena (Hela) Keilson when, as she recalls (…) it was still normal, real ward. With glass walls so that the nurse could see what was happening, with white beds by the white walls and almost normal children with regular sicknesses. It was still before closing of the ghetto and children were going through regular children diseases. The hospital staff got really close to each other during the first lock down when alleged in-house infection with typhus was detected. It was when Adina Blady-Szwajger befriended sisters Keilson: Hela – the doctor and Dola, the head nurse of the hospital; Tosia Goliborska – manager of the laboratory and lab technician Fecia Fesztówna, as well as Marek Edelman, the hospitak courier at that time. They were having breakfasts together during which they always had a shot of spirit. This one shot didn’t make us tipsy, but helped us work. And later, during the severe famine, we found out what calorific value this one shot had. Nobody from our group had swelling caused by hunger. 200 extra calories had, without any doubt, weighed a lot.

From spring of 1940 rumors on establishing closed Jewish district became more frequent. In his diary Emanuel Ringelblum described the day of closing the ghetto: The day when the ghetto was established, Saturday, 16th of November, was horrible. People hadn’t yet known that the ghetto will be closed, so this message struck as a bolt from the blue. On every junction there were the checkpoints of German, Polish and Jewish policemen who were controlling those authorized to pass.

In this period the number od childred suffering from TB, from which, at that time, children didn’t recover. Nonetheless, the hospital staff maintained high standard of care.

Adina Blady-Szwajger remembered: Treatments in the morning, blood tests, ward rounds, writing doctors’ orders, and later on filling in medical histories so that the documents could be preserved for years. For a moment you couldn’t think that these documents will be useless for anyone – just like you couldn’t think that you could neglect sick child. Just like before the war difficult cases were discussed, histories of presenting complaints were read and just like before the doctors had to explain every death and prove that they did everything they could to keep patient alive. Especially one death shook Adina really hard. It was a 13-year-old Ariel. On this day, my 24th birthday, I received unusual in the ghetto gift: three fresh daffodils. Ariel laid in the hospital morgue. I went to him I put those three flowers next to him. I had nothing more to give. My hands were empty and I couldn’t find words of farewell to the kid who should have lived. (…) On the next day, we discussed Ariel’s death at the briefing. But we didn’t have to explain it anymore. Everybody realized that we are less capable of saving lives and are becoming providers of silent death.

Hunger was the common experience for the Jews locked in the ghetto. It wasn’t same for everyone, but it was most severely felt by the poorest, displaced persons and orphans. Due to drastically insufficient food rations set for the ghetto by Germans, everyday existence revolved around feeling hunger and thinking up ways to get food. In her memories Adina Blady-Szwajger describes a scene from Leszno street when starving boy, so called “grabber” pulled a bunch of violets from her hand and ate them. This is how Lejb Goldin writes in “The Chronicle of One Day” about this indescribable physical and mental condition: Yesterday’s soup and today’s soup are separated but nothing less than eternity. I can’t imagine that I could live one more day like that, with such hunger gripping my throat.

In November 1941 the research group was formed, which starting from February 1942 was describing from scientific perspective famine sickness and its influence on human body. Although the doctors also experienced hunger they perceived clinical research as manifestation of spiritual and intellectual resistance. Adina Blady-Szwajger remembers: Not only did the doctors in the ghetto not ceased to be doctors, but to the very last moment they kept working scientifically thinking about those who will come after them. The last meeting of this group was held in August 1942, during the action. Doctor Milejkowski informed those who gathered that this was their last session and told them where their report will be hidden. In the cemetery, among other locations. A week after this meeting almost all of the participants were dead.

However, the biggest threat to the ghetto was epidemic of typhoid fever, which even rich, doctors and our heroine could not avoid. Renowned bacteriologist and epidemiologist, professor Ludwik Hirszfeld, didn’t have any doubt that the epidemic was a result of restrictions imposed on the ghetto by Germans and their ineffective policy which led to creating new Typhoid Marys. When you cram one district with 400,000 tatterdemalions, take everything away from them and give them nothing, then you create typhus – Hirszfeld, who was in the ghetto until the end of February 1941, wrote in The Story of One Life. Adina Blady-Szwajger contracted typhus when she went to Displaced Persons point to make an injection to a hospital porter suffering from swellings caused by hunger. When I left it turned out I “sat” in the nest of lice. They were all over my blue dress with black stripes (…) – she remembered.

From the beginning of the liquidation of the ghetto Adina Blady-Szwajger saw thousands of Jews off to Umschlagplatz as they marched under the hospital windows on the corner of Leszno i Żelazna Streets towards Stawki Street. This is how she remembered on the first days of the liquidation: So walked by doctor Efros with her newborn son in her hand and doctor Lichtenbaum with her mouth wide open like she was screaming. And so they kept walking and walkin, with baby carriages and some weird stuff, some hats and coats, pots and bowls, and the kept walking…

Chief physicians and heads of hospital wards had to face one more tragic experience, when they had to decide who to give “numbers of life” – designating who is “useful” and can remain in the ghetto. Family? Hospital staff? Doctors or nurses? Experienced or young? Many desperate conversations and decisions had to be made, some of which resulted in giving dear ones lethal doses of morphine. Injections helped many to avoid being shot in hospital bed by Germans and Lithuanians, murderous march to Umschlagplatz or death in the gas chamber. In her memoirs Adina Blady-Szwajger describes the moment of giving poison to kids: Then I went upstairs. Doctor Margolis was already there. We grabbed a teaspoon and went to infants’ room. And just like for the last two years of real work in the hospital I was leaning over the beds, now I was pouring in those little mouths their last medication. Only doctor Margolis was there with me. And there were screams coming from the downstairs, because Lithuanians and Germans were already there and were taking the sick from their room to train cars. Then we went to older children and I told them it was medicine so that it won’t hurt them. They believed me and drank from the cup as much as they were told. Then I told them to undress, lay in bed and have a nap. They obeyed and laid down. After several minutes, I don’t remember how many, when I returned to the room they were already asleep. And I don’t know what happened next.

Years passed. Many years. (…) There is not even one burnt house from windows of which mothers were throwing children and followed them jumping after them. (…) So sometimes I walk this modern district’s cobblestones which cover the bones of those burnt, look at this spot in the sky where my house and other houses once stood.

This is how Adina Blady-Szwajger ends part of her book mentioning names of the staff members who were murdered in the ghetto, in Umschlagplatz, in Treblinka, Otwock, Majdanek, who died on typhus, TB, famine sickness, gave the number of life to their dear ones, committed suicide. From 36 people whose name we know only 17 survived. Remaining 150 people – doctors, nurses, hospital porters, whose names remained unknown to the author, died in unidentified circumstances.