- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Sz. Szajnkinder (Szejnkinder) was playing as a midfielder and captain of the Hagibor (Hebrew for „hero”) Jewish football club in Warsaw. The team was formed in 1925, and its biggest success was reaching the Warsaw B-class in 1932. About 1931, he became a sports journalist, writing for „Der Moment”, one of the most popular Yiddish-language daily newspapers. He was also contributing to „Warszewer Radio”.

In September 1939, Szajnkinder participated in the defense of Warsaw. After being released from the POW camp, he worked at a food aid centre ran by Joint (an American organization helping European Jews) in the Praga district of Warsaw. When the Warsaw Ghetto was established, he worked in the Jewish Social Self-Help Kitchen Central, but his income was not enough to support his family.

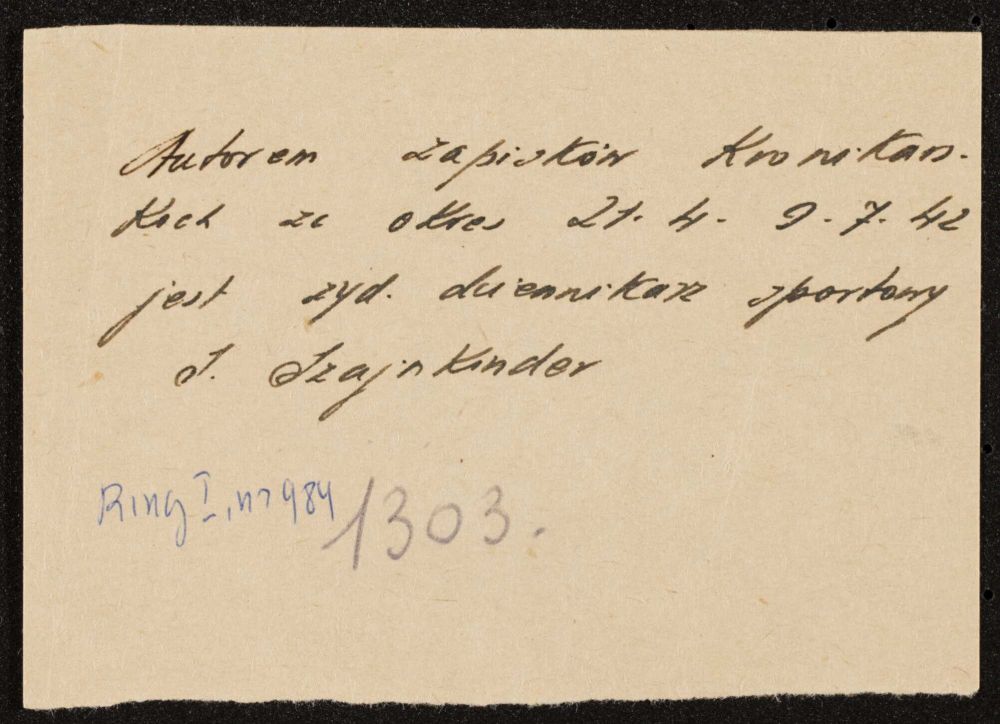

Thanks to his social activism, Szajnkinder met Emanuel Ringelblum. He began his work for Oneg Shabbat probably in early 1942. He was writing only in Yiddish. To the Archive, he contributed his literary works and his ghetto diary, which begins with following words: Tuesday, 21 April 1942. It’s a beautiful spring day. It feels sunny like never before. In the walled ghetto, the air feels stale and suffocating. There’s no trace of greenery, of sprouting plants. The ruins are still surrounded with mud.The yards are filled with piles of dirt and garbage from the winter, and their odour reaches the apartment windows… [1] In his diary, he commented current events, such as shootings in the ghetto in the spring of 1942. He also recalls Chaim Górka, Mojżesz Szklar, Roman Fas and Cwi Pryłucki and describes scenes in which the Jews had to act for the purpose of a propaganda film about the life in the ghetto, filmed by the Germans.

Why are they doing it? For whom? Nobody knows. One can feel that nothing good could come out of it. People keep asking why they won’t film the „exit” at the corner of Karmelicka and Leszno streets, where a policeman smashed with his rifle the head of a 10-year old Jewish boy, who ran with 3 or 5 kilos of potatoes. Why won’t they film the Pawiak prison, from where shots are heard all the time, or Więzienna street, where they arrest passing Jews, take them to Pawiak and make them suffer in a barbaric, (really) horrifying way? [2]

![szajnkinder_2.jpg [283.31 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/1bb359b788404ca39a1f6387469f66a0/jpg/jhi/preview/szajnkinder_2.jpg)

Szajnkinder was writing and editing personal accounts; among them one especially stands out, an account of brothers in arms from the September Campaign called „Daily notes from the September Campaign”, written between 18-21 September 1939. He paid attention to detail, conveying not only facts, but also moods, scents, perfecting the literary expression.

Soon before his death, he managed to write a short story „Four girls” about Ala, Bella, Guta and Zula, who, in order to escape death from famine, earned the money for their bread with their own bodies.

Szajnkinder was murdered during the Great Deportation in the summer of 1942.

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

Footnotes:

[1] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, vol. 23, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, WUW, Warsaw 2015, p. 344.

[2] Ibidem, p. 353.

Bibliography:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, vol. 23, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, WUW, Warsaw 2015.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Wrzesień 1939. Listy kaliskie. Listy płockie, ed. Aleksandra Bańkowska, Tadeusz Epsztein, Justyna Majewska, WUW, Warsaw 2014.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.