- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

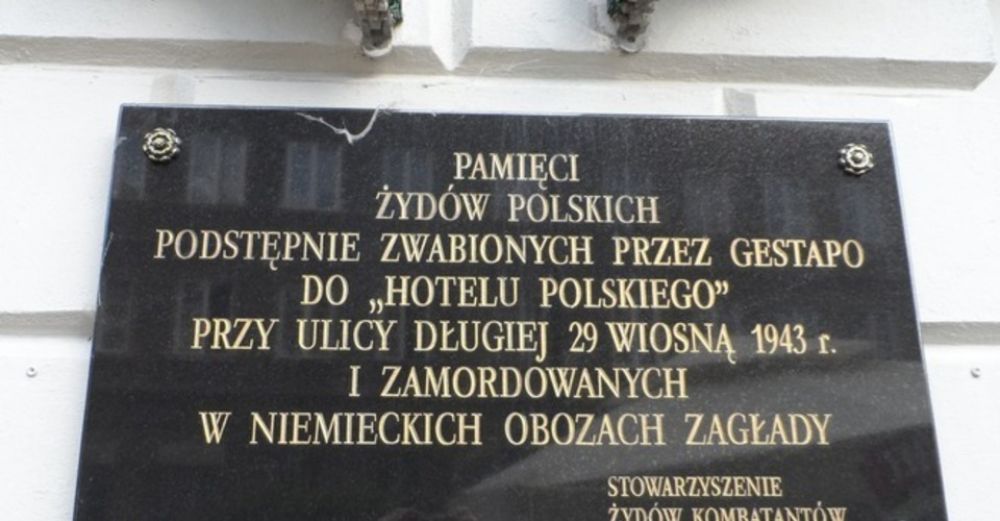

Today is the 70th anniversary of the transfer of the last group of 300 Jews living in Hotel Polski to Pawiak. All of them were shot dead two days later. More than 2,500 Jews hiding on the Aryan side in the spring of 1943 believed in the occupant’s assurance that international passports would guarantee the deportation from the General Government and the rescue from certain death.

The issue of Hotel Polski is still being debated among scholars of the Holocaust, and Długa 29 still remains the most enigmatic address of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Since the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto, the Germans had been raising false hopes on the possibility of the rescue from the occupied capital city. The occupant’s ordinances protected against deportation the Jews who were working in the szops or had entered into a paper marriage with „protected” persons. All these hopes for safety were destroyed at the time of the first deportations to Treblinka. Trapped in the ghetto and becoming more aware of their coming sentence, they looked for every possible help.

After the suppression of the uprising and the liquidation of the ghetto, three groups of Jews remained alive: those working in the szops in the so-called residual ghetto, those hiding in the ruins and burnt buildings and those staying on the Aryan side. The situation of the Jews hiding outside the ghetto was becoming increasingly difficult.

In May 1943, in Warsaw a word was spread that in Długa street documents of South American countries could be bought, which would guarantee the Jews hiding on the Aryan side the possibility to leave the General Government. The destinations of the departure from the occupied Polish territories were to be special camps in France, where the Jews would be exchanged for the German war prisoners interned by the Allies. How did the Gestapo get these documents? In the case of Hotel Polski were involved two Jewish collaborators: Leon „Lolek” Skosowski and Adam Żurawin.

In order to get closer to the answer to this question, we have to go back to the turn of 1941 and 1942 and move to neutral Switzerland. Two Jewish organizations operating there wanted to help the Jews remaining under the Nazi occupation and in cooperation with honorary consuls, they issued documents of South American countries and sent them to Poland. Most of the passports never arrived to their owners, who died during the great liquidation action.

It is not known exactly how, after the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the passports were in Skosowski’s and Żurawin’s hands, who began selling them. In many accounts there is given clear information that they were agents of the Gestapo. At the beginning, the contacting place was in Hotel Royal at 31 Chmielna street, and later Hotel Polski at 29 Długa street. The most common post-war hypothesis is the whole action being prepared by the Germans to reveal as many Jews living in Warsaw as possible. In addition, the internment of the Jews having foreign passports was already present in the General Government.

In his memoirs Henryk Rudnicki writes: “The ones who left were not those who believed the Germans, but those who doubted the possibility of being saved on the Aryan side”. Some of them bought passports, and those who could not afford them, treated Hotel Polski as a temporary place to stay, because their hiding place had been „burnt”. In Hotel Polski you could buy passports and promissory notes of such countries as Paraguay, Honduras, El Salvador, Peru and Chile that could be bought on prices ranging from 30 to 300 zloty, or for gold or other valuables. In Długa they interned among others: Zionist activist Menachem Kirszenbaum, writer Yehoshua Perle and poet Yitzhak Katzenelson.

The third person involved in the case of Hotel Polski was a former JOINT’s director, Daniel Guzik, thanks to whom the so-called Palestinian list was created. According to the accounts, he did not take any money and he believed in the success of the action. When asked by Cukierman, why he was working with Jewish collaborators, he replied: „If I know that I can save even just one Jew, I will be ready to kiss Żurawin’s and Skosowski’s asses”.

The destinations of the transport of about 2,000 Jews who bought the passports were Vittel and Bergen-Belsen, from where they were supposed to emigrate overseas. In September 1943 the Reich Main Security Office realized that the holders of the passports were not their owners, and South American countries did not want to recognize them as their citizens. All of them were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. From more than 2,500 Jews who had come to 29 Długa street, only 260 people survived.