- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

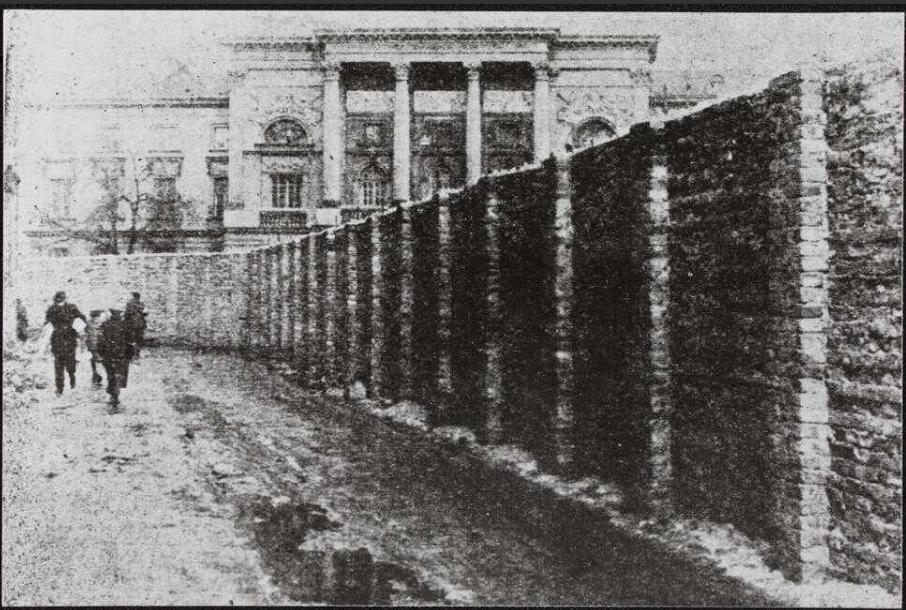

The wall divided Warsaw in two. Even though three districts were established, the wall became the main division line [1]; it cut natural communication routes, destroyed the topography of the city. Streets have turned into a complex ‘labyrinth’. Thousands of people were forced to leave their homes. The change had affected all areas of human life – organization, customs, psychology, language [2] and many others. Building the wall had also a complex symbolic dimension. Stanisław Różycki wrote that going through the wall meant crossing the limits of imaginable reality. [3]

16 November was a decisive day for the Jews of Warsaw. On that day, 400,000 people were imprisoned within the walls. The Jews were cut off the streets of Warsaw, from information [4], bloved ones who have stayed on the ‘aryan side’, food, nature, trees, the view of sky reaching the horizon. The immediate result of closing the ghetto was an increase of food prices and hunger, affecting the poorest in the first place. The Germans had increased propaganda in order to justify closing the walls, they also imposed the term Jewish living district instead of Jewish ghetto. [5] Yet the street had no doubt about the intentions of the occupant. It was said: ‘we have been buried alive’ (Ringelblum quotes the phrase), and the walls themselves were seen as a civilizational regression, a return to medieval times. [6] The ghetto was even compared to a concentration camp, with the only difference being that in the ghetto people have to make a living on their own. [7]

The walls which were built on Rymarska street were lifted and look like real prison walls. People believe that they want to bury us alive. [8]

Literature contains such phrases as ‘trapped by walls’, ‘pressed’. [9] Jehoszua Perle adds: in the area surrounded with ‘grim’ walls, built by the Jewish Council with their own money, there is no space to breathe [10], and people suffocate in narrow, dirty, dark streets. [11] Icchak Berensztein in one of his poems compares the Jews to rabbits squeezed in hutches, separated from the world with a two-metre high wall. [12]

Ringelblum wrote: The ghetto affects us more than in medieval times, because we were so high, and we have fallen so low. An appeal for searching for positive sides of the ghetto: a tendency to flatten silk and clothing tax, mutual help, animated social life. [13]

Freedom is symbolized by the horizon line, whose view is denied to the people of the ghetto forever.

There is one thing missing in our ghetto sky: horizon. The ghetto is so small and surrounded by walls and ruins. There is no space to freely look at a wider piece of sky with the horizon. We see it only like prisoners in their cell. It’s really sad and depressing. [14]

The ceiling of the sky seems to close the space surrounded by walls, to complete the misfortune of the Jews. There is rain, snow or heat from the sky; the air in the walls of the ghetto is stale and suffocating. [15] The sun doesn’t help either – it brings to the front the whole poverty and dirt in the ghetto, where there is no trace of greenery, of fresh plants [16] and makes things even worse.

Building the ghetto walls

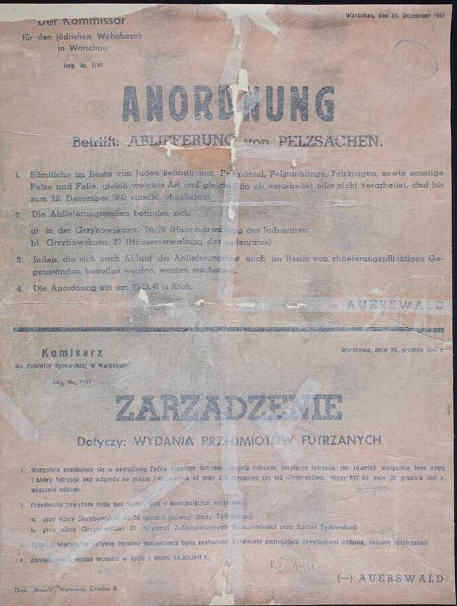

Before 16 November 1940, different kinds of walls were built around the Jewish community, gradually worsening the living conditions, limiting rights, pushing onto the margin of social life and separating from the Polish society. Building the physical wall and closing the ghetto was another stage of a process which had begun before. In October 1939, Germans introduced a labour order for Jews aged 14–60 (26.10.1939), closed Jewish schools (15.11.1939), ordered to mark Jewish shops (23.11.1939) and on 1 December 1939, introduced obligatory bands with the Star of David. The next months saw further limitations: a ban on moving house without permission (01.1940), mass prayer (01.1940) and others.

Gossip about closing the ghetto began to circulate in Warsaw quite early, Ringelblum mentions it already in February 1940. The gossip was the main source of information – the street speculated about the purpose and location of walls. It was said that there will be no ghetto and that the purpose is holding the Jewish community ransom. [17] They said about a fortune-teller who claimed that the ghetto wall will disappear this month, namely June. [18] There were also jokes. [19]

The Germans were denying the gossip about the ghetto in official announcements, but at the same time, they were preparing to establish a Jewish district. Already in November 1939, at the endings of some streets appeared first barbed wire fences and warnings ‘epidemic, no soldiers allowed’. On 23 January 1940, a Resettlement Department (Umsiedlung) was established at the Warsaw District Administrator’s Office, directed by Waldemar Schön and aimed at organizing ghetto in Warsaw.

Ringelblum wrote in March 1940: Today, on March 2, they began to build walls around the epidemic area. It made a big impression. People believe it is a beginning of an actual ghetto. [20]

On 27 March 1940, the Judenrat received an official order to build – from their own funds – a wall around the ‘epidemic area’ (as mentioned by Ringelblum; Czerniaków writes in his Diary about organizational problems related to the construction).

At that time, between 22 and 29 March, anti-Jewish violence inspired by Germans was taking place in Warsaw – shops and apartments were plundered, people on the streets were attacked. The German propaganda used these acts to justify the construction of the ghetto in order to protect the Jewish community from anti-Semitism and Polish community from an epidemic. Such thinking about the ghetto walls – the alleged anti-pogrom protection – was functioning in the ghetto quite long; Ringelblum wrote in June 1941: Thankfulness for the walls around the ghetto, fear of pogroms – similarity to Verona in 1599. Pogrom moods in the first days of war against Russia (…) robberies i Praga – joy from having the walls and fear of demolishing them. [21]

At the same time, Waldemar Schön, the founder of the ghetto, justified the decision about building the walls by necessity of anti-epidemic protection, eliminating Jewish influence from politics and morality and necessity to remove illegal trade. He boasted that the process took six weeks withour bloodshed.

On 1 April 1940, the Judenrat, following the occupant’s order, began to build the walls at their own cost. Ringelblum wrote: In Warsaw, they’re building a wall on theNalewki – Kramy Nalewkowskie – Przejazd – Nowolipie line. They’re believing it is a beginning of a ghetto, which will suddenly become a fact. [22] The construction was finished in June 1940, and the ‘epidemic area’ was marked by warning signs.

On 7 June 1940, according to an order from Ludwig Leist, Reich commissioner in Warsaw, the Jews were supposed to move away from the future German district. For a limited time, they were allowed in the Polish district. Jews who arrived in Warsaw were ordered to move to the ghetto. Expulsion and resettlement began. On 20 August, the Resettlement Department restored the works on organizing the ghetto. On 31 August, the Jewish Newspaper published a list of border streets and the city map.

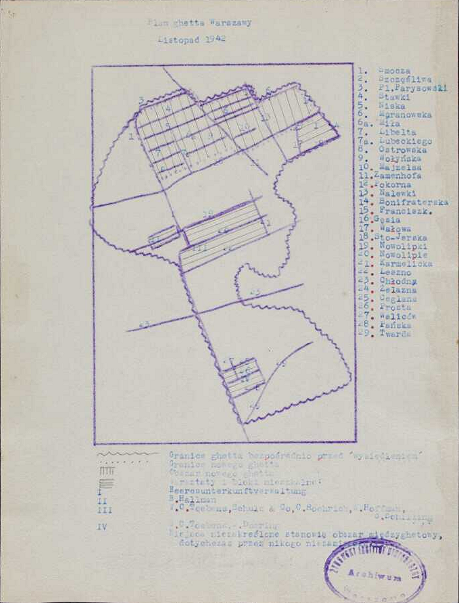

Establishing the ghetto

On 2 October 1940 Ludwig Fischer, governor of the Warsaw district, signed an official order of establishing the ghetto with the list of border streets. It was announced through street loudspeakers on 12 October – on Yom Kippur, the Judgement Day. The border streets were supposed to be completely aryan, and the border was not on the street line, but between houses. The area was different from previous plans. In the following days, the borders of the ghetto were going through further changes, which caused people to move two or three times. [23]

Today, the Sabbath of 12 October, was a horrible day. Through loudspeakers, they announced the division of the city into three parts: German one with the centre and Nowy Świat, Polish and Jewish ones. Until the end of October, everybody except from Germans were supposed to move house, without furniture. Despair in our house. The owner has been living here for 37 years and now she has to move away, withour furniture. Thousands of Christian shops and businesses would be ruined this way. [24]

The Jewish New Year was peaceful. Only on the Judgement Day, about 2, they were announcing through the speakers that the German, Polish and Jewish districts will be established. They mentioned the limits of the Jewish and German districts (…) The gossip began to spread and cause panic. It was said that the Jews who will be moving to the Jewish district won’t be allowed to take anything. Despite that, the Jews remained calm through the festival. I managed to observe that in the houses where there were prayers, they remained undisturbed by announcement of the ghetto. [25]

The official text of the announcement with the list of border streets of the ghetto was published on 15 October 1940 i n the ‘New Warsaw Courier’. The Warsaw exodus began: 138,000 Jews and 113,000 Poles had to move. Institutions from the aryan side had to be moved as well – in December 1940, the Jewish hospital at Czyste was evacuated, as well as two orphanages – Korczak’s Orphan House from 92 Krochmalna to 33 Chłodna street and the orphanage from 26 Jagiellońska to 28 Śliska street. People who had to leave their apartments were in a much worse situation. The operation was difficult on many levels.

The resettlement day approaches, and 10,000 people still have no place to live (…) after several weeks of searching, I have finally found an apartment. Much worse, but it is there. I am facing new challenges. No money to move. Asking the office in which I work seems to make no sense. It’s difficult to sell things, no buyers. Many speculators around. Prices for clothing and household goods fall proportionally to the rise of food prices. The situation seems to have no solution. [26]

The view of the Jews carrying their things made an awful impression. They carried furnture ven though it was not allowed. There were cases when carriages with furniture were stopped and taken away. The whole city is plastered with white announcements about exchanging apartments by Jews and Christians, the entire wall next to the Accommodation Office is all white. [27]

On 6 October, Jews were banned to leave houses between 7 PM and 8 AM. at the same time, Ringelblum wrote on 8 November that the fear of closed ghetto increases, especially that it was said today that the Polish police was told to leave the ghetto. Everyone is gathering things. [28]

Closing the ghetto

On 27 October, German authorities agreed to extend the procedure until 15 November – the decision was announced through speakers on the last day of October, and the borders of the ghetto were changed again.

Eventually, the ghetto was closed on 16 November 1940. the area covered 307 ha of buildings, with 400,000 people living in 1483 houses. Even though the order was clear, people still didn’t believe in the closing of the ghetto.

Ringelblum: The Sabbath on which they established the ghetto (16 November) was awful. The street didn;t know that the ghetto will be closed, so the decision was sudden. The German, Polish and Jewish guards were placed on all crossings to control who is allowed to pass. [29]

The occupant’s plans were kept secret. Nobody knew if the ghetto will be opened to facilitate communication between Jews and Christians, or closed like in Łódź, where people were condemned to hunger and disease. Or maybe – some believed that it was a plan to force some contribution from the Jewish community? Optimists believed that the order will be cancelled, like last year. But on 15 November, at night, closing of the ghetto became a fact and nobody dared questioning it. The German gendarmerie was controlling passages between ‘Jewish’ and ‘Christian’ streets which were built over due to piublic transport. When the people of Warsaw were going to work at 5 AM, they were surprised: the Jewish district was cut off from the rest of the world. [30]

he district was supposed to be closed on 15 November, but nobody believed in the actual closing. Many were susprised when the walls of the Jewish district became surrounded by German guards on 15 November. [31]

Poles were allowed to go freely into the ghetto until 26 November. There were 22 gates to the ghetto (wachy). The Germans would systematically decrease their number – in February 1942 there will be 8, in June 1942, before the Great Deportation, they would remove further two.

There were several types of guards of the walls and exits, and their number kept increasing. The walls were guarded by gendarmerie with the blue police, a double line of gendarmerie were placed at the gate of the ghetto, along with Jewish Order Service. Sonderdienst, called ‘junaks’ in the ghetto, were patrolling and looking for smugglers’ carriages. The Gestapo was arriving often at the ghetto gates, and the SS were guarding the exits along with the Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Latvians during deportations. [32]

At certain exits, especially at Żelazna – Chłodna, awful scenes were taking place. German guards required bowing from passing Jews, they were stopping the Jews and telling them to exercise with bricks in hands, climb walls, lie down in the mud etc. One day at the corner of Żelazna and Chłodna, German guards have stopped a street orchestra, told them to play, and one elderly lady and an old Jew with white beard were ordered to dance and threatened to be beaten. They were photographing these scenes. [33]

Hunger and smuggling

The first and the most serious consequence of closing the ghetto was an increase in prices of food and hunger which affected the poor, refugees, the sick, children, the elderly. Ringelblum wrote that German authorities did everything to close the ghetto hermetically and not let any food in. they walled the ghetto from all sides, without a milimetre of free space. [34]

It can be clearly seen in children’s accounts: Until they have closed us in the Jewish district, we were able to make a living with my sister. We were living a humble life. Later, prices rose and we began to suffer hunger; When they established the Jewish district, everything turned worse for us, We didn’t know hunger until they closed the Jewish district, The Germans have established the Jewish district. Poverty and hunger began to spread. People died of hunger, young and old. [35]

People quickly began to organize smuggling. Ringelblum writes that smuggling was organized through 1) walls, 2) exit gates, 3) underground tunnels, 4) canals and 5) border houses. [36] Various methods of getting though walls or killing the smugglers were described in many documents from the Archive, such as the Diary by Daniel Fligelman, or by Abraham Lewin, who was living by the wall dividing the ghetto from Przejazd and regularly described the fate of smugglers and their work.

Social roles shifted – now children, who were able to sneak through a hole in the wall, became the main supporters of their families. The walls were for them a barrier to cross in order to find food, but on the way back – as described in the Ringelblum Archive – were a symbol of relative safety. Children didn’t want to leave the ghetto and returned to their families. They were also struggling for warmth – despite freezing cold due to lack of firewood, people in the crowd offered each other some warmth.

The Germans kept adding layers to the walls, installed barbed wire or broken glass in order to reduce smuggling. [37] They kept locking the exits. Despite that, the need to find food was stronger than these means.

hey close more exits. It reduces the possibilities of smuggling and puts the ghetto in a threat of dying from hunger. With such small amount of provided food, we can easily starve to death. [38] In the context of smuggling, the wall is a symbol of division, but also something that connects – as Ringelblum writes: Poles and Jews shook hands over walls and barber wires in order to resist the inhuman plans of the occupant to starve 400,000 people to death. Extraordinary invention, energy on both sides, along with demoralization of the ‘victorious’ German army and its supporters, who fell prey to money, made the plan of Auerswald, the commissioner of the Jewish district, burst like a bubble. [39]

The Great Deportation

On 16 November 1940, nobody from the 400,000 members of the Jewish community in Warsaw would assume that they would leave the ghetto walls – in a train to Treblinka. On 23 June 1942, the borders of the ghetto were changed for the last time before the deportation. The Germans, who were keeping their plans to destroy the Jewish population concealed, used the walls as a symbol of stability in order to calm people down. Ringelblum writes:

Leaders of the ŻSS Gustaw Wielikowski and Józef Jaszuński returned from Kraków and claimed that the head of the ‘Bevölkerungswesen und Fürsorge’ department, Türk, told them that deportations from Warsaw won’t take place. The ghetto is a separate state surrounded by walls and will remain this way until the end of the war. The resettlement will take place after the war. [40]

On 22 July 1942, the Great Deportation began. The moods were horrible. From early morning, mothers and fathers left houses to earn some money to feed their children. They took them away, without children. The children found on the streets were taken away without parents. Shouts and cries reached beyond the ghetto walls. [41]

For the insurgents, breaking the walls, standing on them, was a symbol of victory and freedom. Dawid Graber called: Let’s die like heroes. Let’s burn the ghetto at night from all sides. Let the Jews leave their houses, climb the walls with knives and axes and attack the German guards. Let them shoot us all. [42]

----------------------

The walls were destroyed along with the Northern district. Fragments preserved from the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising can be found in the courtyards at 55 Sienna, 62 Złota and 11 Waliców street.

In 2008, at the initiative of the Jewish Historical Institute and the Warsaw Conservator, a project of the memorial to the borders of the Warsaw Ghetto was designed. 22 plaques and concrete slabs recreate the shape of the Warsaw Ghetto borders in Wola and in the centre. The memorials commemorate the furthest reaching points of the ghetto. They were installed in places where between 1940–1943 there were gates, wooden bridges over aryan streets and buildings important for the people living in the Warsaw Ghetto.

(translated by Olga Drenda)

Footnotes:

[1] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018, p. 368.

[2] Szaul Stupnicki discusses the epidemics of polonisation: The second reason: the Jews are crowded in the ghetto, looking for contact with the outside world, but there is no contact. The walls are closed, and a Jew is hanging on to foreign language for help and this way he believes he remains in contact with the world, with the other side [in:] Odpowiedzi żydowskich intelektualistów i naukowców na ankietę dotyczącą oceny sytuacji ludności żydowskiej w getcie warszawskim [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, vol. 26, ed. Agnieszka Żółkiewska, Marek Tuszewicki, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p.39.

[3] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie, cz. 1, vol. 33, ed. Tadeusz Epsztein, Katarzyna Person, Wyd. UW, Warsaw 2016, p. 45.

[4] We don’t receive any messages from that side of the wall [in:] Abraham Lewin, Dziennik [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, vol. 23, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, Wyd. UW, Warsaw 2015, p. 128.

The wall prevented communication between the Polish and the Jewish side, but it was also a location for informing people of Warsaw about what was happening in the ghetto, and about regulations regarding helping the Jews: On the aryan side, posters were placed. Within 10 days, the Jews can move into the ghetto without any punishment. Hiding Jews is punishable by death. For the first time, a warning for Germans appeared on the posters as well [in:] Jechiel Górny, Dziennik [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, vol. 23, op. cit., p. 333.

[5] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p. 160.

[6] Stanisław Różycki, Ulica [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, vol. 5, ed. Katarzyna Person, JHI, Warsaw 2011, p.51.

[7] Ringelblum: In practice, the ghetto was something of an autonomous area with local authorities, with Order Service, post, arrest, even its own metrology office. The Jews were calling it a concentration camp surrounded with walls and barbed wire, but one in which people have to make a living on their own. [in:] Emanuel Ringelblum, Stosunki polsko-żydowskie, Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, vol. 29a, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018, p.37.

[8] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vo. 29, op. cit., p. 154.

[9] N.N., Warszawskie getto [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, op.cit., p. 96.

[10] They are surrounding us with a wall again. [1]The wall will run through the middle of Gęsia, Franciszkańska, up to Bonifraterska. There will be no space to breathe [in:] Jehoszua Perle, Zagłada Warszawy [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, vol. 26, op.cit., p.555.

[11] Ibidem, p.523.

[12] Icchak Berensztein, Poematy prozą [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p.492.

[13] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p. 160.

[14] Abraham Lewin, Dziennik [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p.88.

[15] Sz. Szajnkinder, Z mojego dziennika [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p.344.

[16] Ibidem, p.344.

[17] Natan Koniński, Zamknięcie ghetta [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, op. cit., p.17.

[18] Abraham Lewin, Dziennik [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, op. cit, p. 72.

[19] Ringelblum: they call the walls an extension of the Siegfried line [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p. 105.

[20] Ibidem, p.82.

[21] Ibidem, p. 273–274.

[22] Ibidem, p. 110.

[23] Natan Koniński, Zamknięcie ghetta [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, op. cit., p.17.

[24] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p.144.

[25] Natan Koniński, Zamknięcie ghetta, op. cit., p.16.

[26] H.S. L., Relacje o traktowaniu Żydów przez ludność polską w Warszawie [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, op. cit., p. 424–425.

[27] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p.146.

[28] Ibidem, p.159.

[29] Ibidem, p.166.

[30] Jehuda Feldwurm, Zbiór opowiadań [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p.359.

[31] Natan Koniński, Zamknięcie ghetta, op. cit., p.17.

[32] Emanuel Ringelblum, Stosunki polsko-żydowskie [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, op. cit., p. 44–45.

[33] Natan Koniński, Zamknięcie ghetta, op. cit., p.18.

[34] Emanuel Ringelblum, Stosunki polsko-żydowskie, op. cit., p. 44–45.

[35] Dzieci o losach swoich rodzin. Odpowiedzi na ankietę rozpisaną wśród uczniów kompletów tajnego nauczania w półinternacie przy ul. Nowolipki 25 (statements in order: Chana Rozenblum, p. 10; Sz. J. Saluńczyk, p. 19; Andzia Baranek, p. 20; Zalcwas Szlama, p.22 [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzieci – tajne nauczanie w getcie warszawskim, vol. 2, ed. Ruta Sakowska, JHI, Warsaw 2000.

[36] Emanuel Ringelblum, Stosunki polsko-żydowskie, op. cit., p. 44–45.

[37] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p.234, 237.

[38] Ibidem, p. 247.

[39] Emanuel Ringelblum, Stosunki polsko-żydowskie, op. cit., p.47.

[40] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, op. cit., p.370.

[41] Nachum Grzywacz, Dziennik [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p. 386.

[42] Dawid Graber, Relacja [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, op. cit., p.381.

Bibliography:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzieci – tajne nauczanie w getcie warszawskim, vol. 2, ed. Ruta Sakowska, JHI, Warsaw 2000.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, vol. 5, ed. Katarzyna Person, JHI, Warsaw 2011.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, vol. 23, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, Wyd. UW, Warsaw 2015.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, vol. 26, ed. Agnieszka Żółkiewska, Marek Tuszewicki, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, vol. 29a, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie, cz. 1, vol. 33, ed. Tadeusz Epsztein, Katarzyna Person, Wyd. UW, Warsaw 2016.

Barbara Engelking, Jacek Leociak, Getto warszawskie. Przewodnik po nieistniejącym mieście, Wyd. IFiS PAN, Warsaw 2001.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.