- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Around 800 000 Jews lived in Romania, which at the time of the Second World War was a satellite country of the Third Reich. The countries authorise attempted to get remove them through many means. Between 1941 and 1942, dozens of antisemitic bills and decrees were published. The culmination of the anti-jewish policies was the pogrom in Iași, which took place between the 27th and 29th of June 1941, when at least 13 266 Jews were murdered on the urging of dictatorial Prime Minister Ion Antonescu.

While leaving for Palestine was impossible for Jews from the Third Reich and the lands occupied by it, it was possible — though not without great difficulty — in countries dependent on Germany, such as Romania. The initiators of one such attempt in 1941, were the members of the New Zionist Organisation and Betar, who rented out the decades old Greek ship “Struma”. It was meant to transport Jews who were in danger of being murdered in Romania, to Turkey, from which they would continue on to Palestine.

In fact, “Struma” was a well-worn barge, adapted for the purpose of transporting cattle down the Danube, which could fit 100–150 people at most. However, around 800 people, including over 100 children, ended up on “Struma”. Encouraged by the advertisements of a “tourist” expedition to Palestine, as the trip was promoted by the organisers, they were shocked when they finally saw the ship. Even more so, because the price of a ‘ticket’ was equivalent to a thousand dollars. Despite the high price and the abominable conditions, it was still the only chance of escaping Europe, where the lives of the Jewish population were endangered. After four days spent on formalities and being robbed of their possessions by the customs officers, the masses of people who showed up in the Constanța port on the 8th of December 1941, finally found themselves aboard the ship and on their way to Istanbul on the 12th of December.

Sailing under a Panama flag, “Struma” needed 4 days (as opposed to the regular 14 hours) to reach the city over the Bosphorus. The ramshackle sate of the ship and its failing engine meant that it had to be hauled to shore by Turkish vessels. That was when the tragedy of the Jewish refugees began — the Turkish authorities refused to let them disembark, and the ship was in no condition to continue the journey.

Anti-refugee Politics

Turkey’s reluctance to assist the refugees was due to the political situation of the country during the war. The authorities tried to maintain balance between Great Britain, which which they shared a defence treaty since October 1939, and the Third Reich with which Turkey had singed a treaty of friendship and non-aggression in June 1941. The British, who were disinclined to accept refugees in Palestine, opposed the admittance of “Struma’s” passengers on the pretext that Romania, from which the ship had sailed, was at war with Great Britain since the 7th of December 1941. Most of the passengers had Romanian passports, others had Hungarian or Bulgarian ones, thus they were all citizens of countries hostile to Great Britain. Only 4 people, who possessed valid Palestinian visas, received permission to come ashore and continue on to Palestine. The British claimed the remaining passengers might be Nazi agents, since they arrived from hostile territories and might be “working in support of the enemy”. The position of the British was not influenced by the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the organisation representing the Jewish settlers in Palestine, arguing that the limits established in the British “White Paper of 1939” regarding the number of immigrants, had not yet been reached. The authorities did not wish to set a precedent, fearing a massive influx of refugees in the future. However, in the case of non-Jewish refugees, for instance Anders’ Army soldiers and the civilians accompanying them, who after some time ended up in Palestine, were treated differently, as it was known that, unlike the Jews, they would not remain there permanently and will not be a problem. In this situation, the Turkish Prime Minister Refik Saydam said: “It cannot be expected that Turkey will serve as shelter or a new homeland for people who are not wanted elsewhere”.

The Jewish Agency for Palestine appealed to the Turkish and British authorities in January and February 1942, however the appeals went unanswered. Meanwhile, almost 800 people were stranded in tragic conditions on “Struma”, docked in Istanbul. One of the four people who, possessing Palestinian visas, were allowed to leave the ship, called it later “a floating coffin”. The cabins were freezing and fetid, there wasn’t enough food or places to sleep, the ship had only one toilet. Simon Brod, a Jewish merchant form Istanbul, tried to assist the refugees; he bribed the Turks to supple the ship with water and food, but this did not suffice to cover the refugees’ needs.

In the meantime, the situation became even more complicated. In January 1942, Panama declared war against Germany and its allies, in response to which the Bulgarian crew of “Struma” refused to serve on a vessel under enemy colours. The Wannsee Conference, during which the Germans decided on the Final Solution to the Jewish question, also took place in January. On the 15th of February, there was one last chance to save children aged 11 to 16, for whose upkeep the Jewish Agency for Palestine vowed to provide, however, the Turkish and British authorities did not allow it.

The impasse held until the 23rd of February 1942. 75 days after leaving Constanța, “Struma” was hauled away from the Istanbul port by the Turks, and left to drift on the sea.

Death on the Black Sea

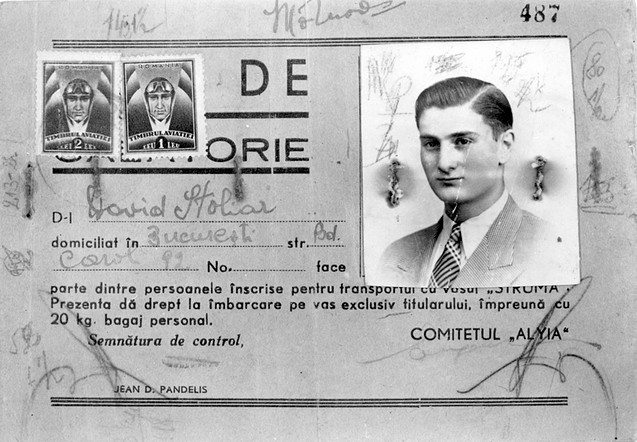

A day later, on the 24th of February 1942, a tragedy took place. “Struma” was torpedoed by the Soviet submarine “Shch-213” which was patrolling the area. Around 500 refugees died as a result of the explosion, the rest perished due to wounds, exhaustion and hypothermia. The Turks delayed sending help, which finally arrived 24 hours after the attack. Only one passenger was saved — David Stoliar, who was 19 years old at the time. He survived thanks to the thick coat he had received from his father before the journey. Years later, Stoliar wrote: “Immediately after the explosion, I jumped into the sea. I hung on for about 24 hours. I remember the Turkish lifeboat arriving.”

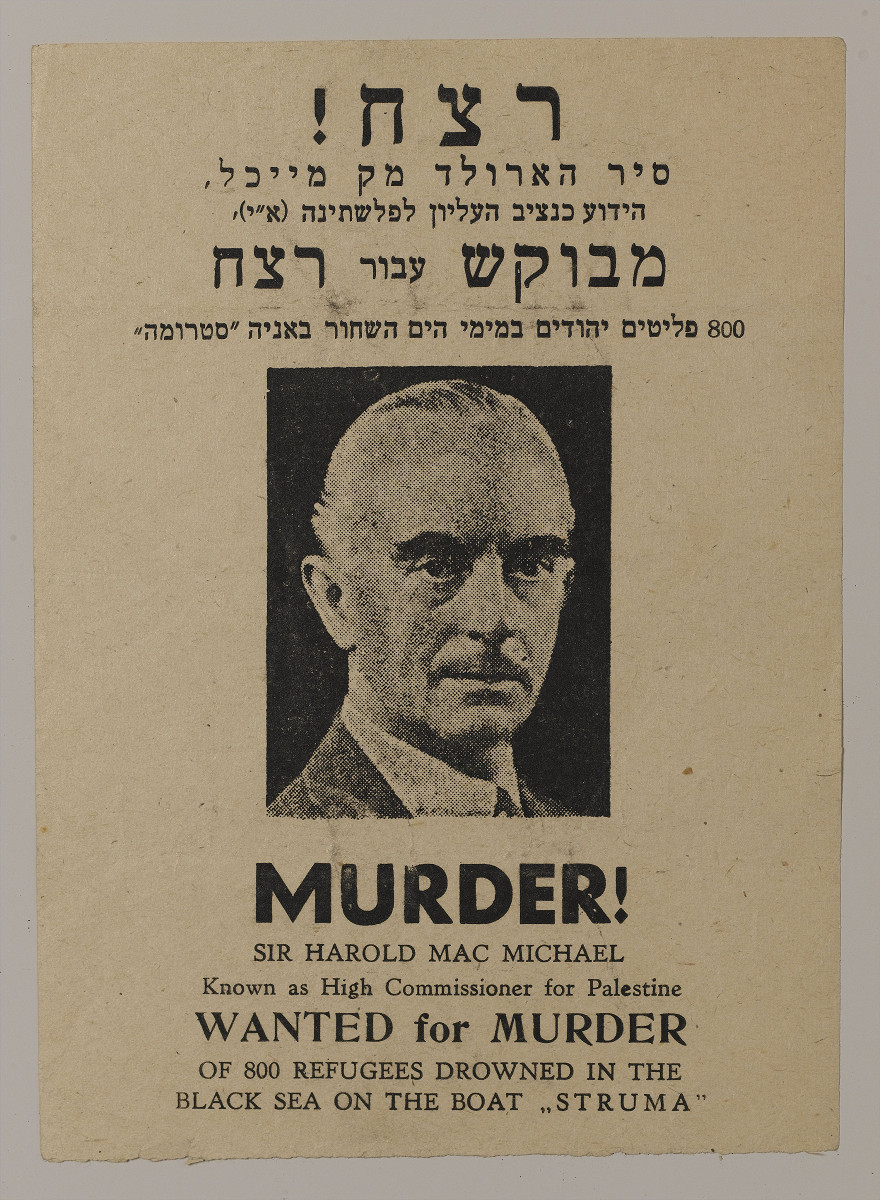

Stoliar was placed in hospital, from where — having been accused entering Turkey illegally — he was taken to jail for six weeks. Finally, the British authorities agreed — for humanitarian reasons, as they claimed — to let him enter Palestine. This was allowed against the protests of Sir Harold MacMichael, the High Commissioner of the British Mandate of Palestine, who warned that admitting Stoliar into Palestine would create a precedent and “utterly undermine our policy regarding illegal immigrants”. Stoliar himself reminisced: “after freeing me, the Turkish gendarmes escorted me all the way to the boarder with Syria”. Simon Brod helped transport him, organising a train to Aleppo and a car to Tel Aviv.

After the tragedy

The “Struma” disaster incited protests and demonstrations in Palestine and the US. In Palestine, many posters appeared, with the image of Commissioner MacMichael, and the caption “wanted for murder”. However, these events have been often overlooked, both at the time and presently, because the Jews did not die directly at the hands of the Nazis. Nevertheless, prominent people have expressed solidarity with the victims; Albert Einstein, for instance, said that the tragedy “strikes at the very heart of our civilisation”, while the American First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt called it “a cruelty there are no words to describe”. An intense debate took place in the House of Commons, during which MacMichael was criticised for his decisions which showed a lack of humanity and an excessively rigid adherence to regulation.

Nevertheless, the tragedy helped Zionists understand that they cannot rely on British assistance in establishing their country. In May 1942, during a conference organised in New York by David Ben-Gurion, one of the leaders of the Zionist movement, the topics of creating and independent Israel and overturning the limitations on Jewish immigration to Palestine were brought up and widely discussed. At the time, the British were willing only to rescind the ban on Jews from areas occupied by the Third Reich immigrating to Palestine. However, this only happened in July 1943 when, in light of the Holocaust, the possibility of Eastern-European Jews emigrating in large numbers was no longer a real danger in the eyes of the British.

After the war, David Stoliar settled in Palestine, fought for Israel’s independence, and in 1970 moved to the US, where he died in 2014.

Remembering “Struma”

On the 3rd of September 2000, a ceremony in remembrance of the tragedy was held in Turkey, attended by 60 members of the victims’ families, representatives of the Jewish community in Turkey, the Israeli ambassador and the Prime Minister’s emissary, delegates from the US and Great Britain. Due to personal reasons, the only survivor of the “Struma” disaster — David Stolier — was not present.

On the 26th of January 2005, the Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, told the Knesset: “The leadership of the British Mandate displayed obtuseness and insensitivity by locking the gates to Israel to Jewish refugees who sought a haven in the Land of Israel. Thus were rejected the requests of the 769 [sic] passengers of the ship “Struma” who escaped from Europe – and all but one [of the passengers] found their death at sea. Throughout the war, nothing was done to stop the Holocaust”.

Today, “Struma” serves as a street name in certain Israeli cities. There are also monuments created in remembrance of the tragedy, as well as a synagogue in Beersheba which bears the ship’s name.

The “Struma” disaster is one of the most tragic events in the history of Jewish wartime migration to Palestine. Although it has been forgotten, to a large extent, it is worth remembering, particularly today when the authorities of many countries, including Poland, see refugees trying to survive, primarily as a threat and not people in need of help.

Bibliography

Artur Płatek, Żydzi w drodze do Palestyny 1934-1944. Szkice z dziejów aliji bet nielegalnej imigracji żydowskiej, Kraków 2009, pages 236-256.

Dalia Ofer, Escape the Holocaust. Illegal Immigration to the Land of Israel, 1939-1944, New York – Oxford 1990, pages 147-182.

http://jewish.pl/pl/2016/03/09/tragedia-statku-struma-1942/ (accessible as of 1.02.2017)

http://biblioteka.netgenes.pl/lekcja-plywajacej-trumny.html (accessible as of 1.02.2017)

http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/the-lone-survivor-of-a-jewish-refugee-ship-1.414588 (accessible as of 1.02.2017)

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/interview-with-lone-survivor-of-torpedoed-jewish-refugee-ship-struma-a-901490-2.html (accessible as of 1.02.2017)

http://turkishjews.com/struma/ (accessible as of 1.02.2017)