- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

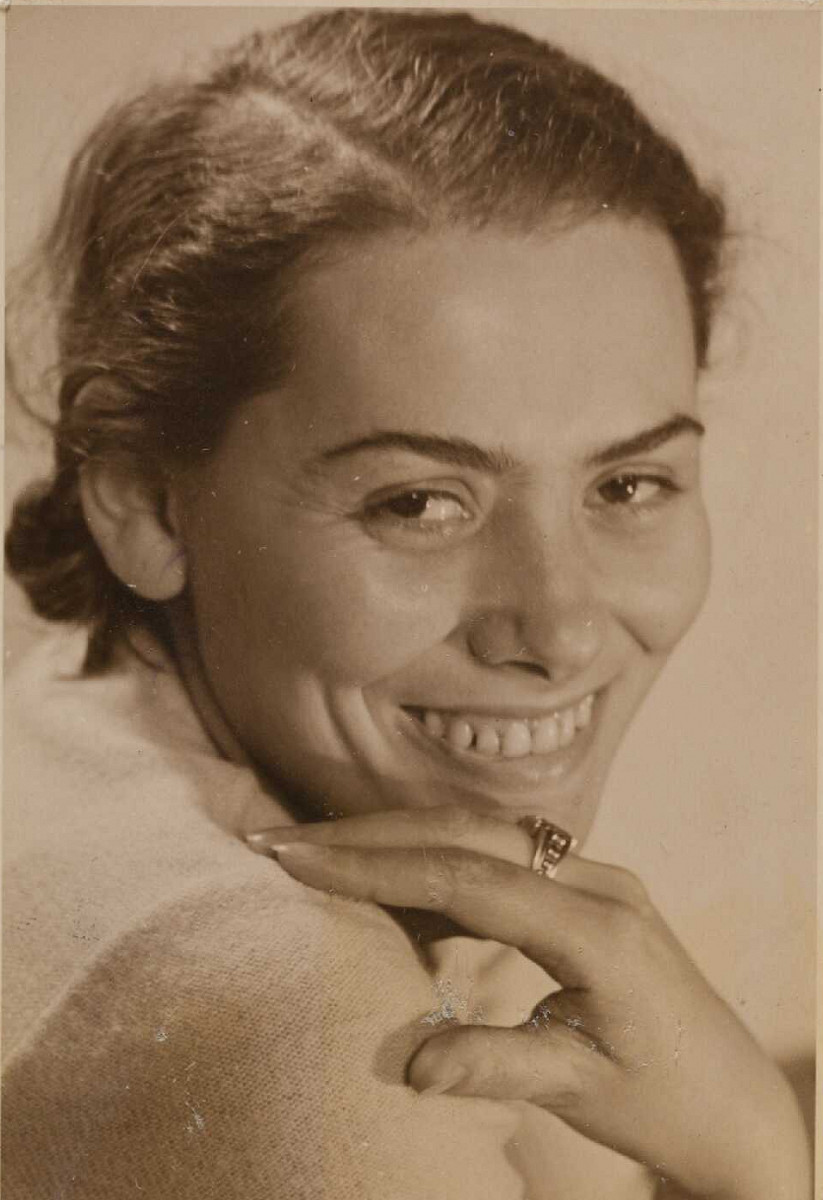

Gela Seksztajn was born in 1907 in Warsaw, in a working-class family. Her mother had an intelligentsia background (her family name was Landau), and father worked as a cobbler. This misalliance may have been caused by Gela’s mother’s physical disability, she had a paralysed hand. She died in 1918, when Gela was 11. From that moment on, the girl was living on her own, a teacher named Oruszkes-Zusman took custody of her. Gela recalled this period in her life briefly: I had acceptable conditions, I was living with strangers, it was tiresome. [1] She attended a 6-class primary school at 68 Nowolipki street and completed a course in tailoring, as she had to make a living early.

She had displayed a talent for arts since early age. I was interested only in painting, she recalled. [2] Her talent was discovered by Izrael Singer, an older brother of Isaac Bashevis Singer. He contacted her with actor and director Jonas Turkow, who in turn got her in touch with sculptor Henryk Kuna. With his support, Gela received two-months grant from the Ministry of Religion and Public Enlightenment for education at the Academy of Arts in Kraków. In Kraków, she spent about 13 years. She made her first artworks and worked at a photography atelier as a retoucher of film stills.

In 1937, she moved to Warsaw. In November, Izrael Lichtensztajn, her future husband, wrote to his brother Szlomo: There is a girl I’d like to be with. She is working too, as a painter. She is a very intelligent and nice girl. [3] They got married in 1938, moved in to a flat at 5/10 Nowolipie street, and later at 29 Okopowa street.

On 4 November 1940, their only child, daughter Margolit, was born. She is my joy and my pride. A great, talented, pretty child. She is also my pain and my drama. If I wanted to live, I would only for my dearest daughter, wrote Gela soon before she died. [4]

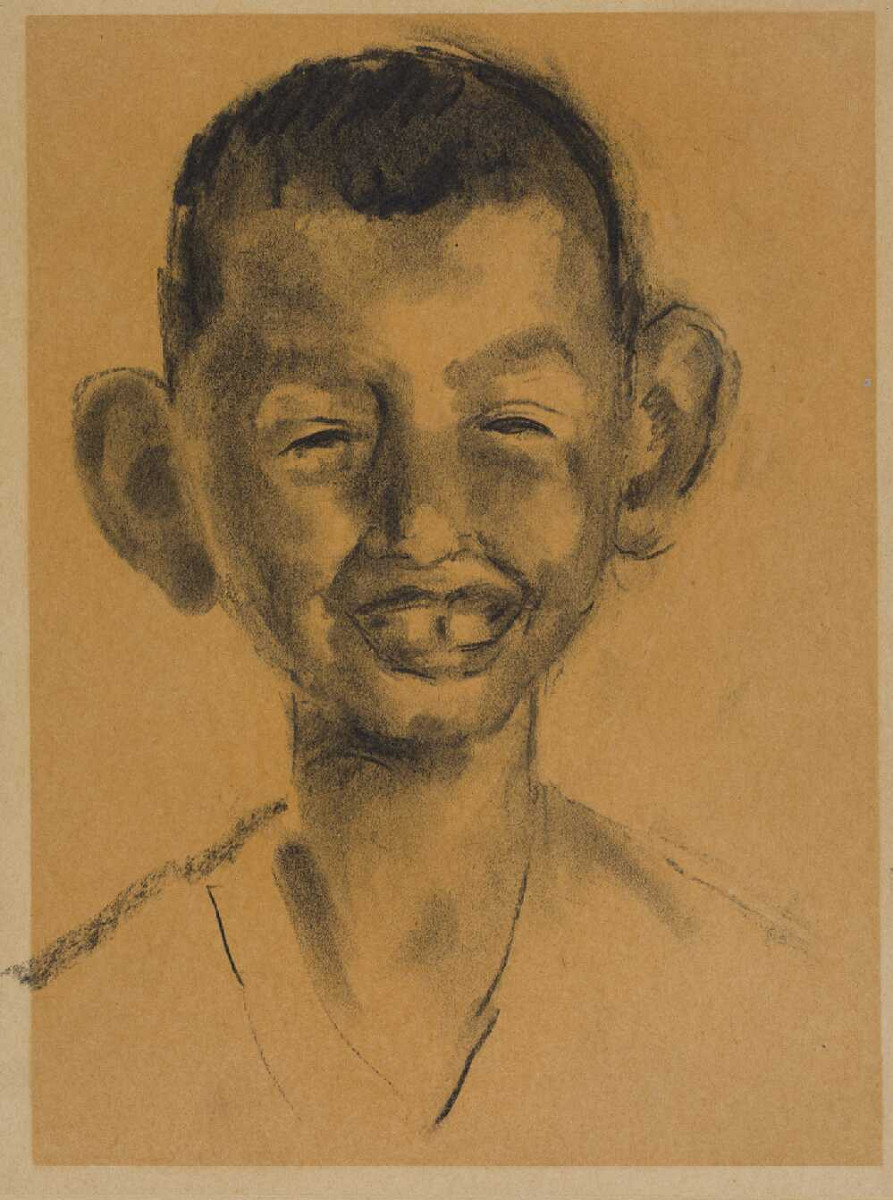

Gela was linked with the Association of Jewish Journalists and Writers, which was reflected in portraits painted at that time. In 1935, Józef Sandel (1894–1962), art historian and art dealer, met het at the Association office at 13 Tłomackie street. He recalled her in these words: To paint – that was her only desire. […] Development of her talent was constantly hampered by difficult living conditions, but she never gave up hope for reaching her aims. She had a particular preference for drawing children. She loved children and could bring out the beauty of each of them. She was living, relaxing, rejoicing while painting a Jewish child. [5]

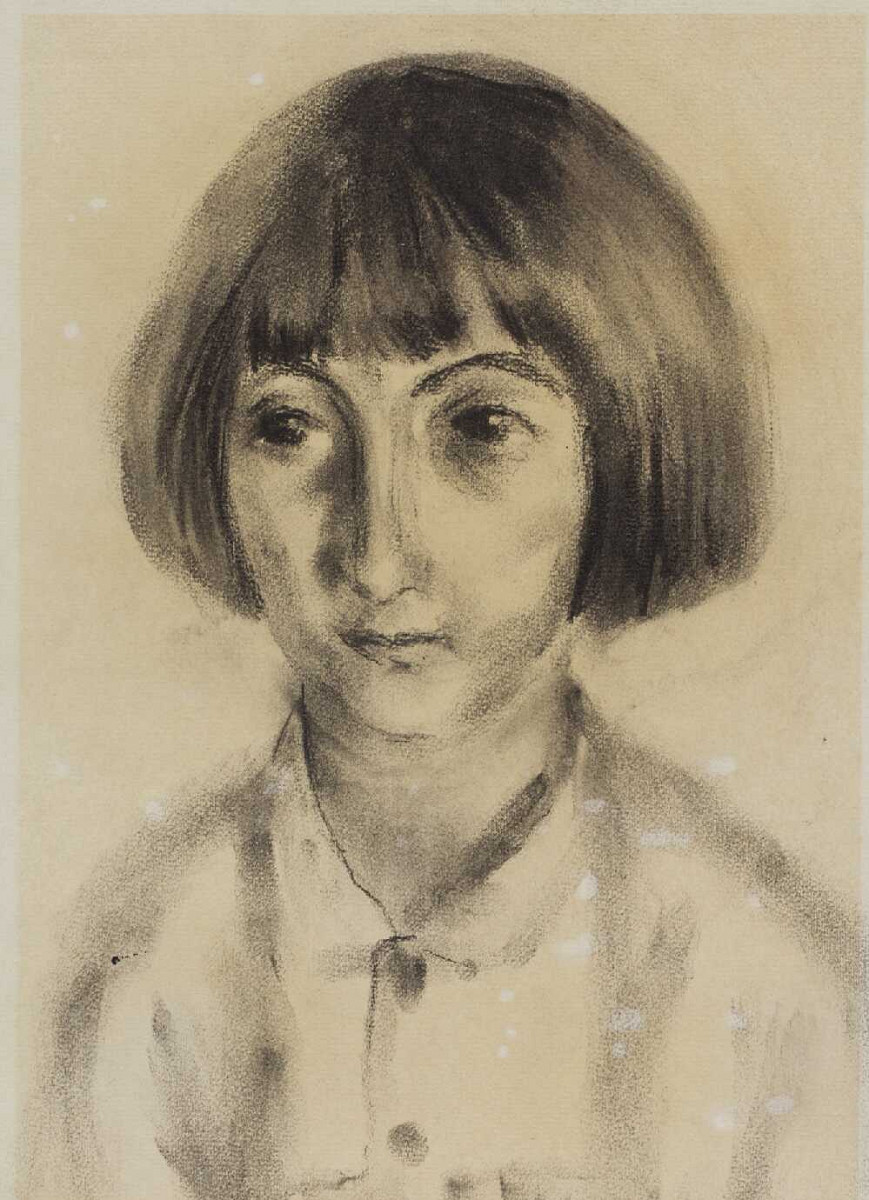

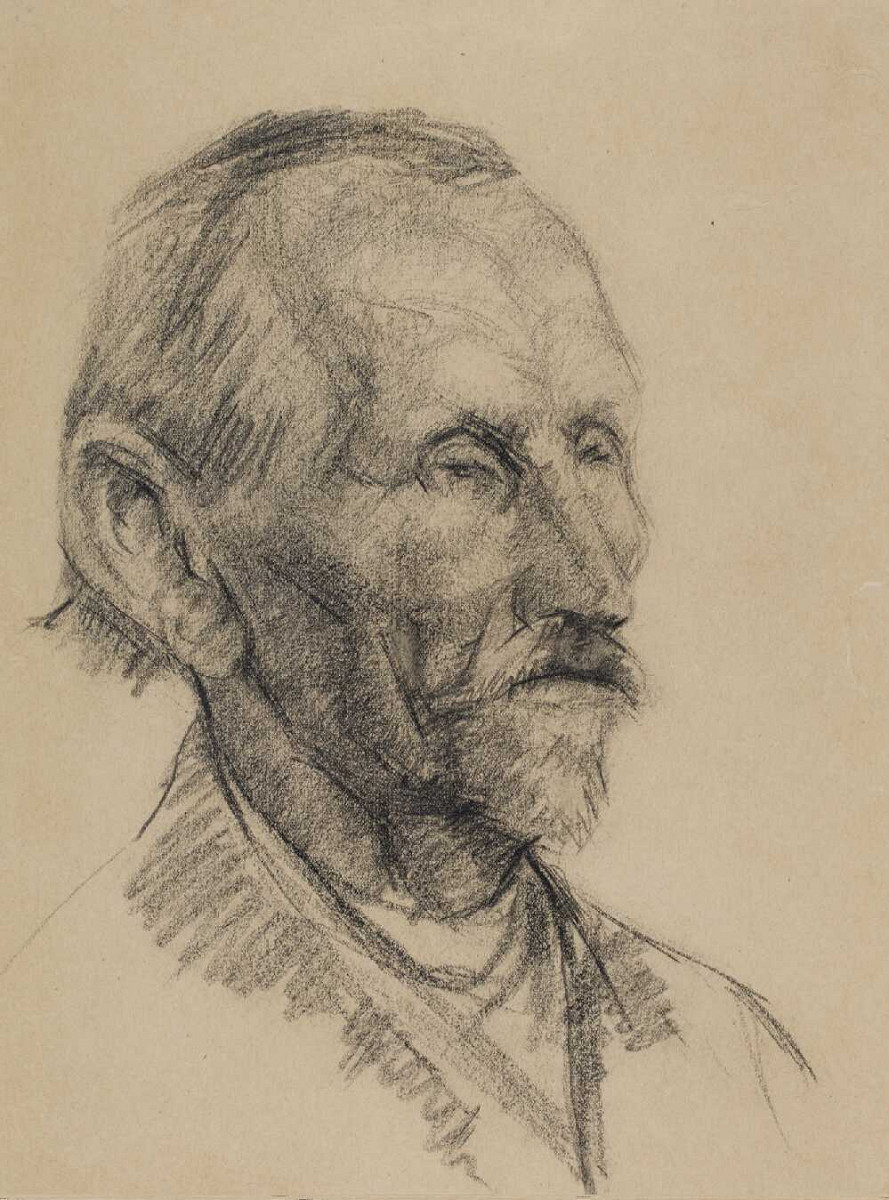

People, adults and children alike, were the main focus of her art. She could convey not only face features in only a few lines, but also the unique, special personality of every person. [6] She painted also still life, landscapes, nudes. Her favourite techniques were watercolours, less frequently – oil, and in drawing – crayons, pencil, ink.

She was presenting her artworks in Warsaw at the Salon of Jewish Society of Popularization of Arts and the Association of Jewish Visual Artists in Poland. In 1931, she took part in the Charity Salon of the Jewish Society of Popularization of Arts opened on 8 November, and one year later – the Winter Salon. Her works were included at the big exhibition of the JSPA in 1933.

Izrael continued his activity in the Poalej Syjon-Lewica party, since 1933, he had been employed at the Common School at 16 Muranowska street. Thanks to his support, Gela was finding employment in Jewish schools and accompanied her husband at summer camps, where she was teaching drawing and handcraft to children.

In the late 1930s, she had her own atelier. In 1938, she participated in two exhibitions, she also presented three paintings at an exhibition organized to celebrate the 5th exhibition of the JSPA. In the same year, she submitted several paintings to the ’Jewish Artists’ exhibition in Paris.

When the war broke out and the ghetto was established, she was engaged along with her husband in the cultural life of the Warsaw Ghetto and in the Jewish Social Self-help. She worked as a guardian and art teacher in charity kitchens for children at the TOZ and CENTOS organizations, and as a teacher in community schools. She was organizing exhibitions of childrens’ artworks and made costumes and decorations for theatre shows.

In the last period of her life, work with children was a priority for her. She didn’t cease to created, but she avoided documenting the tragedy which affected the people of the ghetto – she moved towards life. [7] She was painting children who were coming to the social kitchen, her daughter, her husband, employees of the school. Her only self-portrait was made at that time.

When the Great Deportation began, Emanuel Ringelblum decided to hide gathered materials. He assigned the task to Izrael Lichtensztajn, who gave one box to Gela. She had to make a difficult choice – to select the works which were supposed to survive the war.

Gela’s last sign of life was a letter from 22 September 1942, written by her to Hirszel, one of the managers of Berhnard Hallmann’s workshop. She asked for a job at the workshop. The letter which was preserved in the Archive contains a handwritten note from Izrael: Nothing came out of it!... There’s no understanding.

Gela, Izrael and their daughter Margolit were hiding in one of the buildings belonging to the Hallmann’s workshop. Ringelblum saw Lichtensztajn for the last time on 17 April. The entire family died probably during the first days of the Ghetto Uprising.

Izrael Lichtensztajn, My testament

I would like my wife Gela Seksztajn to be remembered. She was a talented painter, whose dozens of works were not exhibited, they didn’t see the light of day. During the three years of war, she had been working with children as a guardian and a teacher. She was making decorations, costumes for childrens’ theatre plays, she was receiving awards. Now, we are expecting death. [8] (translated by Olga Drenda)

The collection of Gela Seksztajn’s works comprises watercolours, pencil drawings, ink, black crayon, copying pencil drawings. Watercolours larger than the box were rolled. She was painting on grey paper, on thin tissue paper, thick drawing paper.

Many of these works are portraits and studies of people, often with props. They are distinguished by sparse means of expression. They are painted with large, unified spots of colour (…) compositions often are painted without deep perspective. [9] The artist was usually making a pencil sketch, followed by paint. Children were her favourite subject, as well as relationships between parents and children. She wanted to organize an individual exhibition, „The Jewish Child”, but it didn’t happen due to the outbreak of war. Most of the portraits from the Ringelblum Archive were made in the second half of the 1930s, during the summer holiday camps in Kazimierz Dolny nad Wisłą.

The box contains Gela’s testament and her autobiography, Cóż mogę w takiej chwili powiedzieć i czego żądać? (What can I say and demand in a moment like this?), Izrael Lichtensztajn’s testament and his account of the Great Deportation, press cuts about Gela Seksztajn (1931–39), four exhibition catalogues, and 309 artworks (61 watercolours, 178 sketches, 71 drawings), photographs and photo negatives. Only 2 photographs were preserved.

Józef Sandel recalled opening of the box when the first part of the Archive was unearthed in 1946: they were in miserable condition, completely soaked. I was taking out one painting after another, carefully, and attached each of them to the floor. It had to be done quickly, because wet paper was shrinking and sticking together. [10]

Gela Seksztajn, What can I say and demand in a moment like this?

Standing at the border between life and death, quite certain that I will die, I would like to bid farewell to my friends and to my artworks (…) I don’t ask for praise, only for preserving memory about me and my daughter. (…) I am calm now. I have to die, but I have done my job. I would like the memory about my paintings to remain. Goodbye, friends and colleagues, goodbye, Jewish nation! Don’t let destruction like this happen again.

1 August 1942 [11] (translated by Olga Drenda)

----------------------

The permanent exhibition, What we were unable to shout out to the world, contains original photograph of Gela Seksztajn, a fragment of her testament, her drawing — A sleeping girl, and a fragment of Izrael Lichtensztajn’s testament.

All Gela Seksztajn’s works are printed in the 4. Volume of the Ringelblum Archive.

Footnotes:

[1] Gela Seksztajn, Parę lat z mojego życia [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn, Vol. 4, ed. Magdalena Tarnowska, p. 23.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Magdalena Tarnowska, Życie Geli Seksztajn [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn, Vol. 4, ed. Magdalena Tarnowska, p.XXV.

[4] Gela Seksztajn, Parę lat z mojego życia, p. 23.

[5] Malarze żydowscy w getcie warszawskim, [in:] „Nasze Słowo” 1948, nr 6–7.

[6] Magdalena Tarnowska, Życie Geli Seksztajn, p. XXII.

[7] Ibidem, p. XXXVI.

[8] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn, Vol. 4, ed. Magdalena Tarnowska, p. 14.

[9] Magdalena Tarnowska, Życie Geli Seksztajn, p. XLIII.

[10] Ibidem, p. LIII.

[11] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn, op. cit., p. 19.

Bibliography:

Archiwum Ringelbluma. Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn, Vol. 4, ed. Magdalena Tarnowska.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, transl. Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, JHI, Warsaw 2017.