- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

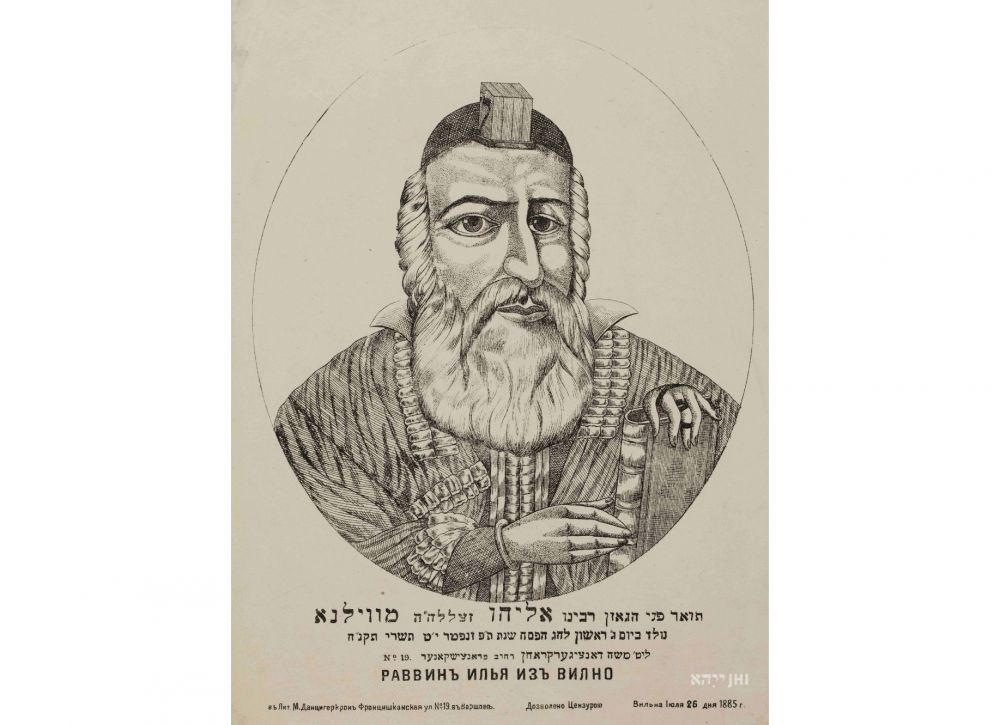

The Vilna Gaon’s image, a litograph, publ. by M. Dancigerkron, Warsaw 1885. JHI collection

In Judaism, an adult male Jew has the absolute obligation to obey the 613 commandments (mitzvot) [however, until the Holy Temple will be rebuilt, there are a number of mitzvot that cannot be done]. Their source is G-d Himself. They were given to Moses (as the Torah: teaching, instruction, G-d’s Word), in writing (the Pentateuch) and orally (the development of the oral Torah is the Mishnah and Gemara, which make up the Talmud). An expression of observing the mitzvot is an incessant study of the Torah, to live according to it, without ever veering off the chosen path. (…) The role of a Jewish man is to learn the Torah, to observe the commandments and to guide his entire household – wife, children and others under his care – to observe them, too. [1]

Elijah ben Shlomo Zalman, known later as the Vilna Gaon, had these principles instilled within him from childhood. He was born in 1720 in Sielec, today’s Belarus. As a child, he spent all his time studying – not in a cheder, like most boys, but under the watchful eye of his father, a rabbi. As a 7-year-old, he gave his first lecture on the Talmud.

![gaon_kto_eibeschutz_comp_cut_zw_2.jpg [1,008.78 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/10/26/e5b270bcf487c9e9144d0b05795e6c81/jpg/jhi/preview/gaon_kto_eibeschutz_comp_cut_zw_2.jpg)

When he matured, it was said that he slept for no more than two hours a night, sometimes adding short naps during the day. He is always portrayed as wearing tefillin in his images from the epoch, symbolising total dedication to study and prayer. “It was said that he spent nights in an unheated room with his feet in a bowl of cold water so as not to fall asleep” [2]. During his brief imprisonment by the tsarist authorities for taking part in the kidnapping of a convert, which was during the Sukkot holiday, a time where Jews sleep in huts, it was said that “during the whole week of the holiday he walked back and forth around his cell, having his eyes open so as not to sleep in the wrong place” [3].

Customarily, famous rabbis and scholars were simply called rabbi, a teacher. The term gaon, meaning “genius”, was reserved only for the most eminent masters and was rarely used after the 6th century, when the Babylonian Talmud was already formed. [4] The Vilna Gaon was one of the few later scholars of the Torah and Talmud, who were deemed classics.

“Gaon” was not a formal title and was not associated with a specific authority, although the rabbis graced with it were often the heads of yeshivas (religious high schools) and, like other rabbis, were judges themselves and had the power to appoint judges [5]. The title emphasised the great authority of the teacher. He had the right to issue responses, i.e. answers to questions that were directed to sages by the Jewish communities. Those deemed ‘Gaon’ explained the principles of Jewish life to communities that did not have a copy of the Talmud or found no interpretation of a specific issue in it. The Gaon’s opinion was crucial to the Jewish community in its daily difficulties and during theological disputes. However, the Vilna Gaon even avoided issuing responses; this was proof of his secretiveness and reluctance to leave his world of books. None of his works were published during his lifetime; it was only his sons and disciples who published them after his death.

![szneur_zalman_comp_zw_2.jpg [798.47 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/10/26/c97defe0d18efdc66ff14014693680fd/jpg/jhi/preview/szneur_zalman_comp_zw_2.jpg)

One of the few times the Vilna Gaon spoke was the case of Jonathan Eibeschütz. In 1750, this rabbi from Kraków, working in the Czech Republic, France, and Germany, former head of the most famous European yeshiva in Prague, was openly accused of believing in Sabbataism (a heresy according to which the messiah was Shabbetai Tzvi) by Rabbi Yaakov Emden. The dispute went on for many years and involved Jewish communities all over Europe. Eibeschütz asked the Vilna Gaon (as well as 49 other rabbis) for their opinion, although Elijah was only 35 and the time and Eibeschütz was 65. This proves the exceptional authority of the rabbi from Vilnius at an early age.

The scholar from Vilnius didn’t lead a peaceful life. Not because of the last lingering Sabbataism. In his time, in the eastern territories of the Commonwealth, a new movement within Judaism was born – Hasidism. It was started by Rabbi Baal Shem Tov, and was continued by his students, such as Shneur Zalman of Liadi (the founder and first Rebbe of the Chabad Hasidic dynasty), and Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk. The community authorities were afraid of religious groups over which they had no control, and the Gaon – the advocate of knowledge – opposed Hasidism because they focused solely on prayer [6]. He himself strove for a model of piety that combined knowledge with prayer, erudition with the fear of G-d.

Footnotes:

[1] Monika Krawczyk, Gaon z Wilna jako osobowość religijna i osobistość historyczna, w: Ukryte oblicze. Gaon z Wilna/Hidden Image. Vilna Gaon [The Vilna Gaon as a religious and historical personality, in: Hidden Image. Vilna Gaon] brochure for the temporary exhibition at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw 2021, pp. 9-10.

[2] Harry Freedman, Talmud. Biografia [The Talmud A Biography], transl. Aleksandra Czwojdrak, Kraków 2015, p. 188.

[3] Ibid., p. 191.

[4] General information about Gaonim taken from the entry: Rafał Żebrowski, Gaon, Polski Słownik Judaistyczny online, https://delet.jhi.pl/pl/psj?articleId=14820, access 26.10.2021.

[5] Gaon, Jewish Virtual Encyklopedia, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/gaon, access 26.10.2021.

[6] M. Krawczyk, op. cit., p. 19.