- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

She was born on 19 June 1909 in Warsaw, the daughter of Maksymilian and Bluma Łazowert. Her mother was a teacher. After graduating from Narcyza Żmichowska Middle School, she studied Polish and Romance languages at the University of Warsaw as an audit student.

In 1930, she received an award in the literary competition of the University of Warsaw Polish Studies Club for her poem Stara Panna (The Old Maid). After finishing university, she received a scholarship from the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment, which allowed her to study at the University of Grenoble Faculty of Letters. After returning to Warsaw, she began collaborating with the literary magazines Droga and Plon.

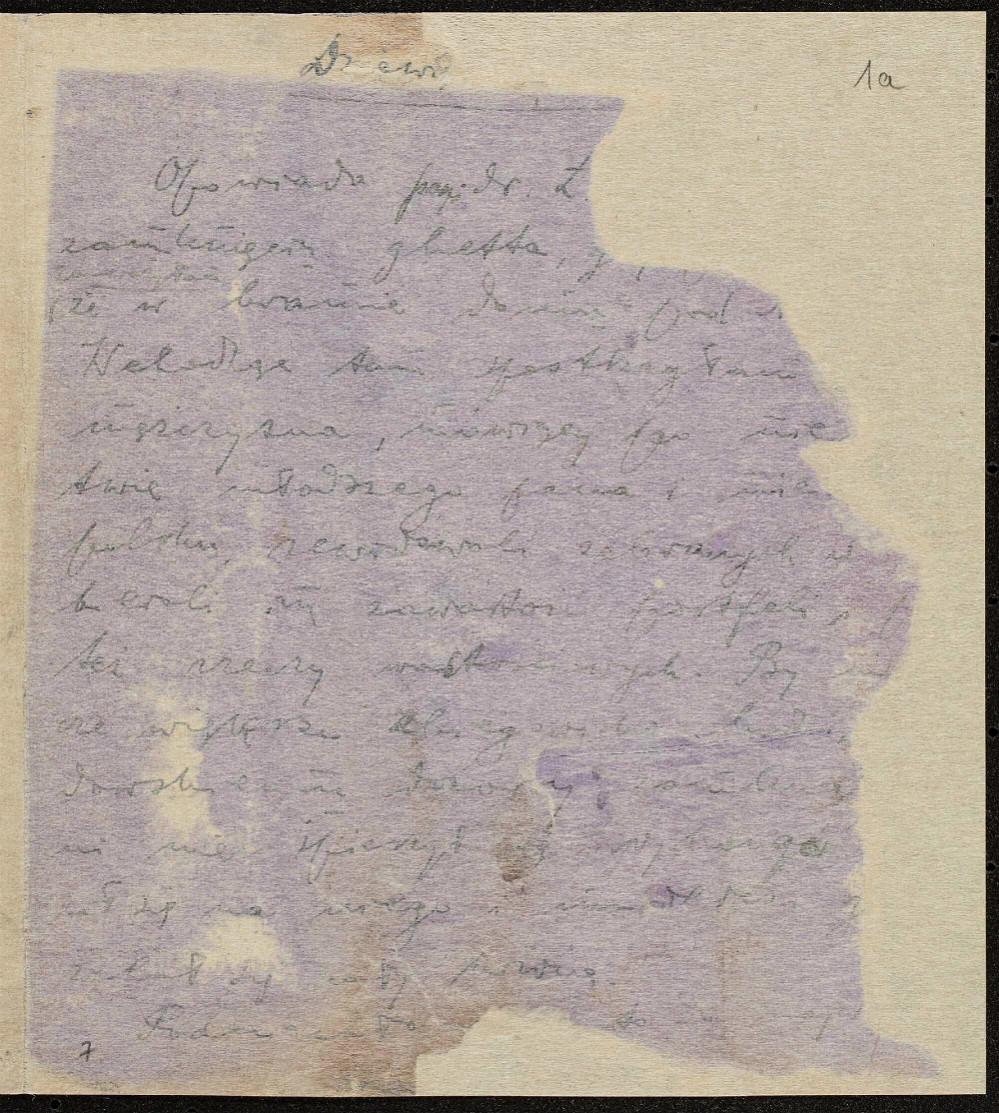

Before the war, she published two very well received volumes of poetry: Zamknięty pokój (Closed Room) (1930) and Imiona Świata (Names of the World) (1934), and in 1938 a short story entitled Wrogowie (Enemies) in Nowy Głos (30 April 1938). In 1935, she became a member of the Warsaw branch of the Union of Polish Writers. She was a passionate book collector.

Before 1939, she lived with her mother on Sienna Street in Warsaw. After the ghetto was established, their building became part of what became known as the Small Ghetto.

After the outbreak of war, Łazowertówna became involved in social work, including in the activities of the charity organization CENTOS, which took care of homeless people and orphaned children. Emanuel Ringelblum, who offered her the job of preparing publicity materials for the Jewish Social Self-Help (she wrote leaflets, appeals and other materials addressed to Jews who only spoke Polish), wrote: Her propaganda materials, posters, appeals, letters, etc. were characterized by a kind, light and simple style. They were effective due to their simplicity and sincerity because the poet wrote them in blood straight from her pained heart, so very sensitive to the terrible suffering of the Jewish masses. [1] Łazowertówna was also one of the leaders of the finance section of the Jewish Social Self-Help. [2]

Ringelblum got Łazowertówna involved in the work of the Oneg Shabbat. She mainly wrote about refugees, distilling the fate of individual Jewish families from statistics and self-help reports and documenting their struggle to survive in the ghetto. She is the author of the account Dziewięć miesięcy na Pawiaku (Nine Months at the Pawiak) from 1941 (available in volume 5 of the Ringelblum Archive: Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne).

She started to write monographs on individual families, which moved readers to tears. She gave one of these to read to social activists who were closely familiar with the life of refugees, but they said that it was only the young writer who had opened their eyes to the terrible tragedy of each of the tens of thousands of refugee families in Warsaw. [3]

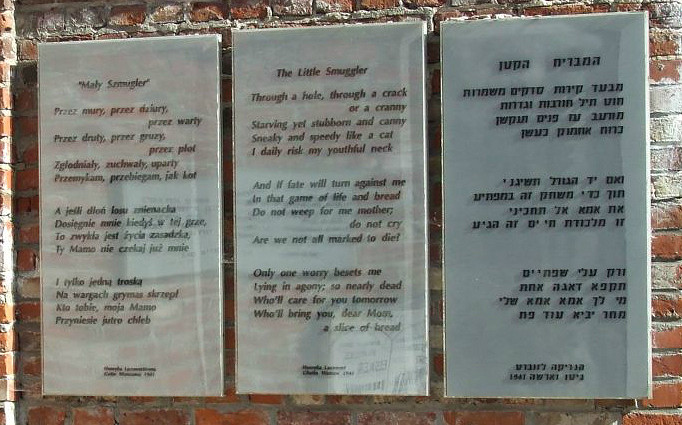

Her monograph about a family from Bydgoszcz resettled to Warsaw won one of the first prizes in a competition organized by the Oneg Shabbat among a small circle of friends and collaborators. [4] The poet was part of literary competition juries, but also read her poems herself at poetry evenings. Her work was extremely popular. The well-known singer Diana Blumenfeld performed a song to the text of Łazowertówna’s most famous poem, Mały szmugler (Little Smuggler), in ghetto restaurants and theatres.

LITTLE SMUGGLER

Past rubble, fence, barbed wire

Past soldiers guarding the Wall,

Starving but still defiant,

I softly steal past them all.

Clutching a bag of sacking,

With only rags to wear,

With limbs numbed by winter,

And hearts numbed by despair.

(Translation sourced from: Richard C. Lukas, Did the Children Cry?: Hitler’s War against Jewish and Polish Children, 1939–1945, New York 1994)

Emanuel Ringelblum, who devoted an extensive note to Łazowertówna in his writings from the bunker, recalled: The poet wrote a lot, really a lot. She wrote poems on current topics. (…) Her poem about the little smuggler recited at assemblies and literary evening, made a great impression on everyone. [4]

Łazowertówna suffered from an illness of the lungs. From spring 1940 she tried to leave Warsaw and move to Kraków with her mother, but this proved impossible due to insufficient financial resources. Friends proposed to hide her on the Aryan side, but she reportedly refused, explaining that she was needed by the CENTOS children.

Ringelblum wrote: Łazowertówna had a lung disease, but without a lot of cash, without some ten thousand zlotys, it was futile to dream of the Aryan side. Łazowertówna had many Polish friends (…) yet no one stepped forward to save her. During the first deportation she perished in Treblinka with her mother. (…) At the Umschlagplatz, they tried to save her from going into the train car, but they did not want to or could not release her mother. Henryka Łazowertówna was well aware that deportation meant death, but she followed her mother anyway. [5]

A poem that she wrote in 1934 seems eerily prophetic…

DREAM

A dream like this: I am going away alone, somewhere far —

to an unfamiliar station that’s not on any map.

The sky hangs over this station like a great black lid,

The locomotive screams with the voice of a beaten man,

the railwaymen have faces like paper…

I have a single suitcase with me and a single regret, which no one’s tried to understand…

I am very calm — and, what can’t be seen: very sad.

The flickering city has disappeared behind me, the steam whirls over me —

I am standing in the train car window like a still puppet in a box. [9]

(translated by Dominika Gajewska)

Footnotes:

[1] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Vol. 29a, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, ŻIH, Warszawa 2018, p. 205–206.

[2] Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017, p. 220.

[3] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Vol. 29a, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, op. cit., p. 206.

[4] Ibidem.

[5] Ibidem.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] https://pl.wikisource.org/wiki/Sen_(%C5%81azowert%C3%B3wna)

Bibliography:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Vol. 5, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, ed. Katarzyna Person, ŻIH, Warszawa 2011.

Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017, p. 220.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Vol. 29a, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, ŻIH, Warszawa 2018