- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

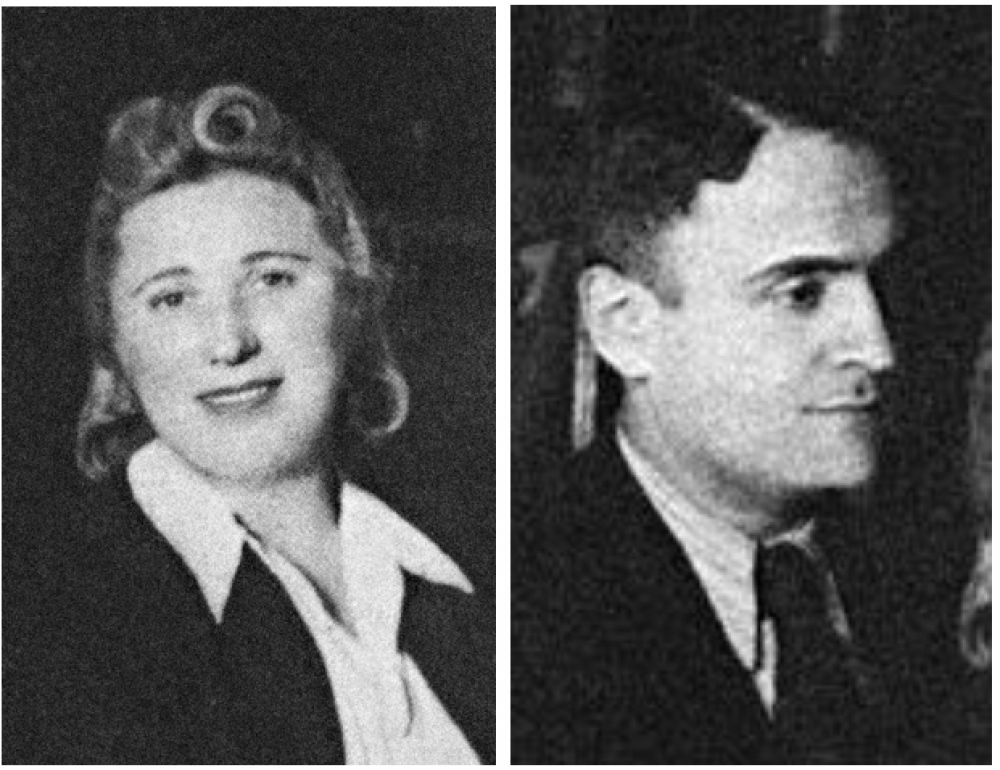

Bluma and Hersz Wasser

Hersz Wasser, son of Lejb and Esther née Podlaska, was born on 13 June 1910 in Suwałki. In 1929, he graduated from the Laor High School, and in 1932 from the Warsaw School of Economics. After graduation, he moved to Łódź, where he worked as an accountant. An activist of Poale Zion Left, he also managed the Ber Borochow party library in Łódź, and from 1934 served as the secretary of the economic and statistical section of the YIVO Institute in Łódź for five years. In December 1939, Wasser married Bluma (née Kirszenfeld) and they moved to Warsaw together.

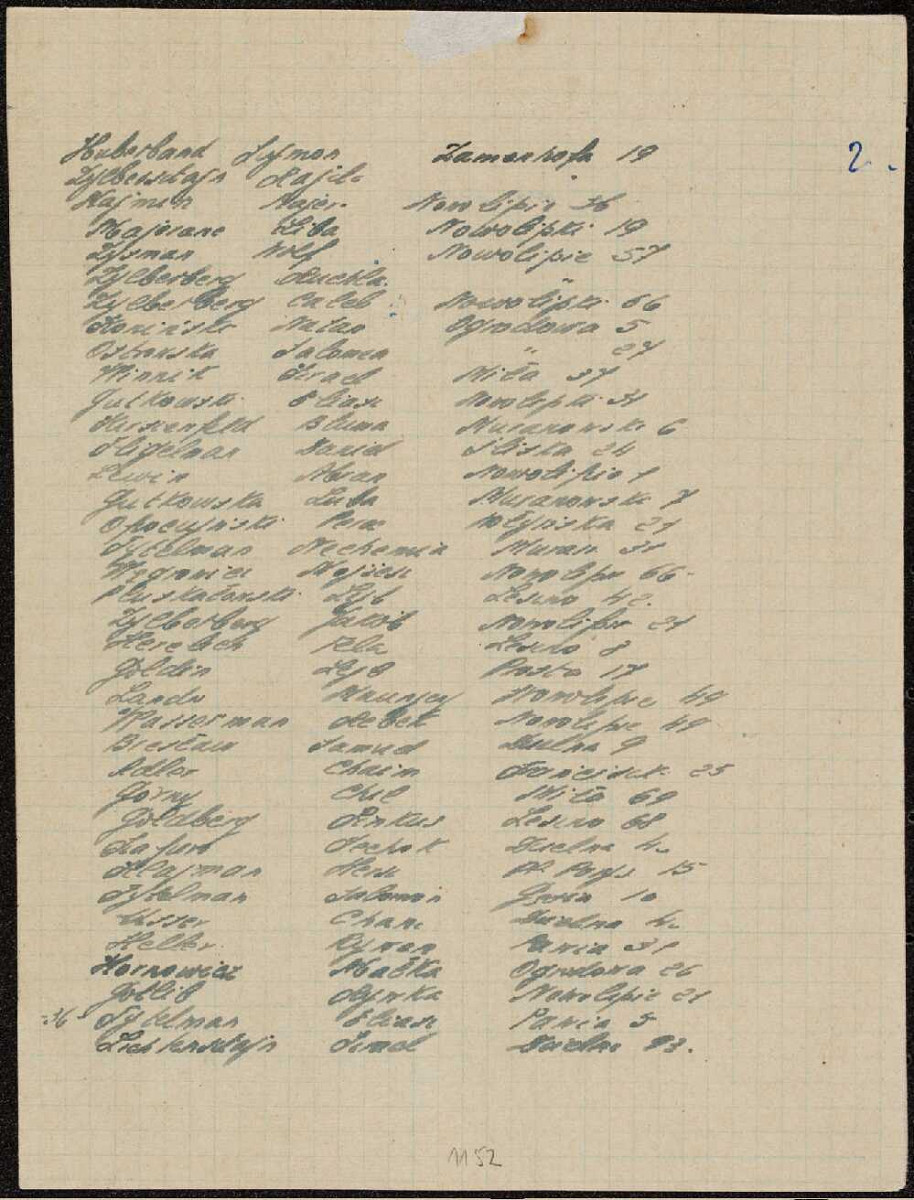

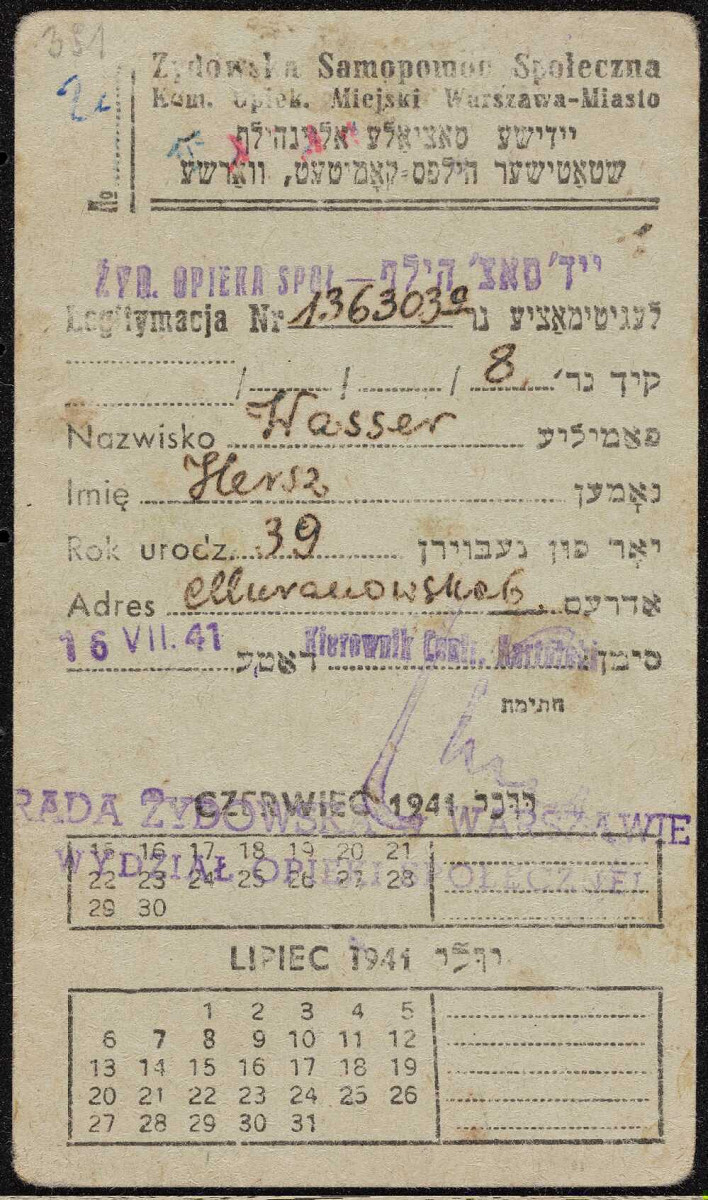

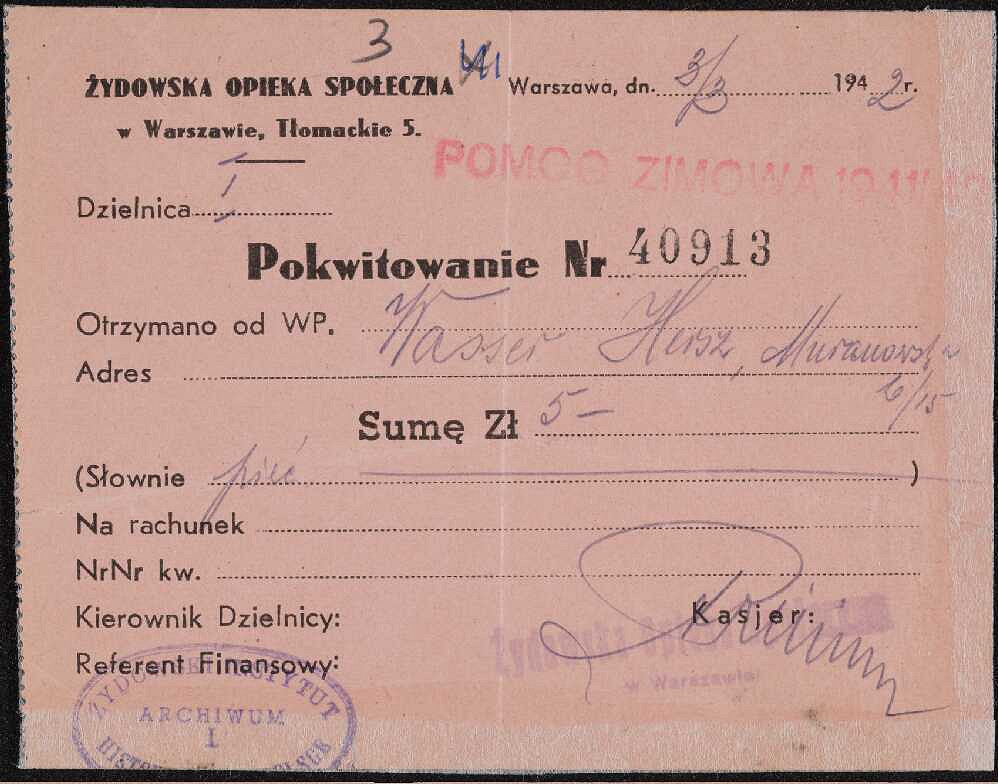

Six months later, he became secretary of the Oneg Shabbat (Eliasz Gutkowski was second secretary). He handled everyday matters: acquiring and cataloguing documents, recruiting and maintaining lists of employees, buying stationery, etc. He also managed the organization’s finances. Small sums of money were distributed through him, perhaps to people with whom interviews were conducted and whose accounts were taken down. Together with Ringelblum and Gutkowski, he prepared research plans, outlines and questionnaires, and after the Great Deportation, the Oneg Shabbat bulletins and reports to be sent abroad. According to the sources, it was Wasser who took the materials to be hidden to the basement of the Ber Borochow school at 68 Nowolipki Street. Thanks to this, he knew where the Archive was hidden and could oversee its extraction after the war.

Ringelblum wrote in his diary about Wasser: Colleague Hersz Wasser was appointed the Oneg Shabbat secretary by the executive body, and still holds this position today. Colleague W., himself a refugee from Łódź, had gained an understanding necessary for this kind of work thanks to his social and political activity. His daily contacts with hundreds of refugee delegations from all parts of the country have allowed him to create hundreds of monographs on cities, which are the Oneg Shabbat’s most precious treasure. [2]

In January 1941, Wasser became secretary of the Central Refugee Commission, an association of the Landmanshafts bringing together Jewish refugees in Warsaw. He collected their accounts and letters for the Archive. This work was of great value to the Oneg Shabbat, providing crucial information about the fate of Jews in the countryside. Hersz involved his wife, who worked in Warsaw as a teacher, in these underground activities, too. She conducted interviews, copied documents and accounts in Yiddish (including the accounts of the first escapees from the extermination camps in Chełmno, including the account of Szlama Ber Winer, and Treblinka) and catalogued the collections.

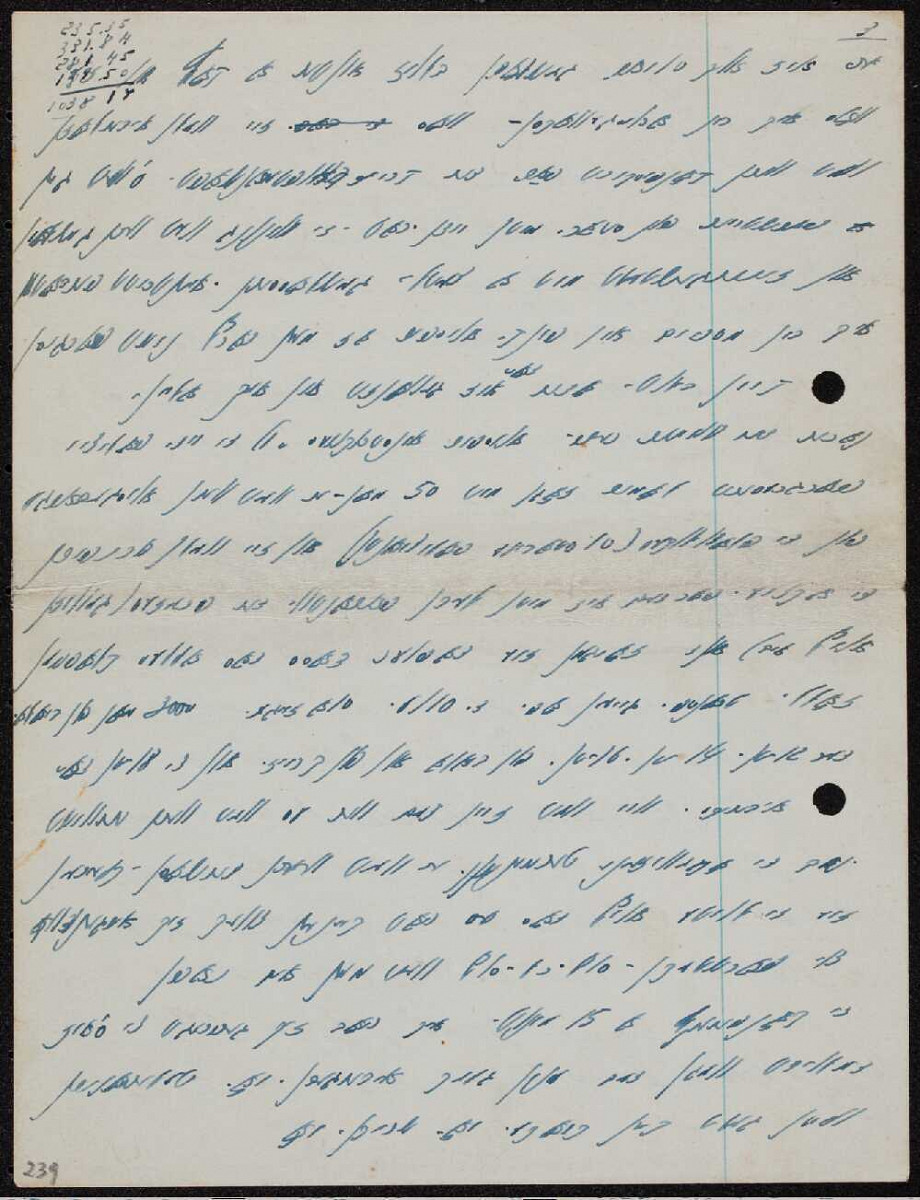

Hersz also kept a diary from 1 December 1940 until 10 July 1942, in which he scrupulously, albeit sparingly, recorded events and the moods prevailing in the ghetto. He also described the Oneg Shabbat meetings. Unfortunately, there are few personal accents: One feels no desire to write about oneself. I’m just happy that the day passes with active social work. [3]

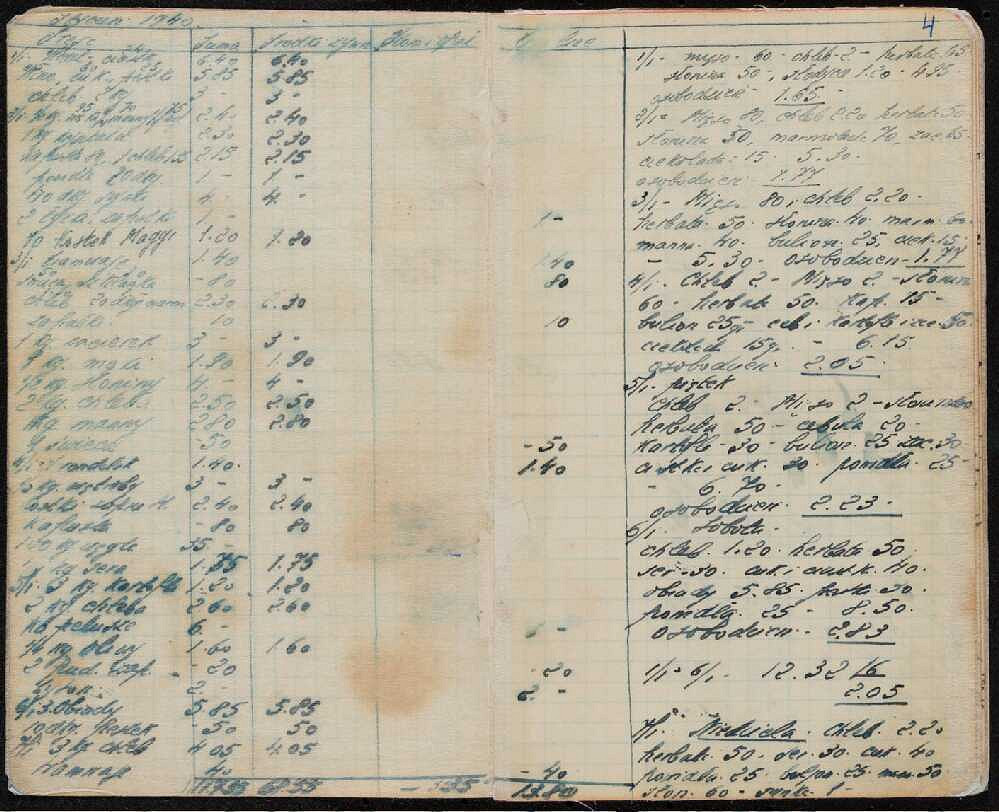

However, the Wassers’ book of household expenses – an extremely interesting document that sheds light on the problems of everyday life in the ghetto – has survived. Scrupulously kept during the first year and a half of their stay in Warsaw, it depicts the everyday life of a young couple who are trying to get by in completely new conditions. Aside from beetroot, bread and potatoes, the Wassers mention moving, sickness expenses, bribes, and small amounts of money spent on cosmetics or a visit to the hairdresser. However, the most important strain on their budget are ‘loans’ – sums recorded along with the names of family members confined in ghettos in other towns and cities. [6]

Apart from working for the Oneg Shabbat, Wasser was also active in Poale Zion Left. According to his daughter, Leah Wasser, he was deeply committed to his party. He helped publish underground bulletins and was a member of the Central Committee. In the second half of 1942, he represented the party at several important meetings devoted to the establishment of the Jewish Fighting Organization. He was therefore one of several links that connected the Jewish resistance movement with the Oneg Shabbat. [7]

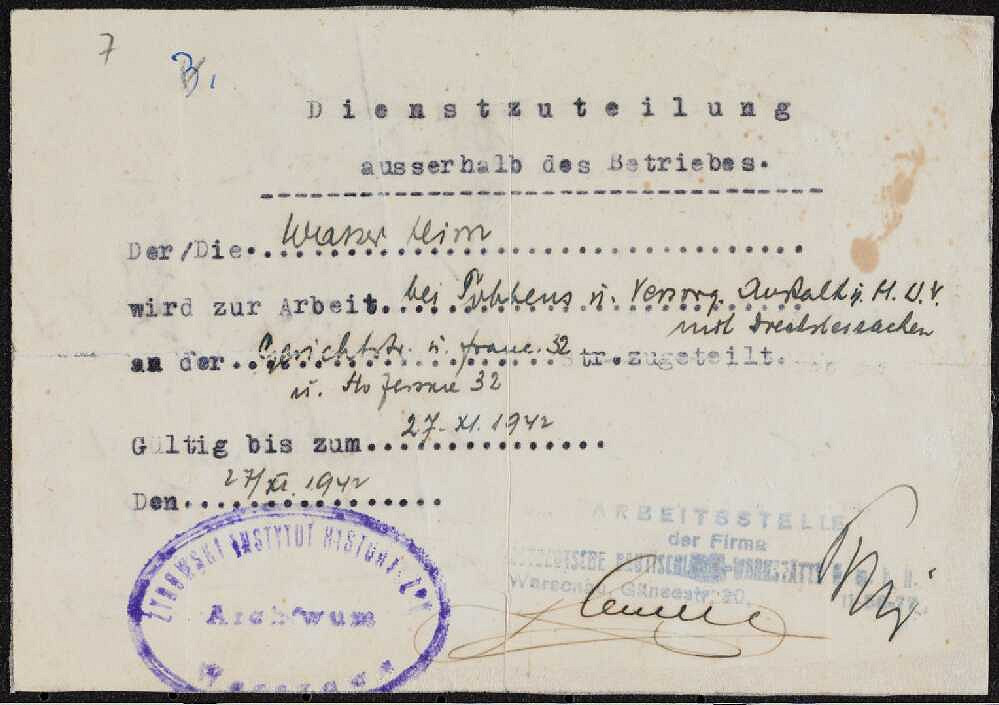

In the summer of 1942, he began working at the Ostdeutsche Bautischlerei-Werkstätte, a carpentry ‘shop’ run by Aleksander Landau. This, however, failed to protect his wife. On 8 August 1942, Bluma Wasser was taken to the Umschlagplatz, but managed to escape. The Wassers crossed over to the ‘Aryan’ side at the beginning of 1943.

Having left the ghetto, Wasser still felt a duty to document the fate of Jews and to continue the work of the Oneg Shabbat. He collected, copied and stored materials commissioned from other Jews in hiding. He also wrote his own essays on topics including the functioning of the ghetto workshops and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, some of which were forwarded to London by the Jewish National Committee through the communication channels of the Government Delegation for Poland.

In April 1943, during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Hersz Wasser escaped from a transport headed for the labor camp in Trawniki, and then hid with his wife in Warsaw (as Henryk and Halina Wodnicki). They survived the Warsaw Uprising in a bunker on Suwalska Street. They shared their hiding place with Hersz Berliński, former commander of the Poale Zion Left combat groups in the ghetto, and the party activists Pola Elster and Eliahu Erlich. The bunker was discovered by the Germans on 26 September 1944. In the shooting that ensued, only the Wassers survived. [8]

They managed to leave Warsaw and lived to see liberation in the village of Łętownia in Małopolska. Of Ringelblum’s collaborators, only they and Rachel Auerbach survived, and of the three, only Hersz Wasser knew where the Archive was hidden.

After the war, Wasser was active in rebuilding Jewish life in Poland. He was a member of the board of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland, the head of the Warsaw branch of the Central Jewish Historical Commission, and the chairman of the Emigration and Landsmanshaft departments of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland. He was elected to the Warsaw National Council as a representative of Poale Zion Left. He conducted research on Poles hiding Jews and prepared expert opinions for the trials of war criminals. As of 1946, he was a lecturer and head of research on the history of the Holocaust in Poland for YIVO. He made a number of attempts to move to the United States. While waiting to leave, he was an intermediary in the transfer of money and materials for the Jewish community in Poland.

But most of all, he fought to find the Archives. He was the only survivor who knew the exact place where the Archives had been hidden, and he brought about the unearthing of the first part from the ruins of the ghetto. While verifying the content of the documents, he left handwritten notes which later helped researchers identify the documents. In 1947, fearing for the future of the Archive, he secretly sent over 200 documents to the YIVO in New York, including the account of Szlama Ber Winer from the extermination camp in Chełmno and the report Gehenna Żydów polskich pod okupacją hitlerowską (The Gehenna of Polish Jews under Nazi occupation). The documents were sent by registered mail to the director of the YIVO Max Weinreich or the YIVO secretary Mark Uveleer.

As Dr. Katarzyna Person writes, today we cannot tell what Wasser’s motivation was for taking on the extremely complex and risky task of sending documents to the United States. He wrote to YIVO that he considered it a ‘sacred task’ and a ‘national mission’. [9] He believed they would be safe there. Perhaps in his opinion Ringelblum himself would have liked to see them there because of his relationship with the YIVO. [10] The documents never returned to Poland. They were published in the 14th volume of the Ringelblum Archive edited by Katarzyna Person, titled Hersz Wasser’s Collection (in Polish).

In 1950, the Wassers ultimately left for Israel. Hersz became the director of the Emanuel Ringelblum Institute for Research on the Jewish Workers’ Movement, which he founded in Tel Aviv, and later the director of the J.L. Peretz publishing house. He died in 1980. Bluma Wasser died ten years after her husband.

Footnotes:

[1] Hersz Wasser, Diary [in:] The Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 14. Hersz Wasser’s Collection, ed. Katarzyna Person, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warsaw 2014, p. 12.

[2] The Ringelblum Archive, vol. 29, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2018, p. 497.

[3] Hersz Wasser, Diary, op. cit., p. 3.

[4] Ibidem, p. 22.

[5] Ibidem, p. 53.

[6] Katarzyna Person, Intoduction [in:] The Ringelblum Archive, vol. 7, Spuścizny, ed. Katarzyna Person, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warsaw 2012, p. XVII.

[7] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2017, p. 271.

[8] Ibidem, p. 271–272.

[9] Katarzyna Person, Hersz Wasser. Sekretarz Archiwum, Zagłada Żydów, nr. 10, Warszawa 2014, p. 302.

[10] Ibidem, p. 303.

Bibliography:

Katarzyna Person, Hersz Wasser. Sekretarz Archiwum. Zagłada Żydów, nr. 10, Warszawa 2014.

Katarzyna Person, Introduction [in:] The Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 14. Kolekcja Hersza Wassera, ed. Katarzyna Person, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2014.

The Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 7, Spuścizny, ed. Katarzyna Person, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2012.

The Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 11, Ludzie Oneg Szabat, ed. Aleksandra Bańkowska, Tadeusz Epsztein, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2013.

The Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 29, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2018.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017.

Basia Temkin-Bermanowa, Dziennik z podziemia, ŻIH, Twój Styl, Warszawa 2000.