Bernard (Berisz) Kampelmacher was born in 1889 in Stanisławów (today Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine). During World War I, he fought in the Austrian Army and received officer’s ranks. After the war, he became a teacher employed at the Common School in Sochaczew, a town without any Jewish cultural organizations. Kampelmacher decided to establish a sports club. In order to raise the money, he founded a choir, whose rehearsals were held in a room he rented. The first concert, to celebrate Pesach, took place in the hall of a defunct Jewish school. Raised money was spent to buy a ball (among others). [1]

The first attempts to play took place at the city market, today – the Defenders of Sochaczew Square. It turned out that nobody, including Kampelmacher, knows the rules of the game. The first coach was a student and member of one of the Warsaw teams, Kowa Gutein, whom he invited to Sochaczew. On 3 February 1925, the Jewish Sports and Gymnastics Society was placed on a registry of associations. Soon, they began to expand their offer – including handball, table tennis, gymnastics, boxing, chess, non-professional photography and tourist trips. Kampelmacher was also organizing evening dance meetings on holidays such as Purim and Hanukkah, but also without occasion (such as the Dance Evening with the Warsaw Jazz Orchestra). The Sports Club had their own accommodation, and the team began to wear uniformed outifits – tops with black and white stripes, and emblem saying „Tourism and Sports Club” in Yiddish, and Polish letters Z.G.T. He began to visit other cities, where he played matches against other teams, such as „Strzelec” or „Sokół”. The last enterprise Kampelmacher participated in was construction of tennis courts outside of the city. The Jewish youth went there with spades and axes and cleaared the ground which was later covered with asphalt. The idea of building a sports hall wasn’t eventually put into practice. [2]

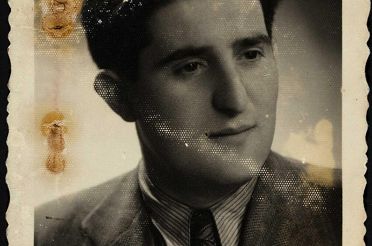

![Kampelmacher_2.jpg [247.90 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/307df265d39684e09bf527e691832a43/jpg/jhi/preview/Kampelmacher_2.jpg)

fter some time, Kampelmacher was moved to Grodzisk Mazowiecki, where he had been working as the principal of the State Common School no. 4 since 1928. He was teaching Polish for Jewish children and organized trips to Żelazowa Wola, where he was giving talks on Chopin. He managed to build a new school, where he also established a children’s sports club and an orchestra. [3] He was also leading the Jewish Department of the Polish Red Cross. We also know that his son died before the war broke out.

For me, the memories of the cemetery in Sochaczew are a wound which won’t heal, because aside from my close friends and students, I have buried there, on the most beautiful provincial Jewish cemetery, my 13-year old son, a student of the nearby gymnasium. A dove with a leaf in a beak, sculpted on the monument cut sharply like his young life, always reminds me of his mild character. [4]

Kampelmacher didn’t give up on his involvement in social activism after September 1939. He became a member of the Jewish Council in Grodzisk (he was leading the council for some time as well) and the president of the Delegation of the Jewish Social Self-Help. When the Jews of Grodzisk were resettled to the Warsaw Ghetto in February 1941, he became the leader of the Grodzisk landsmanshaft.

Emanuel Ringelblum made him an offer to write a monograph of Grodzisk, which Kampelmacher responded to enthusiastically. The Ringelblum Archive contains over a dozen sketches he wrote about the history of the Grodzisk Jewish community, including the history of the synagogue, the cemetery, the mikveh, a chapter on industry and education before the war, a profile of the Jewish Council, and of Jewish collaborators during the war. Kampelmacher also wrote monographs of several locations in the Sochaczew county: Podkowa Leśna, Wiskitki and Sochaczew. He was receiving a symbolic payment for his work.

Samuel D. Kassow notes that a ot of material submitted by him to the Archive proves that he was a diligent, methodical and thorough person. Kampelmacher coped amidst the chaos of the Warsaw Ghetto thanks to self-imposed discipline and love for order. [5]

Kampelmacher was also involved in attempts to improve the critical condition of education in the Warsaw Ghetto. He proposed to organize schools in connection with the home committees, which he described in his project from May 1941, „An attempt to resolve the problems of common education in the Jewish district of the City of Warsaw”

In early 1942, Kampelmacher died due to typhus infection.

![kampelmacher_3.jpg [341.86 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/3c7a8698d0d8e721a545190b4cb8486a/jpg/jhi/preview/kampelmacher_3.jpg)

Ringelblum wrote: Many valuable contributors have died due to typhus. Kampelmacher, principal of the Polish school for Jewish children in Grodzisk, was one of them. Comrade Kampelmacher was one of the most dedicated social activists in Grodzisk. He couldn’t find any work in Warsaw. Only in Oneg Shabbat, he had discovered a right place for himself. He planned to write an extensive monograph about the experiences of the Grodzisk Jews. He began with the situation before the war. The first chapters were lively and interesting. Kampelmacher expressed thankfulness for an opportunity to work with Oneg Shabbat every time he saw me. Now he had a goal in life. He wanted to dedicate himself fully to this noble work. He only regrets that he has lost so much time unaware that this work was being done. While turning his plans into reality, Kampelmacher became infected with typhus during his work as a delegate of his landsmanshaft, and never stood up from his bed again. [6]

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

![kampelmacher_4.jpg [347.36 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/1ed2b5e82bfd991635a3a287d7ca165e/jpg/jhi/preview/kampelmacher_4.jpg)

in the Jewish district of the City of Warsaw / The Ringelblum Archive

Footnotes:

[1] Radosław Jarosiński, Sochaczewscy Żydzi i sport, 11 July 2017, sochaczewianin.pl, https://sochaczewianin.pl/2017/07/11/sochaczewscy-zydzi-i-sport/#.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/g/412-grodzisk-mazowiecki/102-oswiata-i-kultura/26676-oswiata-i-kultura-w-grodzisku-mazowieckim

[4] Bernard Kampelmacher, Sochaczew. Cmentarz żydowski [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Generalne Gubernatorstwo. Relacje i dokumenty, vol 6, ed. Aleksandra Bańkowska, WUW 2012, p. 543.

[5] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. 309.

[6] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018, p. 501.

Bibliografia:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Generalne Gubernatorstwo. Relacje i dokumenty, vol. 6, opr. Aleksandra Bańkowska, WUW 2012.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018.

https://sochaczewianin.pl/2017/07/11/sochaczewscy-zydzi-i-sport/#

![MKiDN_bialy_logotyp_strona_ŻIH_EN.png [10.32 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2023/1/12/0fbb15388d1a5d89c65891b6ce66941c/png/jhi/preview/ZNAK%20ENG.png)