- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

The holidays are over and the new academic year once again has sparked discussions about: activities for children in nursery schools, whether six-year-olds should be sent to school, and changes in the curriculum in high schools and colleges. Therefore, we have decided to recall how the education in the community of Polish Jews was organised.

Children from orthodox families began learning between the age of three and five. Then, their parents enrolled them to cheders — religious elementary schools — where for the first two years they were taught to read and write. The next step was memorising fragments of the Hebrew Bible and translating them into Yiddish. Melodious recitations of sacred texts could be heard through the windows of the school from the morning until the evening prayer.

Cheders were usually located in the house of the teacher, called Melameds. That is where the name of this type of school derives from, in Hebrew meaning „chamber”.

The curriculum at cheders was not controlled by anyone, which did not have a good influence on their level of education. Most melameds and supporting thembelfers (from Yiddish „assistant teacher in cheder”) effectively resisted pressure of the supporters of the Haskalah — the Jewish Renaissance — who since the beginning of the nineteenth century had strived for incorporating secular subjects into the curriculum of religious elementary schools and popularising cheders for girls.

Conditions in which the children had to spend whole days left a lot to be desired. Urke Nachalnik, a professional burglar who while doing sentence in prison was writing down memories of his youth, depicted his stay in cheder at the beginning of the twentieth century in the darkest colors:

We are bent over books and shouting in different voices. In the middle of the cheder, on the dirty, clay floor a few girls are sitting in different poses. They are playing, each in their own way. In the corner of the cheder, in the smoke, it is possible to see a silhouette of Rabbis’s wife, who is grumbling something under her breath about her husband. It is not a big chamber and it is located in the basement. It has never been ventilated. Students, who were constantly filling it, breathed in the smoke and fumes.

The situation began to change significantly when reborn Poland in 1918 introduced compulsory education. An increasing number of cheders introduced the natural sciences, and in 1922 those which were „modernized” were given the status of public schools. The changes in the functioning of religious schools were also undoubtedly influenced by the progressive secularization of the Jewish community. More and more Jews — especially in large cities — chose secular schools, often linked to certain political circles. Many parents decided to send their children to Polish schools which was often a difficult experience for their children:

The very first day in school brought problems,” wrote writer Julian Stryjkowski. „This cross on the wall, and me — godless, bareheaded! Dear God, after all it is a sin! On top of that, the teacher began the lesson with a prayer that the boys repeated after her and I stood with my head lowered as if I was the culprit. [...] I was the only one in the class with sidelocks. Not long ones, but visible. Classmates-Poles would pull my hair. They made fun of me because it was funny to them, and also offensive. I was kind of a victim of an anti-religious lark. I really wanted to have the haircut like the others.

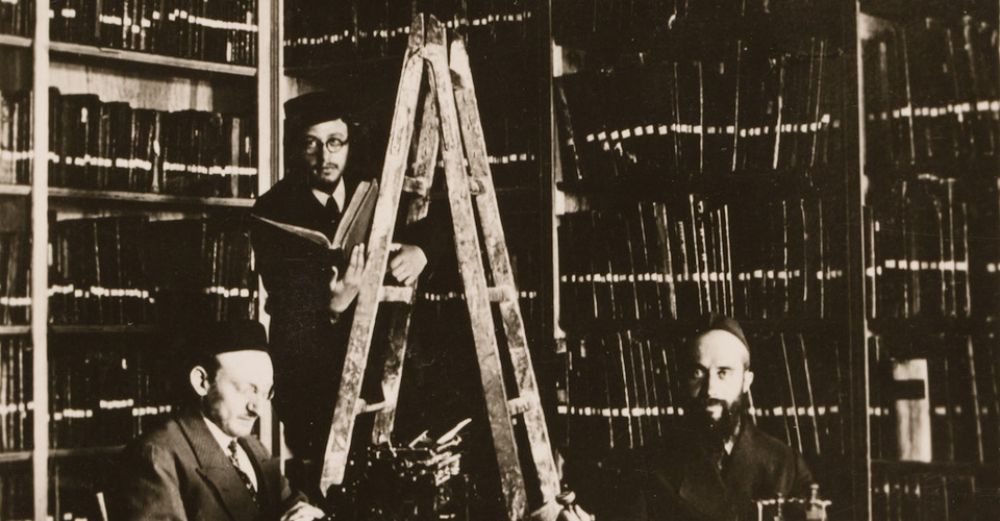

Learning in cheder ended when the students were 13 years old. The most talented of them could continue their education in a yeshiva, or Talmudic schools, educating candidates for rabbis. The first yeshivas on Polish territories were founded at the beginning of the sixteenth century, including famous around Europe yeshiva of Rabbi Shalom Szachna in Lublin, which was granted privileges by Sigismund II Augustus similar to those that Christian academies had. In the next centuries yeshivas operated in every large Jewish community. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries secular sciences already began to be introduced in the curriculum of yeshivas.

In 1930, the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva was opened. Its founder, the first orthodox MP of the Second Polish Republic, Rabbi Meir Shapiro, referring to the tradition of the first Lublin Yeshiva hoped that he could create a global center of Talmudic studies. For the support of his idea, Shapiro successfully strived on both sides of the ocean. The collected contributions were used to build an impressive five-storey building. Lublin school really quickly gained a high international reputation. Shapiro, however, died three years after its opening, and the plans for his successors were thwarted by the Holocaust.

Currently yeshivas operate in places of larger orthodox population, mainly in the United States and Israel. In 2005, Chabad Yeshiva in Warsaw began operating, and three years later, for the first time in Poland since the Second World War, 10 students received diplomas from yeshivas. In Warsaw also operates Lauder Morasha Scool which constitutes of kindergarten, primary school and secondary school which are not religious. However, the core curriculum has been extended by adding to it content associated with the history, culture and tradition of Polish Jews and the Hebrew language, which responds to the needs of the reviving Jewish community in Poland.