- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

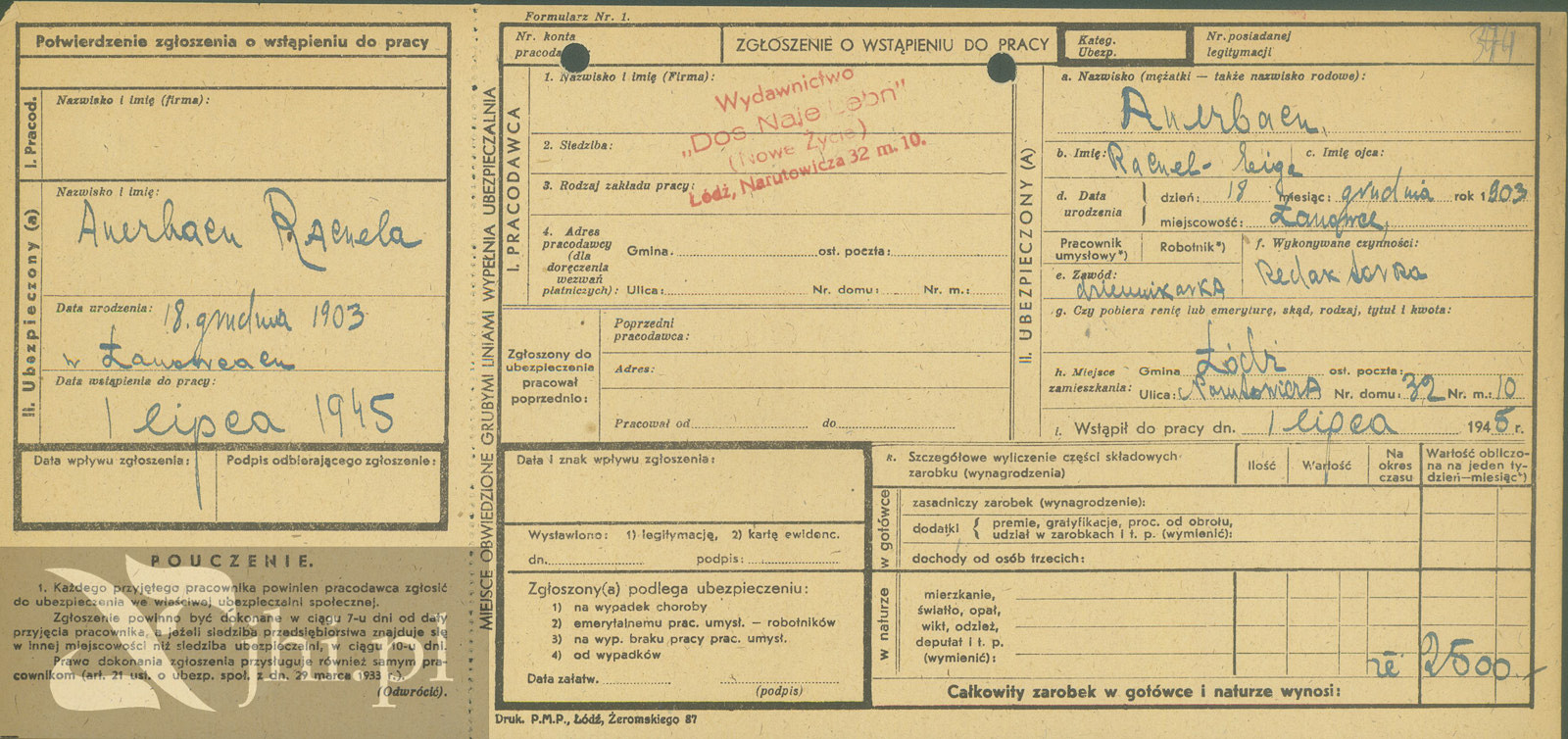

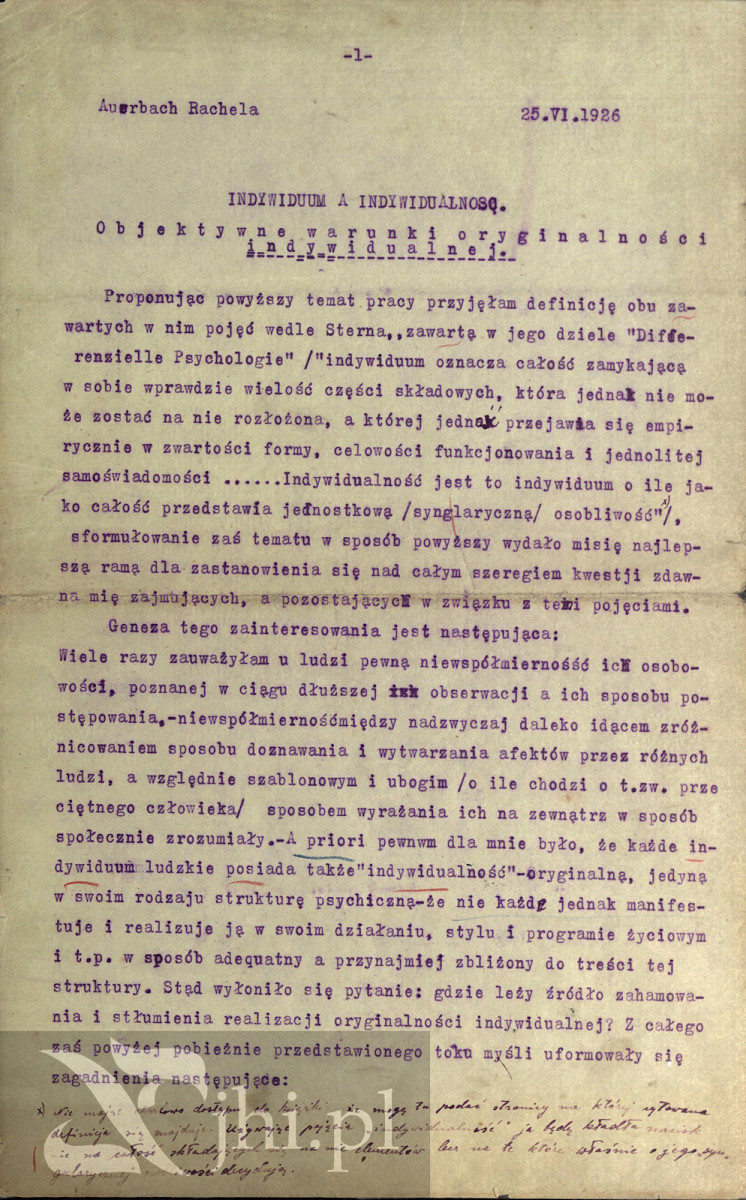

Among the documents from the second part of the Archive there are her pre-war academic and journalistic works, another part of Manger’s works, Auerbach’s letter to nephew Mundek in Lviv, and an escapee of the camp in Treblinka, Abram Krzepnicki’s testimony written by her. Auerbach was writing it down while working at 30 Franciszkańska Street at a sweets and artificial honey factory. The testimony is preceded with an introduction entitled What is Treblinka? — phenomenology of the enterprise of murder.

Many times, she strived at the Institute for regaining these documents or at least their copies. In her letter to Ber Marek, at the time Director of the JHI, from 20th March, 1951, she was trying to convince him that pre-war items could be returned to her in the form of originals (”they are of no archival value”, she argued), as far as the others are concerned, she asked for copies. She also informed that she was already working on the history of the Archive. Another letter, from April 1951, begins with the following words:

I am still awaiting photocopies of my manuscripts about Treblinka along with other articles, but unfortunately I still have not received them. I do not have to explain it to you how much do I desire to see these things and how much annoyed do I feel wondering why they have not yey arrived. Please, tell me why it is taking so long. I am also asking you to make sure that these things are sent to me as soon as possible.

The next letter, from 1967, was addressed to Tatiana Berenstein and Adam Rutkowski. It accompanied a letter of authorization given by Auerbach to, going to Poland, Miriam Peleg-Mariańska (Maria Hochberg), asking to give her the documents kept in the JHI’s Archive. Rutkowski hand-wrote on it: We have talked to Mrs Peleg (Mariańska) and explained that there was no way we could hand over the photocopies (microfilms). Today, it is still hard to establish for sure whether Auerbach received all these documents before her death in 1976. Well, certainly she had at her disposal (partly at least) photocopies of Krzepicki’s testimony.

Lack of access to these documents must have been for Auerbach an unusually harmful experience. She had a very emotional attitude to her writings and she was even physically connected with them. In the introduction to the work of Bechucot Warsz she emphasised that she worried about them like a mother about her children.

For her, they were testimonies to the murdered world and the world of the Holocaust, to which she attached huge importance. Though, she often said with bitter (auto)irony: Unfortunately, I was more lucky to save manuscripts than people...

….

When she emigrated to Israel, her main scope of activity was work on testimonies. When the Yad Vashem Institute was established in 1953, she became head of the Documentation Department (from March 1954). She also worked on theory of testimonies and methods of collecting them. For example, she thought that witnesses’ accounts should be recorded as writing disrupts the train of thoughts, destroys the suspense; besides, written record does not always reflect the language of the witness, they way of forming thoughts, work of their memory. However, at the time, not everyone perceived it in a similar way and it was hard for her to persuade the management of the Institute to find suitable witnesses for recordings. Out of 3000 testimonies collected by her till 1965, consisting of 82 thousand folios, only 600 of them are recordings.

At the end of the 50s, Auerbach, for some time, after an argument with the management of the Institute, was removed from her post, which she regarded as a mission. Later, after a longer dispute, which also took place in the press, her post was given back to her and as a result she came out of it stronger, energetically preparing for extending her Department and the scope of work to collect testimonies, which in her view were to be an evidence before the historical tribunal if they were not meant to be heard before the judicial tribunal. Only a few years later, in 1961, for the first time on such a large scale, the voice of the witnesses reverberated loudly in the courtroom.

The part that Auerbach played in preparations for the Eichmann trial is beyond overestimation. It was her and her co-workers who worked closely with the investigators and provided evidentiary material for the trial, made lists of witnesses, provided summaries and materials. At first, participation of about 20 witnesses was estimated. Auerbach was worried that the prosecution would concentrate only on official doecuments and direct evidence for Eichmann’s guilt. However, preparation works and closer relationship of the prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, with Auerbach herself and her Department resulted in the fact that the role given to the witnesses in this trial was changed completely and as a consequence the trial itself changed its character.

Auerbach herself was also preparing for giving testimony; she asked to assign 1.5h to her. She was given 45minutes and questioned even a quarter shorter. She was to speak before the ghetto fighters, talk about the situation before the uprising, above all, about the activity of Jewish artists in Warsaw, but finally she testified after Jicchak „Antek” Cukieman and Cywia Lubetkin. It was them who became key characters for Hausner and driving forces of the trial. Israel needed model heroes-soldiers. Auerbach’s quiet heroes, resisting in the ghetto mainly in spiritual way, receded into the background. This case hurt the writer, who was so nervous and irritated that she was not able to testify properly. In one of her letters, she wrote: I am deeply hurt and I will not recover either easily or quickly.

It did not stop her from working, which she continued until retiring in 1968. And also later, though not without troubles from the Institute. As always stubborn, fighting for what she regarded as most important, worried about the future of the department created by her. Only in 1974, after years of break, her own book was published „Warsaw Testaments: Encounters, Activities, Fates 1933–1943”. She neglected her own writing for years, devoting to the testimonies of others, feeling the burden of obligation, the burden of salvation. As she notes still during the war:

With every human who dies, dies a whole world. The consciousness of this fact has to become after this war a new motto of pacifism and new return to acknowledgement of an individual, postponed so much during present totalitarianism in favour of the abstract of collectiveness. With death of a Polish, German or Russian, dies a whole world, which exists in different variants. With death of every new survivor of the holocaust of the Polish Jewry, dies knowledge of him. Dies a species. Dies knowledge of their most important experiences, including the experience of the Holocaust.

She did not manage to finish the next book she was working on. It was published posthumously. A few years earlier, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She died in May 1976.

In the article, footnotes were omitted. More detailed information on the writer you will find in the article accompanying a compilation of Auerbach’s works entitled „Dziennik i inne pisma z getta” [Diary and other writings from the ghetto], which is to be published by JHI.