- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Gustaw Jarecka. Photo from the UW student ID card

Gustawa Jarecka was born on 23 August 1908 in Kalisz. Her father, Moszek Jarecki, was a merchant from Zagórów near Kalisz, and died in 1927, at the age of 57. Mother Natalia Jarecka came from Poznań.

Gustawa completed gymnasium in Łódź and studied Polish at the University of Warsaw (1925-1931). She was a writer, author of four novels: Inni ludzie (Other people, 1931), Stare grzechy (Old sins, 1934), Przed jutrem (Before tomorrow, 1936), Ludzie i sztandary (t. 1 Ojcowie, 1938; t. 2 Zwycięskie pokolenie, 1939) (People and banners, vol. 1, Fathers, 1938; vol. 2, The victorious generation, 1939) dedicated to working-class Łódź. Before the war, she was a left-wing writer concerned primarily with stories of poor and disadvantaged people. Her novels and fragments of books were published in ‘Głos Poranny’, ‘Dziennik Ludowy’, ‘Górnik’, ‘Myśl Socjalistyczna’ and ‘Nowa Kwadryga’.

She was also working as a teacher of Polish language and probably her profession was the reason why she found herself in the town of Wąbrzeźno in the mid-1930s. In late 1935 and early 1936, she described the town in her book for children, Szósty oddział jedzie w świat (The sixth troop goes out into the world).

Her good command of German helped her get the job of a telephone assistant and typist at the Jewish Council in the Warsaw Ghetto. It’s not certain how Jarecka, who didn’t take part in the pre-awr Jewish social life, found herself among Oneg Shabbat associates. For the Archive, she was copying documents passed through the secretariat of the Jewish Council, such as for example a transcript of the meeting on 22 July, during which Hermann Höfle dictated the German orders regarding the Great Deportation, statistics or an announcement about the deportation.

Marcel Reich-Ranicki, with whom she was working at the Judenrat, recalled her: I can see her in front of me, a chestnut-haired, blue-eyed, slim woman in the early 30s, calm and quiet. (…) She made a big impression on me from the start. Literature briught us together – neither German literature which she didn’t know much, nor Polish which I knew little about. We were talking about the French and the Russians, abour Flaubert, Proust, Tolstoy. I owe a lot to these conversations. [1]

![jarecka_2.jpg [9.31 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/57196a04df4bda1c6477570c72eecb55/jpg/jhi/preview/jarecka_2.jpg)

She was independently bringing up two sons – 12-year old Marek from her first brief marriage and 4-year old Karol.

To be a single mother in the ghetto must have been a great challenge (…) There was a struggle for everything. Even those who weren’t working were busy all day with finding food, clothing, exchanging things etc. The ghetto was selling out everything people had with every month, and people kept having less and less, but children kept growing up, they needed to be fed and dressed. From Reich-Ranicki we know that the boys had different fathers, which can be disapproved of even today. She must have been an independent, emancipated woman – she didn’t have a husband chosen by an orthodox family, she led her own life. [2]

From Marcel Reich-Ranicki’s account we know that she was a very brave woman: I was finding solace in her which my own mother couldn’t offer me anymore. Sometimes it seems to me as if Gustawa loved me. Despite this, when Ranicki was reading aloud the order from 22 July for transcription and reached the sentence saying that wives of Judenrat’s employees won’t be deported, Gustawa stopped writing down the Polish text and said, without lifting her head from the typewriter: You have to marry Tosia today. [3] In fact, he married her the same day.

Thanks to her work at the Judenrat, Jarecka avoided the first deportation in the Summer of 1942. Ringelblum asked her to describe what she saw. She is assumed to have written The last stage of resettlement is death, a harrowing reportage about deportations from the ghetto, written in September 1942.

![jarecka_3.jpg [181.90 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/1c765b21692d57ab1e4b7409d9d049d7/jpg/jhi/preview/jarecka_3.jpg)

The document presents the first two days of the operation along with preceding events – the night of violence on 17/18 April, when the Germans killed 53 people in the ghetto, increasing terror, fear and uncertainty.

On 22 July 1942, several cars and two lorries arrived in front of the Jewish Community building, called then pompously The Main Edifice of the Jewish Council. The pretentiousness of the name could be justified with the fact that, after all, it was the biggest community of Jews in Europe at that time. The arrival of several cars brought an end to this greatness. [4] The account is full of despair, but also hope that it will shake the conscience of the world and show at the perpetrator who will be put to a trial. [5] She wrote: these notes are driven by an instinct, a desire to leave a mark, by despair close to crying sometimes, and from a will to justify one’s life, remaining in deadly uncertainty. We have nooses on our necks, and when they loosen a little, we shout out. [6] The document juxtaposes the language of emotion with the language of dry facts, strongly rhetorical and metaphorical introduction is connected with the language of the German official documents, the perspective of a persecuted victim – with a detached language of the executioner. [7] We note a proof of guilt which is useless for ourselves. The trace should be thrown like a stone under the wheel of history, in order to stop it. The stone has the weight of our experience which had reached the bottom of human cruelty. It contains the memory of mothers mad with grief after losing their children; a memory of the cry of children who were carried to the road to death without coats, in their summer clothes, barefoot, and walked crying, unaware of the horror which was happening to them; a memory of despair of old mothers and fathers who had to be abandoned by their adult children; and the stone silence in a dead city, once a sentence on three hundred thousand people was implemented. [8] (translated by Olga Drenda)

The document, written on four typewriters, ends mid-sentence. Probably she didn’t have enough time, or the effort of describing the Holocaust day by day was too exhausting.

One of the last accounts of Jarecka was shared by Hilel Seidman, who spoke to her in December 1942. Jarecka said she was sorry that she doesn’t know Yiddish or Hebrew. She told Seidman that if she survives the war, she will learn these languages and write in them. [9]

Gustawa Jarecka spoke Polish, had „a good appearance” and Polish friends who offered her help in escape, but she turned down these offers, not wanting to leave her sons.

On 18 January, Ranicki found himself in a column of people led to the Umschlagplatz. Jarecka and her children were there as well. I made a sign to Gustawa Jarecka, who stood in our line with two of her children, that we want to run away and that she should join us. She nodded. I was about to run, but I stopped for a second, afraid of being shot. Tosia pulled me away from the line and we ran towards the gate of the house of the dear Miła street, destroyed in September 1939. Gustawa Jarecka didn’t run with us, she died with her two children in a train to Treblinka. [10] (translated by Olga Drenda)

From Stanisław Adler’s account we know that Gustawa Jarecka died with her children in the train to Treblinka, probably due to lack of access to air.

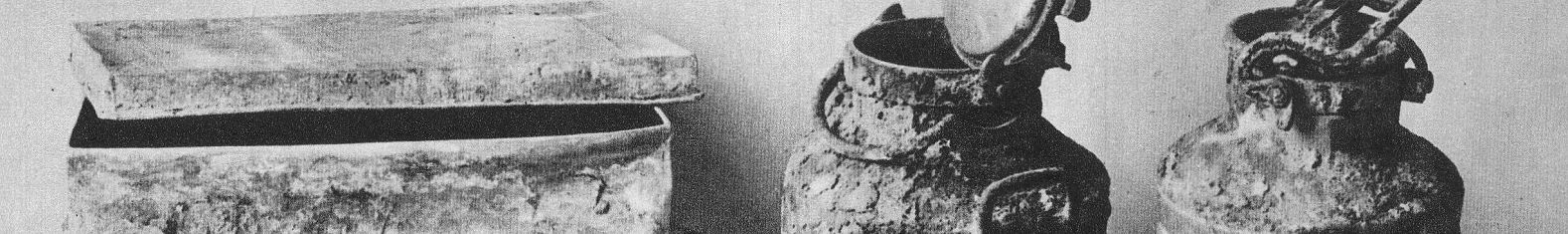

![jarecka_4.jpg [142.65 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/3ac4ca7f35733d6e4e2bf29207567bf0/jpg/jhi/preview/jarecka_4.jpg)

Gustawa Jarecka’s account can be found in volume 33 of the complete edition of the Ringelblum Archive (only in Polish: Getto warszawskie, cz. I).

In 2017, it was also published separately by the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute.

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

Footnotes:

[1] Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Moje życie, przeł. Jan Koprowski, Michał Misiorny, Wyd. Muza SA, Warszawa 2000, s. 152.

[2] Anna Duńczyk-Szulc in: Anna Sańczuk, http://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,127763,23071460,archiwum-ringelbluma-gela-gustawa-rachela-cecylia-zydowki-z.html

[3] Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Moje życie, op. cit., s. 153.

[4] Gustawa Jarecka, The last stage of resettlement is death, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017, p. 17.

[5] Marta Janczewska, Introduction [in:] Gustawa Jarecka, The last stage of resettlement is death, op. cit.

[6] Gustawa Jarecka, The last stage of resettlement is death, op. cit., p. 11.

[7] Marta Janczewska, Introduction [in:] Gustawa Jarecka, The last stage of resettlement is death, op. cit.

[8] Gustawa Jarecka, The last stage of resettlement is death, op. cit., p.12.

[9] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017, p. 323.

[10] Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Moje życie, op. cit., s. 170.

Bibliography:

Gustawa Jarecka, The last stage of resettlement is death, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, t. 33, Getto warszawskie, cz. I, red. Tadeusz Epsztein, Katarzyna Person, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2016.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017.

Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Moje życie, przeł. Jan Koprowski, Michał Misiorny, Wyd. Muza SA, Warszawa 2000.

Anna Sańczuk, http://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,127763,23071460,archiwum-ringelbluma-gela-gustawa-rachela-cecylia-zydowki-z.html

Stanisław Adler, Żadna blaga, żadne kłamstwo… Wspomnienia z warszawskiego getta, Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów, Warszawa 2018.