- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

The Torah is what non-Jews may understand as the Old Testament. In Judaism, the word ‘Torah’ can be used to mean three things. Firstly, the Torah includes the first five books of the Hebrew Bible – the Five Books of Moses – known in Judaism as the Written Torah. When used for purposes of worship, it takes the form of a Torah scroll, which is read in synagogues on Mondays, Thursdays, Shabbat, Rosh Chodesh (the first day of the new month in the Jewish calendar), festivals and fast days. The word ‘Torah’ can also be used as a synonym for the Tanakh, which is comprised of all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible. Lastly, in Judaism the Torah can mean the totality of Jewish teaching, culture and laws of practise. This represents what was not recorded in the Five Books of Moses, and is known as the Oral Torah.

The Oral Torah and the Talmud

The development of the Talmud progressed rapidly as the number of sages increased greatly after the triumph of Simon ben Shetach over the Sadducees (early 1st Century BCE), when he finally cleared the Sanhedrin (the Great Assembly of elders, which had judicial and legislative powers) of them, leaving only Pharisees[2]. It was a monumental time in the history of Judaism, however, the teachings still were not written down.

The Oral Torah was memorised and passed down orally in an unbroken chain from each generation until its contents were finally authorised to be put in writing after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The Jewish population faced significant existential threat, and it was then that, due to the dispersion of the Jewish people, the Oral Torah came into existence in written form, first as scrolls, and eventually in book form[1]. This process took place between the 2nd and 6th centuries.

Those who practice Orthodox Judaism believe that at least part of the Oral Torah was given orally from God to Moses at the same time as the prophet received the Written Torah on Mount Sinai during the Exodus from Egypt. This fact is recognised as one of the Thirteen Principles of Faith by Maimonides (1138-1204), one of the greatest medieval Jewish scholars. The Oral Torah is composed largely of the Mishnah, compiled between 200-220 CE by Rabbi Yehudah haNasi, and the Gemara, which is a collection of commentaries and debates concerning the Mishnah, which together form the Talmud.

The Talmud is written in Hebrew and Aramaic, and exists in two versions: the vastly studied Babylonian Talmud, compiled by scholars in Mesopotamia (Babylonia) around 500 CE, as well as the Jerusalem Talmud, compiled earlier, around 400 CE, but much shorter, incomplete and in consequence, for centuries studied less frequently. Usually, ‘the Talmud’ refers to the Babylonian Talmud.

The entire Talmud consists of 63 tractates with commentaries and notes on each page, called Tosafot (Hebrew, ‘additions’), indicating that the commentary was an addition to that of Rashi, Rabbenu Hananel, Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz, and Rabbenu Gershom. (Rabbenu was the title of the most respected rabbis, or religious scholars). The structure of the Talmud follows that of the Mishnah. The Six Orders (major divisions) of the Mishnah are divided into tractates of more specific topics. It’s worth to note, that neither version of the Talmud, the Jerusalem nor the Babylonian Talmud, covers the entire Mishnah. For example, in both versions of the Talmud, only one tractate of ritual purity laws is explored, that of Niddah (Family Purity Laws).

![stein_nad_książką_zw.jpg [498.79 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/1/24/b881079a0cff2f4965e5b6c03418b4e2/jpg/jhi/preview/stein_nad_książką_zw.jpg)

A tour of the Talmud

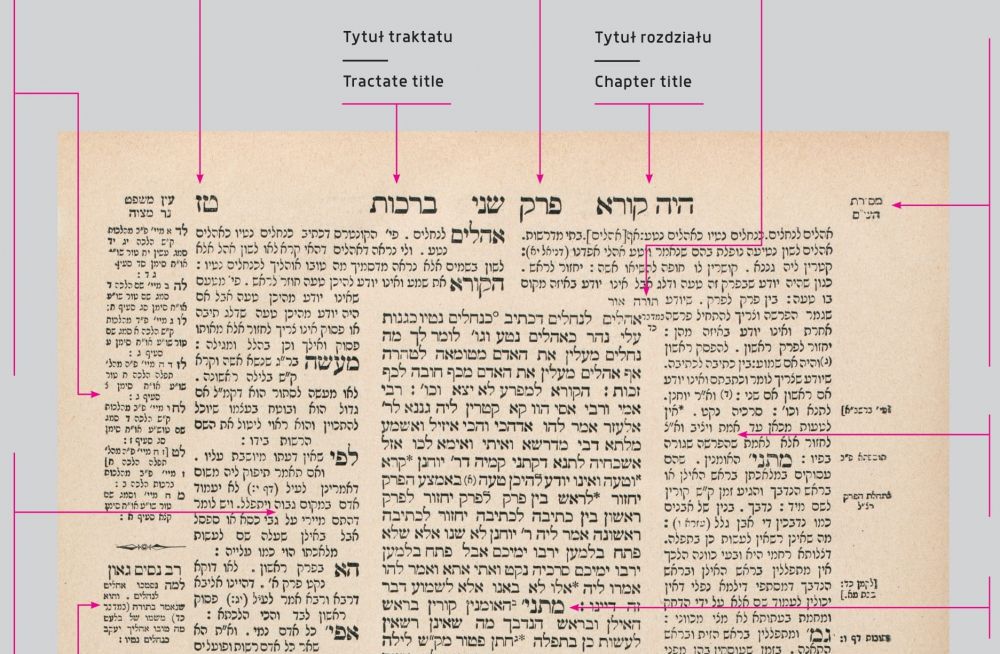

The Talmud is divided into eight main parts. On each page, the main body consists of the Mishnah (Hebrew, ‘repetition’) and the Gemara (Aramaic, ‘study’). The Gemara appears below the Mishnah as an analysis and elaboration of the material from the Mishnah above. Tosafot are collected medieval commentaries arranged according to the Talmud tractates, mainly written in France, Spain and Germany between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Rashi commentary is located to the right of Tosafot. Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki) compiled the first complete commentary on the Talmud. Next to Rashi commentary is Mesoret Hashas (Hebrew, ‘Transmission of the Six Orders’), which is an index compiled by Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz in the 16th century and supplemented by successive scholars. What’s more by Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz – the Torah Or is what gives the sources of biblical verses quoted in the Talmud, Ein Mishpat giving references to Talmudic laws that can be found in early halachic codes: Mishnah Torah, Sefer Mitzvot Gadol, and Arba’ah Turim (Tur), as well as Ner mitzvah, enumerating the laws cited in Ein Mishpat. Found on each page are glosses, or textual emendations, by Akiva Eger (1761-1837), the Vilna Gaon (1720-1797), Joel Sirkes (1561-1640), and Nissim ben Yaakov (990-1062).

Page number, tractate name, chapter number, and chapter name are likewise printed on each page. They are located at the top of a page.[3]

![talmud_gaon_2_fb.jpg [888.39 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/1/24/8f95a576b1dcef4f992a0e8b50f286e6/jpg/jhi/preview/talmud_gaon_2_fb.jpg)

What do Jews learn from the Talmud?

The Talmud is still vastly studied today, in yeshivot, in the synagogue during kollel (advanced study of the Talmud and rabbinic literature) or in between prayers, and at home. The Talmud covers all subject matters integral to Jewish life, such as Shabbat, the Laws of Niddah, the Laws of Yom Tov (festivals of biblical origin), blessings, fasts, and many more.

Jews today can find a lot of meaning as well as practical knowledge from the Talmud and commentary. For instance, one could ask, on Shabbat before the meal, should only one male recite Kiddush (sanctification over wine) for everyone, or should each adult male recite it for himself and family. From the Talmud, we can derive the answer, as it states: “If people were sitting in the Beit ha-Midrash [study hall] and light was brought in [at the termination of the Sabbath], Beit Shammai [a school of scholars] say that each should recite the blessing for himself, while Beit Hillel [another school] say that one person should recite the blessing on behalf of everyone” (Proverbs 14-28, Berachot 53a)[4]. Based upon this, the Vilna Gaon “derives a general precept that when a number of people are to perform a mitzvah [commandment/good deed done from religious duty], it is preferable for one person to recite the blessing for everyone, rather than for each person to recite it separately” (Glosses, Ha-Gra, Orach Chayyim 8:12). In this way the Talmud and the commentaries from, amongst others, the Vilna Gaon can guide the Jewish people in even basic halakha (Jewish law).[5]

The Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman, or Ha-Gra, is known to have been one of the greatest Talmudic minds. He spent all his time studying, even as a child, and at age 7, gave his first lecture on the Talmud. Despite being so well esteemed, appreciated, and knowledgeable, he didn’t actually publish any of his works during his lifetime. He is known to have known several tractates by heart; this is a rather common phenomenon, as Jews tend to re-learn tractates of the Talmud many times, often resulting in knowing parts of the Talmud from memory.

A lot of the Talmud is written as a conversation. A statement will be made, after which questions will be asked, answers will be put forward and more answers will be suggested, frequently going on for pages. It becomes evident that there have been hundreds of years of analysis and knowledge packed into one place. This often proves to be an excellent way to learn, as questions arise constantly in daily life; learning from the discussions led by such eminent scholars proves to be a very efficient way to learn.[6]

![gaon_portret_zw_1a.jpg [494.93 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/1/24/fc2652113d0abba2eb7342d323dfe1c2/jpg/jhi/preview/gaon_portret_zw_1a.jpg)

Why is the Talmud still studied?

Over the many centuries the Talmud has existed, Jews have studied it for a variety of reasons, namely practical reasons. As mentioned, the Talmud contains halakha – this is incredibly important for Jews to live according to the Torah, the Word of God. To quote Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, who devoted almost half a century to translating the Talmud, “[The Talmud is] a central pillar for understanding anything about Judaism”[7]. This clearly shows, in a single sentence, just how important the Talmud actually is; it isn’t ‘just another religious book’, but a way of life. It is the link between the Torah and Jewish practise and beliefs.

The Talmud is also a way to see and comprehend discussion between thousands of rabbis spanning centuries before the work was compiled and put onto paper. It is best to study in Hebrew and Aramaic, but translations are available, meaning not only those who know these languages can learn from the Talmud. The Talmud is written largely in Aramaic due to the fact that at the time, that was the ‘language of the masses’ and could be understood by everyone. Hebrew, the “holy tongue”, was used to discuss strictly holy matters.

Both Hebrew and Jewish Aramaic are written in the standard Hebrew alphabet, however, in the standard edition of the Talmud, there are two kinds of lettering. The main text is in block lettering, but many of the commentaries are written in a font known as Rashi script, which is a rounded font, that can also be found in the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law), which likewise contains glosses by the Vilna Gaon[8].

Yeshiva students spend hours a day analysing the Talmud – it is a massive source of knowledge that can be used to not only study, but to come up with one’s own questions and answers, too. This is especially useful when students are going into adulthood, properly commencing avid Torah study. It is a way to not only gain knowledge, but to deepen one’s spiritual life.

The Talmud and the study of it is one of the central aspects of Judaism. For generations, the Talmud has been studied boundlessly, from its original commentaries until today, with the hope that future generations will do the same. As a bridge between the Word of God and Jewish observance, it is the basis of everyday life for so many Jews, something to be cherished, yet taken seriously. The study of the Talmud is one of the greatest tools to ensure preservation of the Jewish religion as it was thousands of years ago.

Footnotes:

[1] Benjamin D. Sommer, Jewish Concepts of Scripture – A Comparative Introduction, NYU Press, New York, 2012, pp. 31-32.

[2] Michael L. Rodkinson, The History of the Talmud, Volume I, 1903, p. 7.

[3] Talmud Bavli, Artscroll Mesorah Publications, 2004.

[4] Rabbi J. Simcha Cohen, Shabbat The Right Way – Resolving Halachic Dilemmas, Urim Publications, 2009, p. 19.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Menachem Posner, “21 Talmud Facts Every Jew Should Know”, Chabad.org. Retrieved 13th December 2021.

[7] Raphael Ahren, 9th August 2012, “Never mind the Bible, it’s the sanity of the Talmud you need to understand the world and yourself” The Times of Israel. Retrieved 8th December 2021.

[8] Menachem Posner, “14 Facts About the Code of Jewish Law (Shulchan Aruch), Chabad.org. Retrieved 14th December 2021.