- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

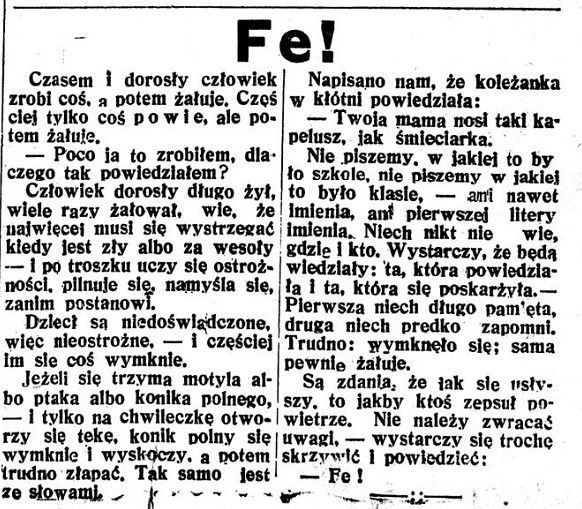

On 9 October 1926, a reporter of „Mały Przegląd” visited the Krasiński Garden in Warsaw in order to find out about the playground fenced off with barbed wire, about which the editorial staff was informed before. On 22 October, the young journalist wrote: There is grass around the playground. The entire playground is fenced off with barbed wire. Loosened spaces indicate that despite sharp barbs, children do get in. Probably when a ball falls onto the grass (…) The problem of bringing back the ball when it falls onto the grass, hasn’t been regulated until present day. But a ball will fall onto the grass every now and then, even during a most cautious play. The fences around playgrounds in this garden, as well as in other ones, made it impossible for children to play freely and forced them to cheat, which especially worried the young reporter. A child looks around if there’s no guard around, and quickly jumps in to bring his property back. The young reporter notices that children learn how to omit the bans and how to run away from the guard who could even punish them with his stick. They’re deprived of real joy of playing outdoors. He ends his article with a conclusion: Children get used to ignoring regulations and avoiding guards, they learn to be afraid and not to listen.

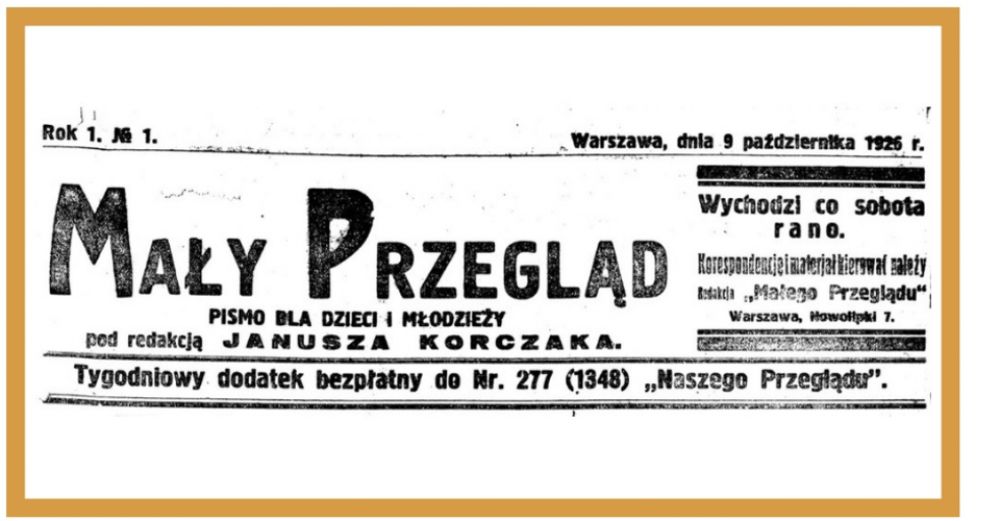

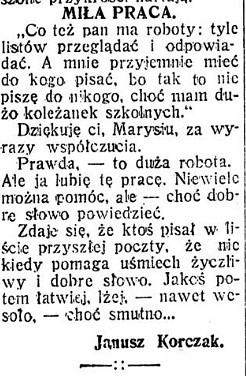

This is only one of hundred of thousands of articles, notes, interviews, news and letters which appeared on the pages of „Mały Przegląd” — the only periodical whose contributors were children. „Mały Przegląd”, as a weekly extra to „Nasz Przegląd” („Our Review”), was published from 9 October 1926 to 1 September 1939. The founder and the first editor of this extraordinary magazine was Janusz Korczak. The editorial office was located in two rooms made available by „Nasz Przegląd” at Nowolipki 7. Whoever wants to, may have a say, whoever wants to, may come and write something here, at the office. (…) Those who are embarrassed about ugly handwriting or grammar mistakes, will be told by the editor, that it doesn’t matter. The proofreaders will fix it. (…) News may be delivered personally, by phone, by letters, dictated or written. It should all be comfortable, not make anyone embarrassed, and without laughing at anybody (To my future readers, „Nasz Przegląd”, 3 October 1926).

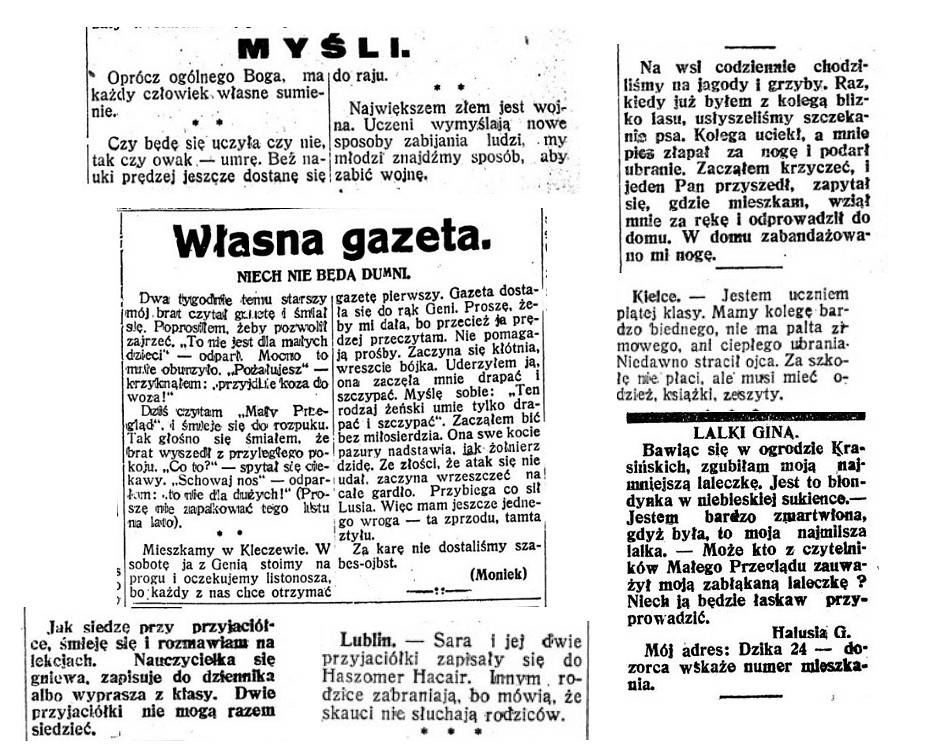

The first secretaries of the magazine were: Madzia Markuze, Edwin Markuze and Emanuel Sztokman, while Chaskiel Bajn was responsible for selecting letters from children. Initially, letters were arriving from Warsaw, later – from faraway cities and towns, and eventually even from abroad. They were written by children from various backgrounds – intelligentsia, business families, factory workers and factory owners, Polonised and Orthodox Jewish, rich and poor. The magazine rarely contained literature (poetry, fairytales, short stories), because according to Janusz Korczak’s original idea, the magazine was intended to contain authentic accounts – documents, information, reportage. In their letters, children were sharing personal issues, their daily joys and concerns, events at school, at home, on holiday. They were describing their play with other kids, playground games, the books they read, what they saw in the cinema and in the theatre. But the letters included also accounts of personal tragedies, illnesses, poverty, unemployment.

Korczak divided the periodical into sections: „Current news” — with letters from Warsaw, and „Domestic news” — for letters from outside the capital. In case someone was concerned about lack of response, Korczak would answer: To everyone who sends a letter to „Mały Przegląd” — please don’t worry that it doesn’t appear immediately, it wasn’t lost. Here’s how it works: through the whole week, we’re collecting letters. Then Chaskiel is numbering them, writing down the name and address in a book. (…) Letters are tied together with a green ribbon, and placed in a case. The letters are being numbered with a blue pencil. Then I’m reading the letters in my glasses, and with my red pencil, I’m leaving a mark – what to do with each letter. (…) We must not rush, because there will be a mess, and people will say that „Mały Przegląd” is silly. (…) Especially important, difficult letters wait longer, because we must ask various people what to say, or we must find out if everything was true. In a paper, everything has to be done carefully and with attention. Everything must make sense. (To those who are concerned or wondering, „Mały Przegląd”, 5 November 1926).