- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Monday, 3 August, 4 PM

August 1, 2019

On 3 August 1942 two students of the Ber Borochovv school at 68 Nowolipki street – Dawid Graber and Nachum Grzywacz, along with their teacher Izrael Lichtensztajn, hid the last section of the first part of the Ringelblum Archive. Ten boxes with documents, as well as their own testaments and accounts, were buried in the basement of the school.

NACHUM GRZYWACZ

He was 17 in August 1942. He was born in Warsaw, received traditional religious upbringing, and began his education at the 68 Nowolipki school named after Ber Borochov – an ideologist of the Poalej Syjon party, which some of the Archive contributors were associated with. Before Grzywacz had to give up his education (having been born to a poor family, he had to take up work), he met Izrael Lichtensztajn, the school principal. This meeting helped shape his opinions, and the 68 Nowolipki street became an address important for him for the rest of his life.

When the war broke out, Grzywacz was working in a public kitchen for children, functioning in the building of his former school. The school was officially closed, but Izrael Lichtensztajn – principal before the war, now a member of Oneg Shabbat – was organizing secret classes there. He encouraged Nachum and his friend Dawid Graber to join the work on the Archive. For confidentiality purposes, the boys knew only Lichtensztajn and Hersz Wasser, secretary of the Archive. They were assisting with works on the Archive, putting documents in order and packing them.

Nachum Grzywacz added his testament and diary to the last of ten boxes. He died soon afterwards, during the Great Deportation, in the Summer of 1942.

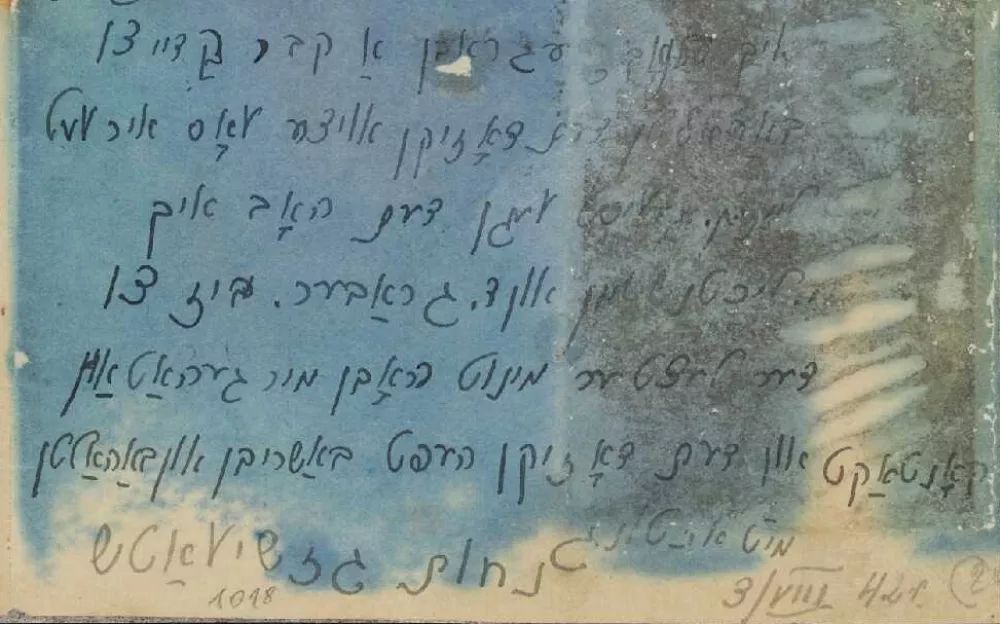

Fragment of Nachum Grzywacz's testament

30 July 1942

While I’m writing this letter, I’m at work, it’s 30 July 1942, 6 PM. I’m fully clothed and I have some food with me. I see them running, so I walk downstairs to the street and I find out that Smocza street from Dzielna to Gęsia have been blocked by the gendarmerie. My parents live at 41 Pawia street. I’m quickly asking what’s happening and I learn that the street is blocked. I don’t know what is happening to my parents. I’m waiting for the right moment to run and find out how they are. Now I hear shouts. They’re coming. I’m in the yard. There was only fear.

I’m now in the building and I’m going to my parents to see how they are. I don’t know my fate. I don’t know whether I will be able to tell you what happened later. Remember: my name is Nachum Grzywacz.

3 August 1942

I’m writing my testament in the time I have described here. I’m sat here waiting. We have lost contact with all our friends. Everyone is on their own because chaos reigns in the Jewish ghetto. The tree was cut down, years of work lost. Me, comrade Lichtensztajn and Graber have decided to describe the events. Yesterday, we stayed up late, because we didn’t know if we will still be alive today, on 3 August 1942. Ten minutes after half past one, I’m finishing my writing. We want to stay alive not for personal reasons, but to alert the world.

(translated by Olga Drenda)

DAWID GRABER

Dawid Graber was born in 1923. He was learning in cheder – a religious school for children, and later in the Zionist Borochov school. Graber was also involved in Zionist youth organizations.

During the war, he found employment in the public kitchen located in his former school. Soon its principal, Izrael Lichtensztajn – an Oneg Shabbat associate – invited him to join the group. Working for the Archive became Dawid Graber’s meaning of life. When he was writing his testament, he was 19. He died probably during the Great Deportation in the Summer of 1942.

Dawid Graber, My testament

3 VIII 1942

I’m writing my testament during the deportation of the Jews of Warsaw. It has been taking place since 20 July, constantly. Now, when I’m writing down these words, one cannot even go outside. Nobody can feel safe even at home. It is already 14th day of this horrible procedure. We have nearly lost contact with our comrades. Everyone is on their own. Everyone is trying to save themselves. There is three of us left: comrade Lichtensztajn, Grzywacz and me. We have decided to write our testaments, collect some evidence from the deportation, and bury it. We have to rush, because there is no certainty… Yesterday, we have been working until late.

What we were unable to shout out to the world, we have buried in the ground.

Monday, 3 August, 4 PM

One of the streets next to us has already been blocked. The moods are terrible. We’re expecting the worst. We will probably be burying the last part soon. Comrade Lichtensztajn is concerned, Grzywacz is a bit afraid. I am oblivious. I feel subconsciously that I will free myself of all my worries.

Goodbye. I hope we can bury it… Even in such a time, we haven’t forgotten anything… We have been at work until the very last moment.

(translated by Olga Drenda)

IZRAEL LICHTENSZTAJN

Izrael Lichtensztajn was born in 1904 in Radzyń Podlaski, to a merchant family. After completing his studies at the Jewish School for Teachers in Vilnius, he became a teacher at a gymnasium and strongly dedicated himself to social activism. He was active in Jewish cultural and sports organizations, promoting physical culture among the working class. He was an ardent Zionist, and a member of Poalej Syjon-Lewica. Throughout the interwar period, he was also writing, working as an editorial assistant at the „Literarisze Bleter” literature magazine, collaborating with leading Jewish daily newspapers and publishing children’s stories in the press.

In 1932, he moved from Vilnius to Warsaw, where he became the principal of the Ber Borochov school. In 1939, he married Gela Seksztajn, painter and illustrator. When the war broke out, he joined the Jewish social help movement. As a member of the CENTOS (Association of Children and Orphan Aid Organizations), he was organizing official and secret education, which was documented by him for the purposes of the Ringelblum Archive after the closing of the ghetto. He remained active as a teacher, working also as a manager of the school and children’s public kitchen at 68 Nowolipki street.

It was the building where the first part of the documents from the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto was buried – including Lichtensztajn’s testament. After the Great Deportation, Lichtensztajn joined preparations for military resistance. He died together with his wife and daughter in the first days of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, in April 1943.

Izrael Lichtensztajn, My testament

31 July 1942

With great enthusiasm, I have engaged myself in gathering the archives. I was named the guardian of the documents. (…) The material is well hidden. I hope it will survive – it will be the most beautiful, the best outcome of what we did in these cruel times (…)

I don’t want thanks, monuments, anthems, I only want my brothers and sisters in Eretz Israel to know where my remains were. I want my wife Gela Seksztajn, a talented painter, to be remembered (…) I want my daughter to be remembered (…) She is worth sparing a memory too.

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

Testaments of Nachum Grzywacz and Dawid Graber were published in the 23th volume of the complete edition of the Ringelblum Archive – Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego (only in Polish), and the testament of Izrael Lichtensztajn in the 5th volume of the Archive – Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn (in Polish).

Original fragments of the testaments can be seen at the permanent exhibition at the Jewish Historical Institute – What we have been unable to shout out to the world.