- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

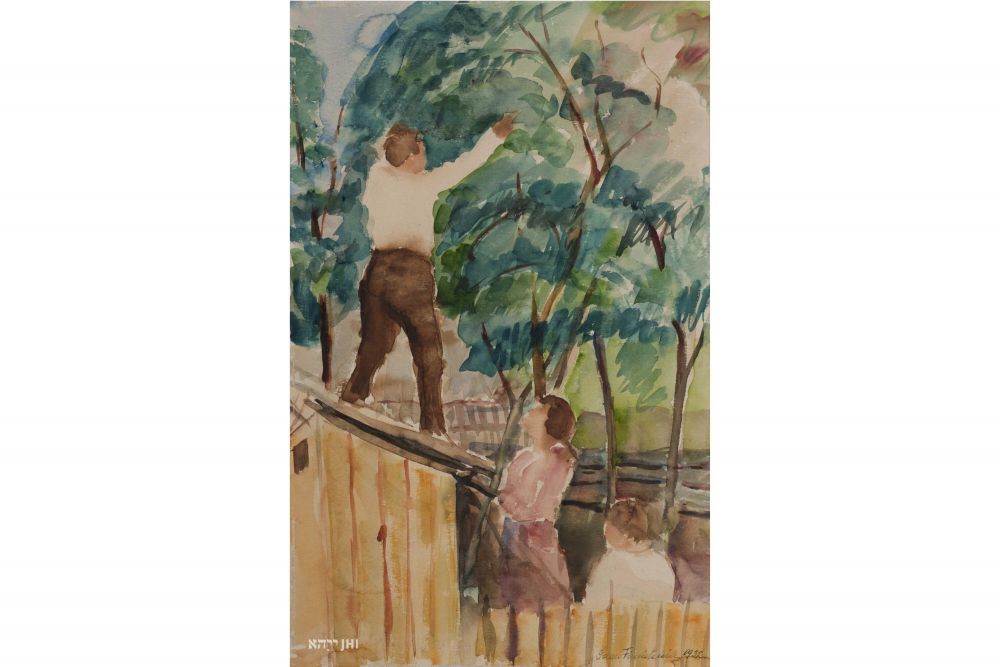

Samuel Finkelstein, "Picking fruit", 1932, JHI collection

Whilst a ‘New Year for Trees’ may seem like a slightly strange concept, it is an important time for both spiritual and practical reasons. Many people are familiar with Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Although Tu BiShvat is a Rosh Hashanah for trees, it is still very significant for humans – there is a popular quote from the book of Deuteronomy, which has many interpretations by scholars including Rashi and Maimonides. It reads, “Is the tree of the field a man?” (Deuteronomy 20:19).

This line has been interpreted in myriad ways, including directly comparing man to the tree of the field[1]. We know that even during the winter, trees may look idle, yet beneath the surface, their roots are growing and becoming stronger. Therefore, us as humans, by having strong roots and faith, we can be fruitful and continue to dedicate ourselves to God. This is a strong concept for many Jews during Tu BiShvat.

Why does it fall on 15 Shevat?

It was of great importance to determine when the new year for produce started, due to the seven-year agricultural cycle that is in accordance to Torah law. Each year within this seven-year cycle was important – when the Holy Temple stood in Jerusalem, on years one, two, four and five of this cycle, it was required of farmers to separate, one tenth of their produce (tithe) and eat it in Jerusalem, with another tithe to be given to Kohanim and Leviim (priests and musicians in the Temple. Today, both Kohanim and Leviim are known as descendants from the tribe of Levi, but Kohanim are also descendants of Aaron). On the third and sixth years, owners gave their tithe to the poor.

The seventh year is special in that, during the year, no agricultural work should be done. The laws of the seventh year apply specifically to plants which need their seeds to be sown, and the soil they’ll be planted in to be tilled[2]. This is known as the Shmita year.

It was established by Rabbis that a fruit which blossomed before 15 Shevat is produce from the previous (Jewish) year. If after, it was produce of the new year (for trees). This date was chosen as, in Israel (as well as surrounding Mediterranean countries), rain starts to fall around the time of Sukkot – 15 Tishrei, 15 days after Rosh Hashanah, the start of the main Jewish New Year. It is said to take around 4 months, until 15 Shevat, for the rain of the new year to soak through soil and trees, and therefore produce fruit. Hence, the 15th day of Shevat is considered the new year for trees and fruit production. Tu BiShvat is mentioned in the Talmud, in tractate Rosh Hashanah.

Shmita

According to Torah law, there is a seven-year agricultural cycle; the seventh year is known as the Sabbatical year, a Shabbat of the Land, which is a year of rest from farming, no tithes are separated, and all products that grow during this year are considered ownerless – anyone can take from it. This seventh year is known biblically as the Shmita year.

This year, 5782, is in fact a Shmita year. The laws of shmita do not apply to the Diaspora, they are only applicable in Israel. These laws do not only apply to big agricultural plots and fields – privately grown produce in gardens, greenhouses, and the like are too subject to these laws. The laws of shmita were first mentioned in the Book of Exodus, after which it is further mentioned multiple times. Shmita literally means ‘release’ – this period can be seen as a time of releasing what we have known up until the seventh year; often, before Shabbat, the seventh day of the week, there is a big rush to cook, clean, prepare, and let go of the work week that preceded. It is a time of releasing the energy and stress felt before the Shabbat candles were lit. As Shmita can be looked at as a year-long Shabbat for the Land, the word ‘release’ seems all the more fitting, and a lot of preparation is often needed before the Shmita year commences.

Although shmita laws generally apply to Israel and not the rest of the world, there are still a few things that are applicable to those who live in the Diaspora. For example, during Shmita, it is not advised to buy or receive produce that was grown in Israel – the fruits are considered holy, thus one may also not sell such fruits as they may not be wasted or destroyed in any way.

Applying to anywhere in the world, it is a positive commandment to nullify a loan in the Sabbatical year, as it states in Deuteronomy 15:2, “All of those who bear debt must release their hold”[3]. This interpersonal loan amnesty is known as a pruzbol. Although this concept is mentioned in the Torah, now it is a Rabbinic commandment, as the Torah notion applies only when most of the Jewish nation live in the Land of Israel, meaning, when the Jewish nation is not in exile (which has been the case since the destruction of the Second Temple). This is yet another example of how Shmita is, and symbolises, releasing.

Tu BiShvat traditions today

It is a widespread custom to eat fruits on Tu BiShvat, especially the fruits of the Holy Land, the Land of Israel, which are dates, figs, grapes, olives, and pomegranates. It is also common to eat a fruit that one hasn’t already consumed this season, in order to be able to say the Shehecheyanu blessing, which is a blessing thanking God for sustaining and enabling us to reach this moment. According to religious tradition, Tu BiShvat isn’t a day for planting new trees; the “new year for planting” is in fact on 1 Tishrei, just as Rosh Hashanah. Today it has, however, for some people, become a custom (especially in Israel) to plant new trees on this day.

A lot of Jews have the custom of eating 15 different fruits on Tu BiShvat, to commemorate the fact that this holiday falls on 15 Shevat. Ashkenazi Jews also recite psalms. Sephardi Jews accompany their “feast of fruits” with songs called complas. Families tend to sit all together and enjoy all of these fruits with other foods, and with wine or other beverages, known as Seder Tu BiShvat. As it is a minor holiday, and is a joyous occasion, it is forbidden to fast during this time[4].

Overall, it is a time to thank God and focus on what He has provided us with to sustain us and enable us to live our lives the way we do.

Footnotes:

[1] A Closer Examination of Deuteronomy 20:19-20, Akiva Wolff, p. 147, jewishbible.org, retrieved 4.01.2022.

[2] The Hazon Shmita Sourcebook, Yigal Deutscher, Anna Hanau, Nigel Savage, Shmita Project, First Edition, August 2013, p. 31.

[3] Ibid. p. 42

[4] Tu bi-Shevat, The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, britannica.com, retrieved 17.01.2022.