- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

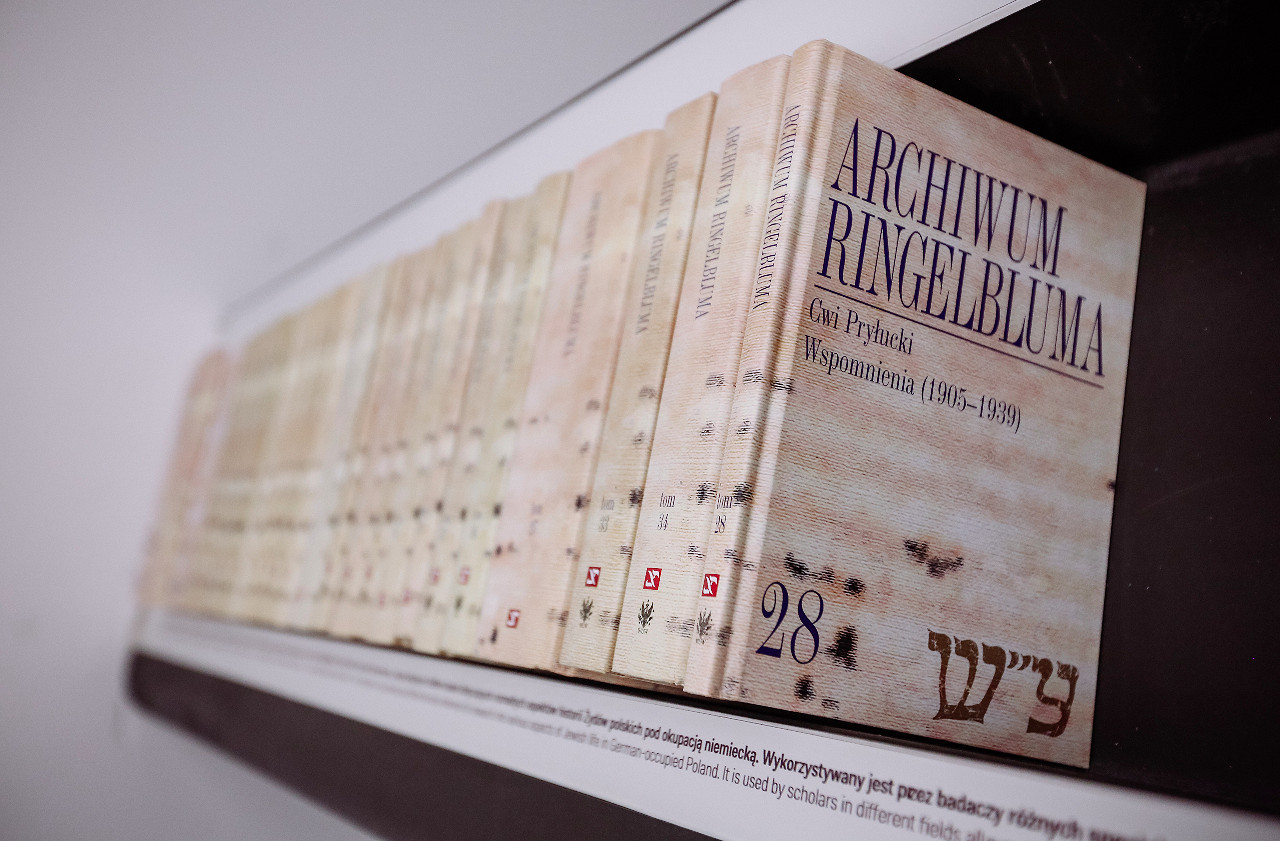

It has to be emphasised that translating the entire Ringelblum Archive from Yiddish, Hebrew, German and other languages is an unprecedented enterprise. Its scale and level of complexity (in terms of content as well as basic organization) makes the translation and edition a unique effort on a global scale.

The work was appreciated by respectable institutions: in 2016, the translation team was awarded with the Polish Juliusz Żuławski PEN Club Prize, in 2017 dr Eleonora Bergman and prof. Tadeusz Epsztein received the Jan Karski and Pola Nireńska award, and one year later, dr Monika Polit received the Clio award for the edition of the 31st volume – The Works of Perec Opoczyński. The choice seems obvious. Thanks to their work, readers – not only academics – have received access to one of the most important sources for the history of the Holocaust in general, with a special focus on the history of the Holocaust in Poland. [1]

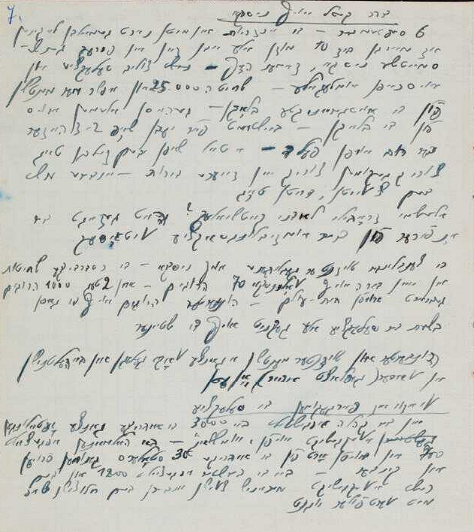

From the translators’ point of view, the work was very difficult, for various reasons. The documents were preserved mostly as manuscripts, written by many people, not only Emanuel Ringelblum’s regular associates. Reading them is a challenge due to handwriting (often rushed, on bad quality paper, with a pencil) and damage which affected the first part of the Archive. These documents span a large variety of subjects [2], written in many languages (mainly in Yiddish, but also in Polish, Hebrew, German and others), often intertwining, written also in various styles (from common speech to advanced religious writings). Their translation requires linking many competences, not only linguistic; it also requires extensive consultation and source research. When we add the necessity of identifying people, locations, events, decoding abbreviations, ciphers – we can imagine the scope of the challenge which the authors faced.

This is only an overview. We have to add convergence of terminology and annonations, necessary in the case of a multi-volume publication released over the course of several decades, as well as the pace of the project – the first volume was published in 1997, but after 2012, when the project received the grant of the National Humanities Development Program, several volumes were released every year.

It is difficult to convey all the obstacles and difficulties which emerged during translating and publishing subsequent volumes. This is why I decided to ask translators, editors and coordinators about their daily work, particular challenges they had to face, problems they encountered, and eventually – what was the biggest source of satisfaction.

We also have to remember that people who worked with particular documents were not professional translators, but academics, scholars, writers, archivists, employees of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute – who often dedicated their weekends, days and nights to this project.

When we listen to their words, even though they’re focused mainly on the practical side of translator’s work, the thought about the Editorial Staff as continuators of the will of the Archive founders comes to mind. Let me refer to the words of Prof. Jacek Leociak, who said in his eulogy during the PEN Club Prize ceremony: In my opinion, this award is being given to the entire great group of people, who had been working for years, and whom I would like to call, after Emanuel Ringelblum: ’Oneg Shabbat was a brotherhood, a company of brothers, who carried a banner of willingness to sacrifice and to remain true to the service to society’ (…) They committed to fulfilling the testament, buried in a basement of the 68 Nowolipki house, and spent days and nights over the documents, so that the letters could begin to speak. And they spoke. We give them our thanks.

The staff consists of 58 people – coordinators (dr Eleonora Bergman, dr Katarzyna Person, prof. Tadeusz Epsztein – scientific editor), translators involved in the works to various extent: some had translated vast amounts of text, while others took the challenge of translating particular, sometimes single, thematic pieces. [3] It took also a great amount of editorial work, because the complete edition has relied often on older translations.

I’m giving this work to you in a polyphonic form, one which conveys the nuances of this difficult, arduous work – yet it is work which everyone I am speaking to talks about with an enthusiastic blink in their eye. As you can see, there is no contradiction between these stances.

The conversations revealed several thematic areas, and this publication followed this division. It is dedicated to the Polish translation of the Ringelblum Archive, but let’s not forget that the English translation is pending – two volumes have already been published, followed by more of them soon. I have decided that this should be the subject of another story.

I would like to thank everybody who agreed to dedicate their time and attention. These meetings were informative and very heartfelt. I wish I could talk to everyone – unfortunately, time and circumstances didn’t allow for that. I have no doubt that despite the inquisitiveness and the vast array of subjects raised by my conversation partners, the topic hasn’t been exhausted yet.

Anna Majchrowska

-------------------------

[1] Feliks Tych in the foreword to volume 1, published in 1997, and translated entirely by Ruta Sakowska.

[2] The project involved translation of more than 35,000 pages of documents, spanning a vast array of subjects: accounts, diaries, memoirs, testaments, official documents, statistics, academic essays, literary works, press of the Warsaw Ghetto, press bulletins, religious writings, notes, reports, posters, flyers, letters, personal documents, surveys etc.

[3] The complete index of translators can be found at the end of the article.

Since the recovery of the first part of the Archive, nobody had any doubts that the documents should be published as soon as possible. Nachman Blumental, head of the Central Jewish Historical Committee, was writing about it already in 1946. In a report published by the same committee on 27 September 1947, we can read: ’we have to begin the publishing of documents from the Ringelblum Archive, because of their importance as documentary evidence’. The first printed versions of Emanuel Ringelblum’s notes were published as early as the following year. In the subsequent decades, editorial works continued, mainly in the JHI periodicals — ’Bleter far Geszichte’ and ’Biuletyn ŻIH’, as well as in several books. Altogether, only a small percent of the preserved documents appeared in print in the first three decades after the war. No comprehensive effort was taken practically until the late 1970s. In terms of research on the Ringelblum Archive, Ruta Sakowska had initiated intensive works in the 1960s. [1]

Katarzyna Person The first translations were made after the war. There were only few of them, but good quality, made by people embedded in their times. They knew it from their own experience, but also added a lot of their own. Sometimes we cannot tell why certain words had been deciphered the way they were. When we were publishing the writings of Emanuel Ringelblum, we have based on Adam Rutkowski’s translation from the 1960s (eventually published in 1983).

Joanna Nalewajko – Kulikov When it comes to translating Ringelblum, most of the work was done by dr Agata Kondrat, who compared the original with the Yiddish-language edition from the 1960s [2] and with Rutkowski’s version. The Yiddish-language edition proved to be very helpful, mostly due to the extent of preserved original and Ringelblum’s handwriting, which was difficult to decode.

Monika Polit The pioneering translators were Adam Rutkowski and Ruta Sakowska. They knew the context, didn’t have to consult anybody or find out about many things which for us are, and perhaps will always remain unclear.

Katarzyna Person A great example of complexity is Abraham Lewin’s Diary. We’re using Rutkowski’s translation from the 1950s as the basis, we verify it – we add fragments removed by Rutkowski for various reasons, and add writings sent after the war to YIVO by Hersz Wasser. On the other hand, in the 1950s translation, there are two large fragments which were lost after the war and we don’t have access to the complete original – we have to rely on Rutkowski’s work. We also have to be aware that these writings were subject to censorship on at least three levels – political, due to dynamic situation in Poland and unclear status of the JHI at that time; preventive censorship was applied by all institutions in Poland back then. Censorship was also related to the fact that the JHI was trying to shape the memory of the Holocaust and about the attitudes of the Jewish community during the Holocaust. This is very interesting, because different censorship is applied in the Yiddish and in the Polish versions, which has to be considered if we want to utilise these translations today. Third layer of censorship is related to the memory of war in general, not only in Poland. I mean here psychological, social issues, the way the experience of women was described after the war. Thiss is an issue not specific only to Poland and to the Jewish community, parts which referred to sexuality were being removed from Polish and Jewish documents worldwide. Many excerpts had been removed from postwar translations, but at the same time these changes were not marked, or marked as unclear. Sometimes the reader was indirectly informed about censorship through a statement that for example a fragment was unclear.

Joanna Nalewajko – Kulikov There were less censored fragments in Ringelblum’s writings that one could expect. It is also interesting that the Polish edition was more censored than the Yiddish one. There are omissions in the latter as well, but they stem for example from a mistake made by a typesetter. In the 1983 Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto, the fragment about Witkacy committing suicide after the aggression from the Soviet Union was removed, whilst in the Yiddish version, it wasn’t. Maybe because it was aimed at a different reader?

Agnieszka Żółkiewska These texts had been modified many times after the war for many reasons. Even in such innocent writings as poems, translators or editors didn’t accept the truth which they carried. In order to avoid controversy, too brutal excerpts describing the ghetto reality, or related to human body or sexuality were sometimes removed. But smoothing the text meant automatic smoothing of reality, which was much more complex than it may seem. Ringelblum was caring about compliance of the Archive documents with his very high standards. A special committee comprising several people was reading the texts before Ringelblum confirmed them and accepted into the Archive. In fact, many texts which seem more controversial from today’s point of view than today, had been accepted. Ringelblum was thinking ike a historian who wanted to convey the reality in a possibly objective way. Ghetto was his reality, so he didn’t have the problems which postwar Holocaust historians, especially in Communist Poland and East Germany, were struggling with. We can’t be fully sure whether it was their personal issue or rather one specific to the political reality which had a strong impact on them.

Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov In the case of Ringelblum’s writings, Rutkowski’s translation sounds a bit archaic, certain phrases are not in use anymore, or things are said differently. Agata Kondrat delivered the translation in a raw form, as it was agreed, and I was wondering whether it should be more polished, if I have the right to modify the language used by Rutkowski, who came from the same background as Ringelblum – Polish-Jewish intelligentsia. I assume that Ringelblum’s Polish was closer to the language used by Rutkowski than contemporary one. Eventually I decided that this translation would have sounded archaic today. It would be different if it was the original text. But a translation has to be clear for readers today. Also, the older translation was Christianised, with Easter instead of Pesach and Confirmation instead of Bar Mitzvah. This is not practiced today.

--------------------

[1] Tadeusz Epsztein, Pełna edycja dokumentów z Archiwum Ringelbluma, Kwartalnik Historii Żydów, nr 4 (264), grudzień 2017.

[2] Emanuel Ringelblum, Ksowim fun getto, 1939 -1943, Idisz Buch, col. I, Warsaw 1961, vol. II, Warsaw 1963.

The works on the first volume began in mid-1990s. In 1995, Ruta Sakowska prepared a concept of dividing the documents from the Archive into particular volumes of the future edition. In 1997, the first volume of the complete edition was published, and in a short time, two following ones were ready to print. In order to accelerate the editorial works, Feliks Tych, director of the JHI since 1996, decided to decided to prepare a new inventory of the collection in the first place, assigning the task to a team led by professor Tadeusz Epsztein. Preliminary works have begun in late 2000. In Spring of 2001, first archive indexes of documents from the first part of the Archive were introduced. In May 2003, the indexes for the inventory were ready. Between 2009 and 2010, last additions and corrections were introduced to the inventory in Polish version. In early 2007, dr Eleonora Bergman took the position of the director of the JHI and began to form a new editorial staff. [1]

Tadeusz Epsztein I wouldn’t have taken this challenge without Ruta Sakowska. She had taught me many things, introduced me into the specifics of the Ringelblum Archive, taught me to notice various problems in documents, encouraged me to learn the basics of Yiddish. She signed only few texts as a translator, but it can be misleading – she was also proofreading documents translated by others. Her contribution was significant.

Eleonora Bergman The first volume of the complete edition of the Ringelblum Archive was composed by dr Ruta Sakowska. The idea to begin with documents which speak on the human level the most, such as private letters, microhistories, was hers. The second volume – documents about children and their stories – was her own idea too. Materials for the third volume were selected and arranged by professor (then – still doctor) Andrzej Żbikowski, who was interested in the history of the Eastern Borderlands after the outbreak of World War II. The fourth volume, dedicated to the works of Gela Seksztajn, was edited by Magdalena Tarnowska, according to her own interests.

The base of the new inventory which prof. Epsztein was working on was ready already in 2000. I have already been strongly engaged in these efforts and I came to a conclusion that with inventory, we could approach the planning of the new edition differently. We have begun from volumes dedicated to territories (including documents related to the entire territory of Poland occupied by Nazi Germany: aside from Eastern Borderlands, the General Gouvernement and areas incorporated into the Third Reich) edited by Marta Janczewska, under supervision from Ruta Sakowska.

Tadeusz Epsztein The person who encouraged me to join the works on the complete edition was dr Eleonora Bergman. It is our shared project. The most difficult challenge was to organize a network of translators. It was very difficult, even though I had contact to many peeople who were helping with translations from Yiddish and Hebrew during the work on the inventory. Still, that required basic information, whilst here, we needed comprehensive translation. We relied mainly on Sara Arm, but she wasn’t able to deal with such an enormous amount of documents alone. She was cooperating with us all the time, until the end.

Sara Arm I have heard about the project first at the corridor of the Jewish Historical Institute a long time ago. Michał Friedman said that we have to begin translations of the Ringelblum Archive. I was aware that not many people in Poland knew what it was. I thought: I have to translate it! I was looking forward to working on something I consider very important.

Eleonora Bergman In 2007, we had begun to plan the complete edition with Tadeusz Epsztein. We had been collecting funds, but differently – for selected materials. At that time, the inventory was being printed in Washington. We have made a table including all the materials from the Ringelblum Archive, with an annotation about the type of material and other basic information. At the same time, we managed to receive a grant from the Foundation for Polish Science – which allowed us to work on the „territorial” volumes. Thanks to funds from the Polish-German Cooperation Foundation, we could have begun to work on regular translations. These processes were happening in a parallel way. We began to search for translators, to built a base of people involve in the project. Because parts of the material had already been translated by Sara Arm in cooperation with „Karta”, vol.5 (Warsaw Ghetto, the daily life) could have been published quite quickly. A lucky coincidence was also the establishing of the Polish Society for Yiddish Studies, where some of our translators come from — Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Bella Szwarcman-Czarnota, Agata Kondrat, Agnieszka Żółkiewska, Marek Tuszewicki, Karolina Szymaniak and others. It was a real breakthrough when it comes to translations – it turned out that there emerged an entire group of people who could join us, also Monika Polit and Marcin Urynowicz. An additional helpful factor was the fact that since 2008, everybody was able to work on scanned documents. It was a phenomenal coincidence. When we applied for funds for the complete edition from the National Program for Development of Humanities in 2012, it was clear that we had translators and editors for next volumes.

Magdalena Siek For several years, the work had been very intensive, because we were moving fast. There were never enough translators, initially the work was done practically only by Sara Arm. Sara was responsible for translations to volumes edited by me – 8 and 9. Because they relied mainly on manuscripts, it was good to have someone else to look at the text in order to resolve unclear situations, add corrections. This is how I became involved. While working on the editions of my two volumes, checking Sara’s translations and comparing them against the originals, I became familiar enough with the text to move on towards other translations.

Tadeusz Epsztein We were in a hurry because we assumed that we will prepare a complete edition. In the planned volume, we had to include all the documents related to a particular subject. The main challenge were translations from Yiddish because they make the majority of documents. We were looking for translators in Poland and abroad. Many people didn’t want to work on manuscripts – and we had mostly manuscripts or typed text which was also damaged, which required excellent knowledge of the language.

Eleonora Bergman Among the JHI employees, Piotr Kendziorek was responsible for translations from German, Magdalena Siek did a great job with translations from Yiddish. This is how the group working on the Archive kept expanding. Most of the members remained there, in various configurations, until the end of the project. The same translators, while working on following volumes, had to work on a variety of themes which required not only the knowledge of the language but also of the conditions of described reality. There were also contributors, mainly from the Polish Society for Yiddish Studies, who were also providing single translations.

-----------------

[1] Tadeusz Epsztein, Pełna edycja dokumentów z Archiwum Ringelbluma, Kwartalnik Historii Żydów, nr 4 (264), grudzień 2017.

Magdalena Siek The documents in the Archive are very diverse. Literature, official documents, reports, everything written differently. Not everybody who is a good belles lettres translator understands well the historical context.

Marek Tuszewicki Aside from literature – belles lettres or works arpiring to this name, in volume 26 (Literary works from the Warsaw Ghetto) we can find texts collected on the street, ethno-humor, jokes, folk songs and even legends. They all fall into a separate category of a resource and as such, they’re very interesting due to providing an image of a community closed in a ghetto, especially covering the groups which were hardly given their voice: orthodox Jews, or Jews who were simple and didn’t know much Polish. Their various beliefs, myths, symbolic links to the way they experienced the world and religion are very interesting. Their presence in the language of facts, of parallel war events is striking. Their awareness of battles in the Far East or Northern Africa may surprise when we take into consideration the fact that they were closed in one district of Warsaw. It breaks the vision of the ghetto as a place cut off from the world, separated from reality.

Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska I was translating pre-war textbooks written by Kalonymus Shapiro, a tzadik from Piaseczno, addressed at hassidic youth beginning their mystical way of Judaism. It was an attempt to protect the youth from the allure of the outside world, to bring back a dimension of Hassidism which would be attractive to the young audience.

Monika Polit I am from Łódź and I’m researching the subject of the city as well, hence the first volume edited and translated by me was dedicated to the Jews of Łódź. The Ringelblum Archive was collecting documents written in Łódź in 1939 and early 1940. Many inhabitants, or rather prisoners, of the Łódź Ghetto – mainly clerks but also acolytes of Mordechaj Rumkowski – escaped to Warsaw and took important documents from the period right before and after establishing the ghetto. These are mainly official announcements, but also personal documents: reports, stories. I was interested in them due to my work, so the goal was both practical and holistic – I wanted to complete the publications which I had been working on before with knowledge from the Ringelblum Archive. This is how it all began.

In case of the volume dedicated to Perec Opoczyński, a few years earlier, at Barbara Engelking’s request, I worked on Perec Opoczyński’s Press Stories – a choice of the best articles in his work as a journalist and reporter. Due to this, it became natural for coordinators of the complete version of the Archive that I could also work on Opoczyński’s legacy.

Piotr Kendziorek The documents in German were both official announcements (published by the Germans or by the Jewish Councils) and personal documents – stories or letters, because there was a law according to which letters had to be sent in German. The latter could be divided into two categories: letters written by native speakers, mainly Jews from Austria, Germany or Czech Republic, people who spoke German well. There were also letters, applications, formal documents written by Polish Jews, with mistakes, problems with grammar, unusual constructions, cliches from Yiddish.

Eleonora Bergman Majority of documents in the Ringelblum Archive are in Yiddish, the rest – in German and Hebrew. In the volume on Eastern Borderlands there appears also Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, which shows a certain specific nature of communication in that area. Translations from Hebrew proved to be a very difficult job, such as in the case of pre-war short stories by Perec Opoczyński. Majority of contemporary Israelis simply don’t understand them. We know a little about the evolution of Hebrew, but it was shocking to discover that they simply cannot understand language from a few decades back. Thankfully, Agnieszka Jawor-Polak, Daria Boniecka-Stępień i Karol Becker came to the rescue.

Tadeusz Epsztein Another issue which we weren’t fully aware of was the fact that Yiddish is a very complex language, comprising various dialects, for example the writings of rabbi Huberband have a parallel Hebrew layer. The Hebrew vocabulary is related to the cultural circles he belonged to, the educated, religious people. It is a layer in which a translator who knows only Yiddish or only basics of Hebrew won’t understand at all. Ania Ciałowicz, a very competent translator, was working on Huberband and put a lot of effort into this work. A priceless contribution came from Blanka Górecka, an expert on Hebrew, with a great knowledge of Jewish religious culture. The translation may be correct but it would lose a lot without commentary, the second, very important layer wouldn’t be visible without them.

Other pieces of text required translators who could feel the common speech, often appearing in the personal accounts. Sara Arm and Ruta Sakowska grew up in Yiddish-language culture, have been learning the language as children and could feel it, notice nuances. They would say: it is not like this! It’s something different! For somebody young, such nuances are invisible. The press was also a big translation challenge. Another topic are Hebrew translations. It may seem against logic, because it is a functioning language, so we should have been able to find translators – yet it proved to be a challenge. Some people were working with us long-term, such as Agnieszka Jawor-Polak, who delivered a high-quality translation of Opoczyński’s short stories. Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska and Regina Gromadzka have translated an extraordinarily difficult piece, the writings of rabbi Shapiro.

Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska It was a great challenge for me, difficult, but professionally very important. Kalonymus Shapiro’s works are special for many reasons – linguistic, literary, but also for research. They’re written in rabbinical Hebrew, rarely encountered by contemporary Hebrew translators, often difficult to understand for contemporary Israelis. There also fragments in Yiddish and Arameic. The writings deal with phenomena which are not present in the Polish microcosm, we’re not familiar with Jewish mysticism, so we have to find a new approach in Polish. I owe a lot to professor Maciej Tomal, who supported my work.

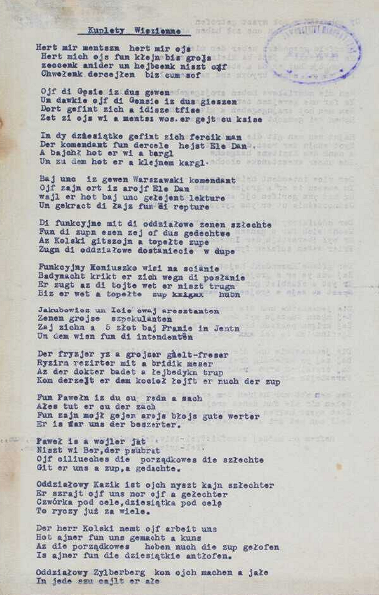

Agnieszka Żółkiewska The majority of literary works published in the 26th volume of the complete edition have seen the light of day for the first time. It’s also a pioneering translation in Polish. What facilitated our work in terms of writings in Yiddish was the closeness to the Polish language. In works written by younger associates of Ringelblum, Polish appears often, sometimes in a surprising way, mainly as neologisms which didn’t exist in Yiddish previously. For example Skałow – it was a pseudonym used by writer Lejb Truskałowski – created a number of new words, verbs such as kurczen zich (to shrink), or more obvious ones, like dlonies (hands), slojez (jars). His Yiddish is deeply tooted in Polish, we can see that these words were appearing inadvertently, that he was functioning in both languages.

The intertwining between these languages can be seen in such a surprising work of literature as the Prison couplets — it’s written in Yiddish, in Latin alphabet, bbut if we take a closer look we can see Polish influence. It was written in Gęsiówka, the famous prison in the ghetto, where people speaking various languages met, and their languages would mix.

Languages in the Ringelblum Archive appear also in a comical manner – a play on Yiddish and Polish and relations between them appears in Jurandot’s comedy, Love lookign for an apartment. The play confronts two groups – Polish-speaking and Yiddish-speaking, there is also a „test” of the knowledge of Yiddish for the Polish-speaking group. It is linguistic humor, specific for the Warsaw Ghetto. One has to know the circumstances to understand it. The text can be fully understood and reveal itself as playful when someone knows both languages. Jurandot’s comedy is also a document of relationships between assimilated and non-assimilated Jews in the ghetto.

Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov Texts from the Archive are very demanding for a translator. They were written by ordinary people, sometimes in the same way as they were speaking. They didn’t consider that they may be read one day by someone speaking a different language, not knowing vocabulary specific to a profession or location. One needs general knowledge about the ghetto reality in order to understand what they were writing about. There’s a couple places in the Ringelblum Archive where we’re not sure what was the meaning. Some fragments were written in a code, but there are also words which previous translators struggled with, such as the word „asurejka”, which is underlined – from that we know that others had difficulty translating it too. Even in the version in Yiddish, there’s a square bracket with a quotation mark. We know it refers to some kind of money collecting but we don’t know details. In