- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Marek Tuszewicki My work on the Archive was twofold. Together with Agnieszka Żółkiewska, I was editing the volume dedicated to literature. I was involved more strongly in work on this volume. Translating literature is completely different than documents from my previous volume about the countryside. I receive and sense it in a different way. There also appears the question of elements of art and attempts to convey not only content and strong emotion but also artistic shape of what was written. The project of the literary volume was important for me not only due to the Archive itself but also due to what I could experience. On the other hand, translating historical testimonies which don’t carry so much cumulated emotion as literature does, is actually documentary, archive work, which involved turning pages of history and making them legible for contemporary reader again. I see myself there more like a custodian than a translator of literature.

Piotr Kendziorek Translating personal testimonies means dealing with horror. It is a litany of unimaginable suffering. I have been especially moved by accounts of the Jews who were subject to forced labour on labour camps, in which Poles were often working as guards. The Jews were often being tortured and robbed. I remember it being shocking to me – the cruelty often was driven by greed, but sometimes it was happening for no reason, simply as the norm. One has to find language to convey such horror, but a translator should not introduce words stronger than the original – their job is to mediate the intention of the author.

Personal documents pose different problems than official ones. It hardly ever happened that I had no idea what they were about. But there always appears a question whether the Polish translation should also include linguistic imperfections, mistakes, as in a translation true to the original? Or would a reader think that I have confused something, and everything would require a footnote? With smaller mistakes, I was trying to simplify, and in case of serious ones, I tried to explain. For a translator, it is a question of balance between clarity, conveying the original and not burdening the reader with footnotes. There is also a question of numerous repetitions – what if something is written correctly, but the author had a tendency or habit to repeat the same word in two sentences? It doesn’t sound too well. Also, what in the case when a translator cannot find a Polish equivalent? I have to admit I haven’t come across a case like this. There’s a principle according to which one doesn’t translate what they don’t understand. Even if something doesn’t make sense, we have to ask ourselves: why does it lack sense? Why did someone do something illogical, make a mistake? What may have been the reason? In general we have to assume that if we don’t understand something, we are making a mistake.

Agnieszka Żółkiewska Another problem encountered by translators, especially translators of literature, is the fact that their authors were never given a chance to correct, perfect, polish them. This leads to various dilemmas – how to convey the writing with an advantage to the author? If something was unfinished, or had certain logical or stylistic shortcomings, we had to make decisions. Such situations are difficult for translators who don’t want to interfere with the text and correct the author. But such interferences never modified the meaning.

Those from Ringelblum’s associates, who had experience with literature, some of them were working as journalists before the war – were luckier than their fellow writers in the ghetto, because they were receiving a certain minimum payment for their work. They approached their profession with commitment and it can be noticed in their writings – the reality is being described in detail, with empathy, and with criticism directed at those who lacked empathy towards the tragedy of the ghetto. This is a new, fresh challenge. We’re used to a non-Jewish perspective, to seeing the Holocaust through the eyes of non-Jewish witnesses who had never experienced the ghetto. We have a reverse perspective, seeing Warsaw Ghetto from the inside, through the eyes of people trapped there. It was also a challenge for us translators – it provides a different picture of the ghetto, full of martyrdom, very moving, but also delivering an image of very complicated conditions.

Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska I have been working on my translations for nearly three years, including weekends, days and nights. I remember it as a very exhausting experience.

My experience so far shows that no kind of reading, academic or for one’s own, never provides such a deep bond with the author as reading for the purpose of translation. I see things I haven’t noticed before, and this provides another dimension to my experience.

Monika Polit A translator is someone who is skilled in the craft of, I would say, artistic translation. One can perform this job because of necessity, for example for research. It’s hard to call any of us a professional translator, for none of us this is primary occupation. We perform it occassionally, but with no smaller attention. Quite the contrary.

What links us to professional translators is the fact that we keep returning to words, revolve around them, look carefully at anything unclear, unreadable. Eventually, a word which seemed originally like an ink blot, becomes obvious after revisions and working with context. Sometimes, we only assume the meaning, or we realize that no other one suits there. Some of us were also editors, which meant working both on translation and editing. This requires a completely different approach. We have to deliver material to linguistic editors in a form which won’t pose difficulties until the moment of publishing, we have to be ready to answer any question related to our academic and editorial background.

Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska This work has taught me a lot. Humility is an important quality for a translator – we never know what to expect when we begin work, even if we read the text before. It brings great satisfaction, a lot of stress, and carries a lot of responsibility towards the author, readers and researchers, as the text can be used as resource.

Monika Polit My personal experience with this work is meditational. As a very impatient person, I have a chance to become methodical and careful while working on manuscripts, I slow down my thoughts and actions. Translation is a linear process. It makes me stop, settle, provides quiet, peace and distance. First of all, it is related to the matter or working with manuscripts, but secondly – they’re usually exceptional literature or works of art, so I pay attention to deliver every word correctly, without twisting the meaning.

Tadeusz Epsztein I can remember a moment when we were beginning. Thousands of documents were waiting to be translated, and it was a dream to find at least a few translators. We were desperately searching across Poland. I was sitting and my computer, sending emails, asking people to deliver anything. We really wanted it all to begin. This edition wouldn’t exist were it not for translators. It wouldn’t be possible without them.

Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska Coordinators of the project deserve great respect for the enormous work they’ve done. It seems like a miracle that we manages to complete it, and in such a form. All the volumes are perfectly edited, the team maintained quality until the very end. I don’t knowif anyone else would be capable of doing this. I appreciate the determination and would like to emphasise the importance of this work for us all, not only future generations, but also for us translators, through creating convienient conditions for us to work in. We could have always counted on their support, regardless of how many of us were at work. They were an enormous sea of people to guard, manage, help, who have their needs and particular project, specific language, nature of translation – it was an incredible job.

Monika Polit I am satisfied, but I’m not always pleased – every time I take a look at my translation again, I can point at a place where I could correct something. But I believe it must be natural. One has to keep going, keep working, without conviction that the work is done. Something which seems certain now, may be revised or corrected in the future, maybe by a native speaker or someone with an education similar to the authors of the Archive. This would allow for noticing subtleties which we’re unaware of and spot mistakes in our thinking.

Agnieszka Żółkiewska Working with documents from the Ringelblum Archive was a different challenge for everybody, even though we have all felt deep emotions about them. It is unavoidable during work with Holocaust-era documents. In the case of writings in Yiddish, we were aware that they were one of the last things written in this language in Poland – the language was killed along with people who spoke it. Now, the last Jews who were brought up speaking Yiddish are passing away. This is why we felt the great responsibility, and we were also aware that Oneg Shabbat were linked by a sense of mission to tell the whole world about what was happening in the Warsaw Ghetto. We wanted to perform our task the best we could.

Sara Arm I was simply translating human fate. The fate of these people, this is what I had in mind. The world should know and remember about them. This is why I agreed to this commission. I didn’t want to be the only one to know. I didn what I could. I was sitting over these documents day and night. It was really difficult. I have lost touch with many friends because I was spending all my time on it. Some things were really shocking for me and I was talking about them, but nobody wants to listen, especially if they’re not interested.

Of all things I have done, this was the most important for me.

Tadeusz Epsztein When we began work on editing the documents, there were various ideas on how to approach it. We had no doubts that we had to follow the intention of Ruta Sakowska, already in the 1970s, to make the documents alive, functioning. This required translating to Polish and later also to English. We knew that if they’re not edited, translated and shared, people won’t reach for them, and all this heritage will remain safe but useless. These resources have an importance which reaches beyond the realm of professional history. I don’t want to sound pompous, but we had a task to make it public, not only for people who speak these rare languages.

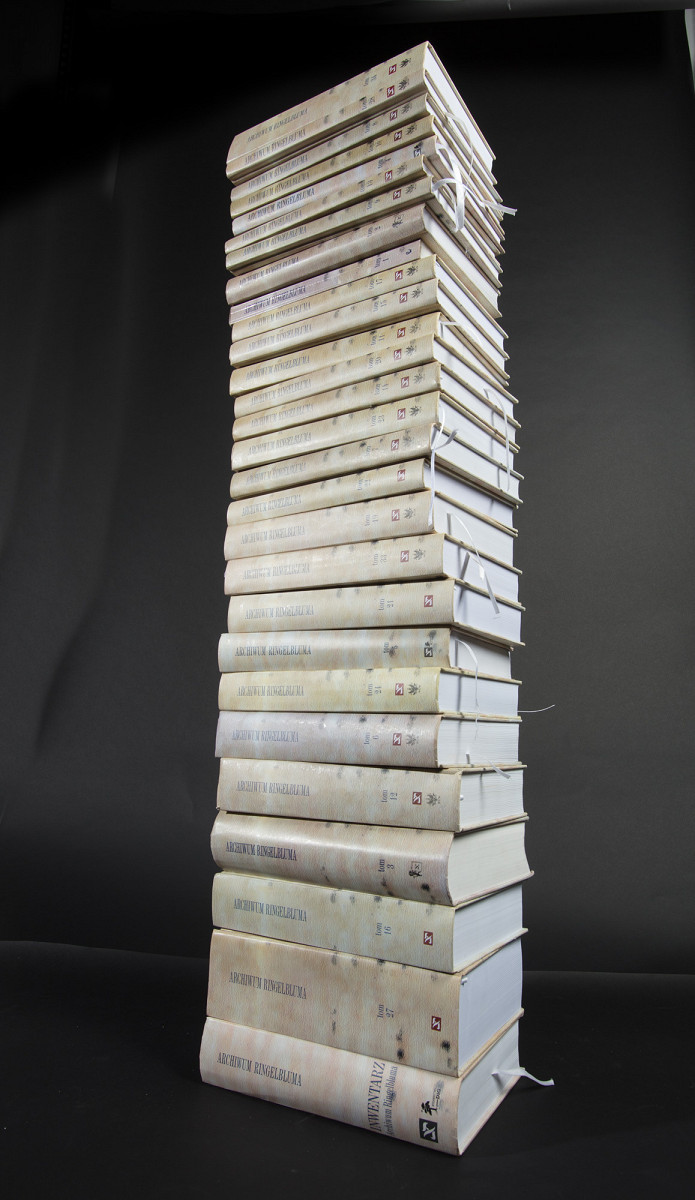

Full edition of the Ringelblum Archive

I would like to thank everybody who contributed to this edition, especially my conversation partners: coordinators and scientific editors of the complete edition of the Ringelblum Archive — dr Eleonora Bergman, dr Katarzyna Person, prof. Tadeusz Epsztein and translators — Sara Arm, Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, dr Piotr Kendziorek, dr hab. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, dr Monika Polit, Magdalena Siek, Bella Szwarcman-Czarnota, dr Marek Tuszewicki, dr Agnieszka Żółkiewska.

------------------

Complete list of translators of the complete edition of the Ringelblum Archive, in alphabetical order:

Sara Arm, Aleksandra Bańkowska, Małgorzata Barcikowska, Tatiana Berenstein, Eleonora Bergman, Daria Boniecka-Stępień, Iwona Brzewska, Anna Ciałowicz, Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, Tadeusz Epsztein, Joanna Feldman-Kwiecień, Maria Ferenc Piotrowska, Michał Friedman, Maja Gąssowska, Aleksandra Geller, Alicja Gontarek, Blanka Górecka, Regina Gromacka, Julia Jakubowska, Agnieszka Jawor-Polak, Piotr Kendziorek, Michał Koktysz, Agata Kondrat, Iga Monika Kościołek, Shmuel Krakowski, Jan Leński, Tadeusz Lewandowski, Joanna Lisek, Izabela Łach, Justyna Majewska, Piotr Matywiecki, Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Agnieszka Olek, Zofia Pacuska, Kazimierz Pacuski, Katarzyna Person, Monika Polit, Yale Reisner, Martyna Rusiniak-Karwat, Adam Rutkowski, Ruta Sakowska, Jacek Sawicki, Magdalena Siek, Alina Skibińska, Anna Szyba, Karolina Szymaniak, Bella Szwarcman-Czarnota, Sylwia Szymańska-Smolkin, Magdalena Tarnowska, Maciej Tomal, Marek Tuszewicki, Marta Tycner-Wolicka, Marcin Urynowicz, Maciej Wójcicki, Franciszek Zakrzewski, Olga Zienkiewicz, Andrzej Żbikowski, Agnieszka Żółkiewska.