- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

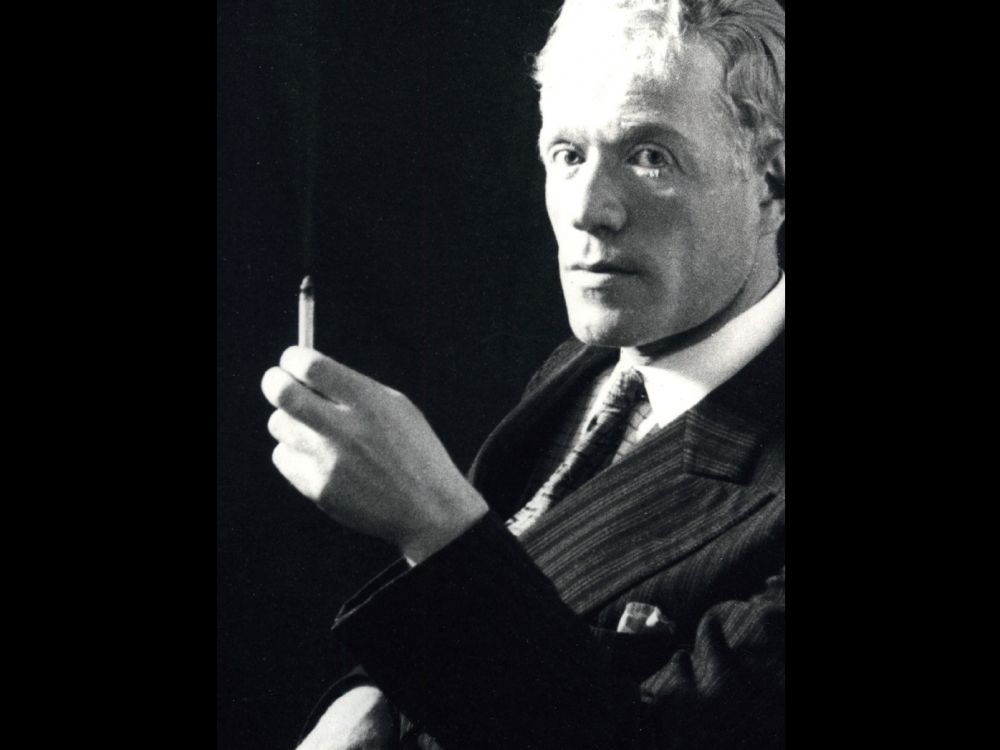

Symcha Trachter after returning from Paris in 1929. Photo taken in Lublin by Wiktor Ziółkowski / Hieronim Łopaciński Provincial Public Library in Lublin

Between 1900-1914 and 1918-1939, artists from all across Europe would head to Paris. A particularly large group arrived from the Slavic countries, especially Jews from Central and Eastern Europe; among them, there were such outstanding names as Marc Chagall, Jules Pascin, Chaim Soutine or Ossip Zadkine1. Trachter’s decision to go to Paris could have been prompted by contact with Józef Pankiewicz’s students at the Academy of Arts in Kraków2, who believed in their mentor’s statement that every artist should attend the „Paris school” in order to get to know the Impressionist foundations of painting3.

The goal of the travel were also museums and galleries presenting the old masters, the Louvre above all. Young artists from Kraków didn’t pay attention to the modern art movements developing in Paris at the time. They rather believed that the capitol of the Republic didn’t change much since the 1870s or the 1880s. The Kapists (Polish acronym for the Paris Committee), encouraged by Pankiewicz, went to Paris in the Autumn of 19244. Trachter followed almost one year later. The city impressed the young painter immediately. He absorbed the atmosphere of the streets, mixed in with the crowd and celebrated 14th of July with Parisians5. Like the Kapists, he often visited museums, especially the vast Louvre6.

![1918,_Soutine,_Self_Portrait_wiki.jpg [308.80 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/22/d5f37477672cb3046caaec2e29cf65a1/jpg/jhi/preview/1918,_Soutine,_Self_Portrait_wiki.jpg)

At the beginning of his stay, he wrote in a letter to his friend Wiktor Ziółkowski about his room and its location: „I live very far away from the academies, every day I travel almost half an hour by metro. My room is near Montmartre – on the 5th floor, and it’s very nice”7. Later, he moved to the city center, to rue Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie 398.

After their arrival on the banks of the Seine, young adepts of painting usually enrolled in private art schools in the Montparnasse district, called, with certain exaggeration, academies. Trachter was studying at Académie Ranson with Roger Bissière, but the professor didn’t leave a strong impression on him9. It seems that the artist from Lublin had learned more observing Parisian painters in their ateliers and visiting exhibitions.

How a Central European painter of Jewish origin lived in Paris? We can learn about it from Cecylia Słapakowa’s article based on a conversation with Emmanuel Mané-Katz, conducted for the „5-ta Rano” [5 AM] magazine in 1937. It was written several years after Trachter’s stay in Paris, but it proves the significance of the city for painters who had found themselves in a similar situation to the artist from Lublin, and it explains how the 1930s intellectual understood it.

„What is contemporary reality for Jewish artists like in Paris? – I ask Mané-Katz. – Paris is a true homeland of painters, the center of global art. The museums, galleries, private collections contain the greatest works of painting. The possibility of confronting one’s own art with others’ works prompts self-criticism, constant self-control, moving forward thanks to comparison. Paris is «the toughest and the lightest» city in the world at once. Probably nowhere else can an artist feel so good and so free as on the banks of the Seine. Among Jewish painters, only a small bunch achieved fame and fortune, usually they live in poverty, just like their non-Jewish peers. The misery of many artists who arrive in Paris is the fact that they, on their mission to merge with the new milieu, lose their self, at the same time not reaching towards the French culture either – and they end up lost for their entire life, without support and secure ground. Only those who enjoy sponsorship can survive in this hopeless situation, they can work successfully, but they don’t pay any significant role in the history of painting. Their paintings are weak, they don’t sell well, they never reach above mediocre level. But those who assimilate the best elements from French and global art culture maintain their individuality, climb onto the Parnassus, enjoy global fame. The actual talent – says Mané-Katz with certainty – cannot be lost. An artist who has something to say will always do so. And if it’s a really outstanding artist, their name will go down in history.

Paris allows every artist to speak out. It is special and great precisely because it refuses to segregate art by nation. An artist’s origin doesn’t matter, only talent and creative personality matter.

![Paryż_zaułek_NAC_comp.jpg [645.88 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/22/de561bb6b0286a8efeb855d5823de204/jpg/jhi/preview/Paryż_zaułek_NAC_comp.jpg)

Certain groups of talentless French artists are trying to cause a stir, agitating towards special support for local artists, but without much success – Paris focuses primarily on the human being, a humanitarian spirit prevails over nationalism. Museums are buying works by Jewish artists and organizing collective exhibitions of French and Jewish painters; those painters who cannot sell their works can apply for support for the unemployed, granted by the government to the French as well as to the foreigners. Hence, Jewish artists living in Paris are devoted French patriots. When Mané-Katz says: «we all adore this country, because it allows us to develop our talent, because we can feel free here and can be as creative as we wish» – his words resonate with oble pathos of true adoration and nearly childlike enthusiasm, and perhaps this is why they carry a moving charm of freshness, the smell of Champs-Elysees and the cool wind from the romantic Seine”10.

Like for Mané-Katz, also for Trachter Paris was a place of confronting his own oeuvre with the works of others. This constant comparison led to self-criticism and search for one’s own language, something new and original. Trachter was complaining about this struggle in his letters: „I have just got to know two greatest painters of the 20th century [Paul Cézanne and Auguste Renoir – J.B.]. Like great artists, they suffer and can never be sure of their skill”11. Trachter was looking for inspiration and compared his work to the works of other painters in the museums, exhibitions and salons of Paris. He visited Rodin’s Museum, as well as the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts and Design in 192512. He was also visiting teh studios of Eugeniusz Eibisch and Tadeusz Makowski: „I have recently seen Ejbisz’s works, they’re quite sincere and he keeps making progress, but for Paris, they are still quite poor. Mr Zborowski, an art dealer, pays him 1500 francs a month. Ejbisz’s friends think he’s very good, I also believe so”13. He also saw paintings by other Polish painters, such as Roman Kramsztyk or Eugeniusz Zak, as well as by André Derain, Charles Dufresne and Chaim Soutine, about whom he wrote with respect, and eventually also with admiration14. He maintained interest in the commercial side of art; he was finding out about the prices of paintings by artists important for him, such as Soutine or Amedeo Modigliani: „Have you heard of Sutin? He is very famous in Paris right now, everyone talks about him. They say he is the greatest artist of the younger generation. A few years ago, he was completely unknown, now they pay for his paintings 50000, 10000 fr. I like his works a lot, he is quite a turbulent artist, with a great visual talent. For Modigliani, they pay a lot too”15.

In her article, Słapakowa accentuated the cosmopolitan nature of interwar Paris, where nationalism could have been encountered only rarely. In the art world, nobody usually paid attention to the origin of the artist. It is difficult to tell whether it was one of the factors behind Trachter’s move to Paris. In his preserved letters, he doesn’t mention the subject at all. In Poland, he didn’t have any problems with presenting his works. He didn’t complain about the relations at the Academy of Arts in Kraków either.

![trachter_vence_1a.jpg [351.29 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/22/db45912d09f5866dffd8ca20dd6cfdce/jpg/jhi/preview/trachter_vence_1a.jpg)

Despite his family’s material support, good atmosphere and numerous factors motivating him to work16, Trachter couldn’t or didn’t want to stay in France. Was he afraid of losing his own self, as Słapakowa wrote? That’s not likely, or at least, no source mentions it. It even seems that after his stay in France, the painter gained self-confidence and even critical of other artists. Perhaps the reason might have been jealousy of the successes of others? Or maybe simply he was missing his family and familiar places, and became weary of loneliness? Before Trachter returned to Poland, he went once more to Southern France, to Provence, charming with its sun and colours. He traveled there in late February 1928, joining Eugeniusz Eibisch and his wife Franciszka, who stayed in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, on a high hill. The painter fell in love with the town and its nature17. He also felt comfortable in the company of Eibisch, a fellow Lublin painter. The trip resulted in a number of landscapes depicting the location and its surroundings18. One of them had survived until today19 – it is very similar to Eibisch’s painting made in the same place, at the same or similar time20.

The article is an excerpt from the publication Trachter. Malarz z Lublina [Trachter. Painter from Lublin], accompanying the temporary exhibition at the Jewish Historical Institute.

The exhibition Symcha Trachter 1894-1942. Light and Color can be visited at the JHI until October 25, 2020.

![granty_norw_EN.jpg [39.66 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/1/b5c2e62f4995b8a22f0d0e59a1673d2a/jpg/jhi/preview/norweskie_EN_do_2021.jpg)

The exhibition is financed by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway from the EEA Grants and the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage

Footnotes:

1 L. Lameński, Rola Paryża w rozwoju malarstwa polskiego XIX i XX wieku, [in:] Idem, Moi artyści, moje galerie. Teksty o sztuce XIX i XX wieku, Lublin 2008, p. 66–68.

2 Trachter wrote in a letter to Wiktor Ziółkowski soon after his arrival in Paris: „I have met a few of my colleagues from Kraków, there are so many painters from Kraków here that it seems as if nearly the whole local art world moved to Paris right now” (a letter to W. Ziółkowski, 25 May 1925, Korespondencja WZ, p. 87–90). Here, and in several other places, the transcription was simplified in comparison with the original letter.

3 Andrzej Turowski, Nurt koloryzmu w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym, [in:] Dzieje sztuki polskiej, ed. Bożena Kowalska, Warsaw 1987, p. 206.

4 Ibidem.

5 Letter to W. Ziółkowski, 22 July 1925, Korespondencja WZ, p. 91–94.

6 Postcard to W. Ziółkowski, 12 April 1925, Korespondencja WZ, p. 85.

7 Letter to W. Ziółkowski, 25 May 1925, Korespondencja WZ, p. 87–90.

8 Postcard to W. Ziółkowski, 1 November 1927, Korespondencja WZ, p. 95.

9 Letter to W. Ziółkowski, 25 May 1925, Korespondencja WZ, p. 87–89.

10 Cecylia Słapakowa, Godzina z Mane Katzem, „5-ta Rano”, 20 V 1937, p. 7.

11 Letter to W. Ziółkowski, 22 July 1925, Korespondencja WZ, p. 91–94.

12 Tamże.

13 Letter to W. Ziółkowski, 22 December 1927, Korespondencja WZ, p. 98–100.

14 Postcard to W. Ziółkowski, 15 January 1929, Korespondencja WZ, p. 105.

15 Letter to W. Ziółkowski, 22 December 1927, Korespondencja WZ, p. 98–100.

16 Author of a press note Malarze lubelscy na wystawach w Paryżu (Lublin painters exhibited in Paris, „Ziemia Lubelska” 1928, no 349, p. 4) wrote: „(…) dr Julian Tur, Paris correspondent, informs that at the current Autumn salon at the Grand Palais in Paris, aside from Lewensztadt, also S. Trachter was remarkable”.

17 Widokówka do W. Ziółkowskiego z 3 marca 1928 r., Korespondencja WZ, k. 104.

18 M. Weinzieher, Symche Trachter…, dz. cyt.

19 Pejzaż Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Muzeum Lubelskie w Lublinie (dalej ML), nr inw. S/Mal/1421/ML, zob. katalog, Obrazy olejne, nr 7.

20 Pejzaż Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Muzeum Lubelskie w Lublinie (dalej ML), nr inw. S/Mal/1421/ML, zob. katalog, Obrazy olejne, nr 7. There also information about the painting by Eibisch.