- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

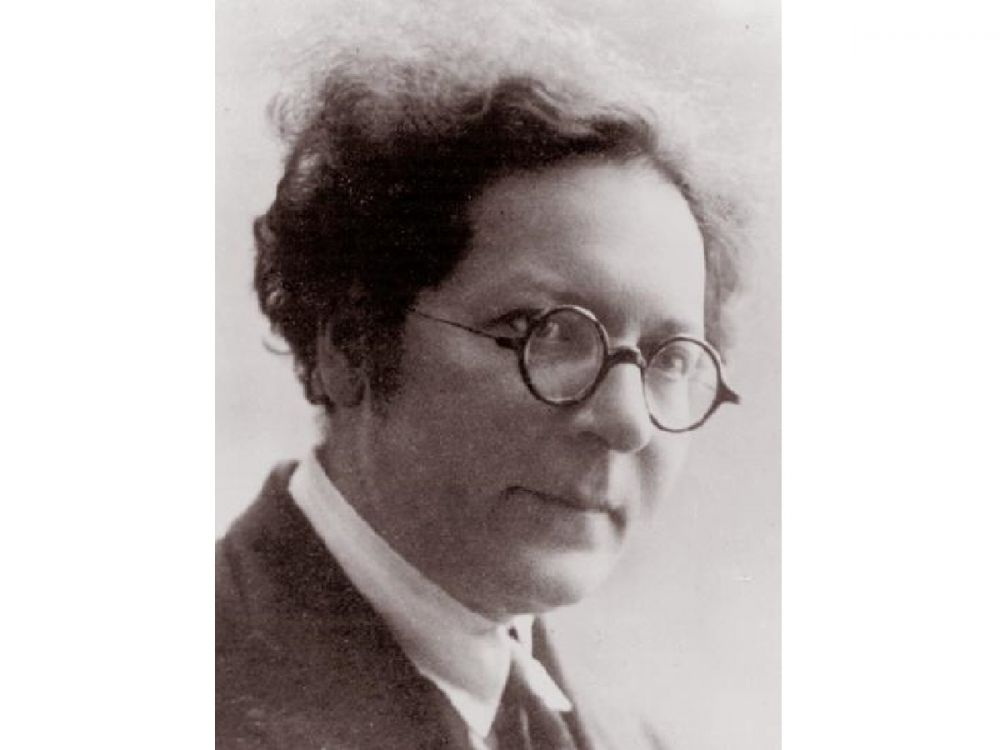

Alter Kacyzne /

Kacyzne's father was a bricklayer, his mother was a seamstress. They spoke Yiddish at home. He was learning at a cheder and Jewish-Russian general school, but he was also a keen autodidact — on his own, he learned to speak Hebrew, German, Polish and French.

When his father died in 1899, he took up an internship at his uncle’s photographic studio in Yekaterinoslav (currently Dnipro, Ukraine). At that time, he began to write short stories in Russian (he debuted in 1909) and poems which he was sending to Szymon An-ski.

He married Chana Chanow and in 1910, he moved with his wife to Warsaw where he opened his own photographic studio. He established contact with I.L. Perec who became his mentor in literature; afterwards, he became a contributor to many Jewish periodicals published in Poland such as „Literarisze Bleter”, „Bicher-welt”, „Ringen”, and between 1937–1939 he worked as an editor of „Majn redendiker film” (My Spoken Film). Soon, he became one of the most prominent personalities in the Jewish cultural life in Warsaw.

Kacyzne’s literary works initially dealt with the subjects of history and Romanticism, as in Der Gajst der mejłech (The ghost of the king, 1919), influenced by Juliusz Słowacki, and in theatrical plays — Der Dukus (Prince, 1926) and Hurdus (Herod, 1926). Later, he published a satirical and realist novel dedicated to contemporary themes — Sztarke und szwache (The strong and the weak, 1929). He edited and finished An-Ski’s drama Tog und nacht (Day and night). Together with Marek Arnstein, he wrote a script to the Dybuk movie, based on An-Ski’s drama. In terms of film scripts, he wrote also a screenplay to On a Hejm (The homeless, 1939, based on a stage drama by J. Gordin). In his poems from the Baładn un groteskn book (Ballads and grotesques, 1936), he revealed his fascination with folklore. In the 1930s, he became affiliated with the left, publishing many political articles and his own daily, „Frajnd” (1934–35).

Kacyzne was also an excellent photographer, documenting the life of the Jewish community in interwar Poland. In the 1920s, commisioned by HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) he made an extensive documentation of the life of Polish Jews, while for New York daily „Forwerts” („The Jewish Daily Forward”) he was contributing feature stories from Poland, but also Palestine, Spain, Morocco, Italy or Romania. Influenced by Szymon An-Ski and his ethnographic studies in Volhynia and Podole, he began to record the daily life of the Jewish community, initially in Warsaw and its immediate surroundings, later also in the Lublin region, Galicia, and the Eastern Borderlands.

Kacyzne focused on shtetls — the small town, where the Jewish communities, large and poor, were cultivating old traditions and folklore. He visited Biała Podlaska, Dęblin, Garwolin, Hrubieszów, Kazimierz Dolny, Łaskarzew, Łuków, Maciejowice, Międzyrzec Podlaski, Parysów, Ryki, Wąwolnica and others. Many of his images were dedicated to Lublin and its Jewish district of Podzamcze. Many photographs which have survived depict interiors of non-existent synagogues (Saul Wahl’s Synagogue), tenement houses, streets which are not there anymore (Szeroka, Krawiecka).

Kacyzne was also taking portraits of many renowned personalities, artists, politicians and jourmalists, who were frequently visiting the hospitable, always open Kacyzne house in Świder. One of such guests was Isaac Bashevis Singer.

When the war began, he moved to Lviv with his wife and daughter. He worked as a publisher and artistic director at the State Jewish Theatre opened in November 1939, managed (until Spring 1940) by Ida Kamińska who moved from Warsaw. He also contributed to „Czerwony Sztandar” (The Red Banner), expressing support for independent post-war Poland, which led to a conflict with Ukrainian writers. Polish writers recalled him in a positive light.

After the seizure of the city by the Germans, Kacyzne found himself in Tarnopol, where he was murdered in a pogrom on 7 July 1941.

Emanuel Ringelblum dedicated one of his notes from the bunker to him:

A well-known Jewish writer went to Lviv when the war broke out. During the Soviet rule, he was very creative, in a literary and social sense. When the Germans took power, he escaped to Tarnopol, where he was arrested and sent to forced labour. Kacyzne protested against mistreatment by the Ukrainian guards and expressed it. They punished him by torturing him to death. [1]

Kacyzne’s murder was witnessed by, among others, Nachman Blitz (Blic) (1906–1993), a poet who lived before the war in Lviv and Kazimierz Dolny. He described it in an article in „Dos Najes Lebn” (Newlife) published in Łódź in 1946.

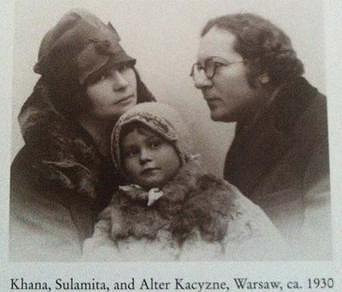

Kacyzne’s wife was killed in an extermination camp in Bełżec. Their daughter, Sulamita (Chaja) Kacyzne-Reale survived the war thanks to „Aryan papers”. After the war, she dedicated herself to discovering and organizing her father’s oeuvre. She died in 1999, at the age of 72.

Almost all photographs by Alter Kacyzne were destroyed during the war. Those which survive, about 700, are stored at the YIVO archives in New York — the 1920s and 1930s photographs for HIAS and for „The Jewish Daily Forward”. They were published in albums: The Vanished World, publ. R. Abramovitch (1947), Image Before My Eyes, ed. L. Dobroszycki i B. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1977), Poyln. Jewish Life in the Old Country, publi. and ed. by M. Web and F. Gottesfeld Heller (1999).

Sources:

Zofia Borzymińska, https://www.jhi.pl/psj/Kacyzne_Alter

http://teatrnn.pl/leksykon/artykuly/alter-kacyzne-1885–1941/

Footnotes:

[1] Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 29a, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, ed. Eleonora Bergman, Tadeusz Epsztein, Magdalena Siek, JHI Press, Warsaw 2018, p. 211.