- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

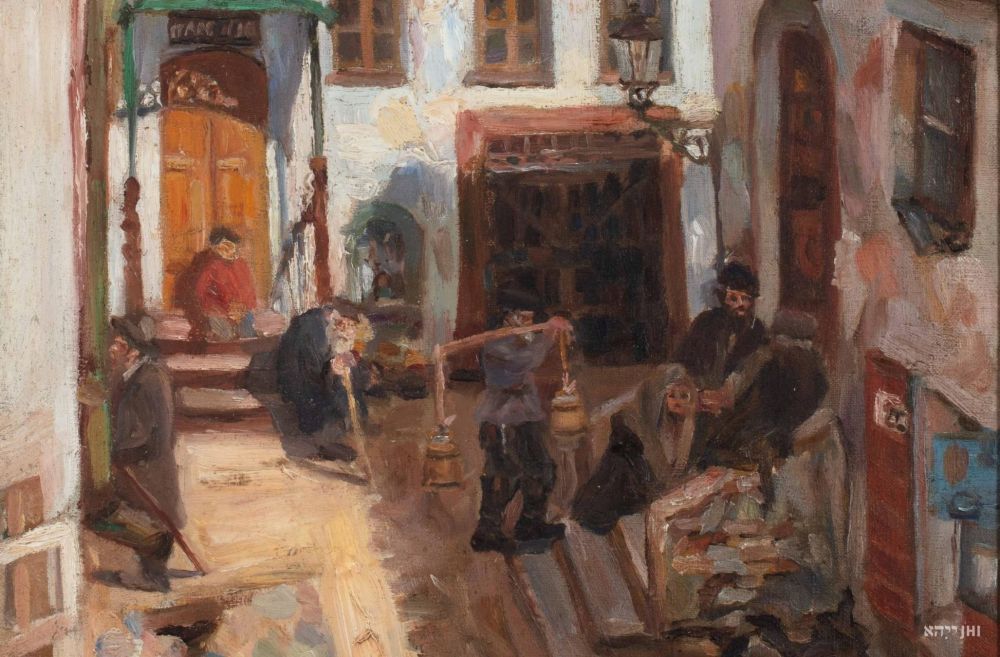

Rafael Lewin, Old synagogue in Vilnius, 1928, JHI collection (fragment)

The famed recluse

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (Eliahu ben Shlomo Zalman), the Gaon of Vilna, or Hagra, has been universally acclaimed as a pinnacle of Lithuanian Jewish scholarship. Israel Zinberg expressed exactly that traditional opinion writing that “as a scholar, the Gaon of Vilna undoubtedly created the most significant and valuable things which it was at all possible to create within the limits of the contemporary rabbinic world”[1]. The Gaon’s epitaph on his gravestone at the Vilna old Jewish cemetery (preserved in his current burial place) acclaims those great achievements even more eloquently:

The mysteries of the Bible, the Talmud, the Kabbalah and all the sacred books were clear to you,

as if you had received this all directly from our ancient sages [tannaim and amoraim].

…the unrivaled researcher of the Bible, the Mishnah, both Talmuds, all collections of religious law, the Kabbalah books [the actual names of the classical texts are mentioned], and creator of their corrected versions. Neither major, nor minor problems of the sacred texts did he ever left unsolved, until the texts became as if they had just been received on Mount Sinai. Having corrected numerous textual inaccuracies, he brought back the opportunity to perform the Torah commandments accurately, to the great joy of the people.[2]

![gaon_portret_zw_2.jpg [2.09 MB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/10/4/b10e0e06de9f1c88a1469e30ae16277a/jpg/jhi/preview/gaon_portret_zw_2.jpg)

The reader of the epitaph would also assume that the close ties between the great man and his surroundings were severed by his death:

Our great teacher, why have you left us like orphans!

who will expound the issues of the Scripture, who will comprehend the word of God, who will educate us on pious behavior?

For we are used to drawing from your insights and enjoying them every day.

(…) Both piety and study will be undermined – who will deliver them without you?

But it was hardly a truthful statement, because there were virtually no direct contacts between the Gaon Elijah and the community, and he didn’t “deliver” examples, be it in teaching or behavior, perceptible for many.

Famously reclusive, he never formally taught in a yeshiva or established his own, and studied with a small circle of devoted disciples. He was even not interested, during his lifetime, to spread his teaching through publications. Thus, he was very far from “daily” sharing his knowledge with masses. In Shaul Stampfer’s words, “to the degree that the Gaon addressed himself to anyone, it was to an elite, and his philosophy was definitely directed to an elite of the elite”.[3]

Symptomatically, among the numerous works in a variety of genres that were published after Gaon’s death there were no responsa, e.g. practical halachic (pertaining to religious law) guidelines to individuals and/or community, and as far as it is known, none were sent in his lifetime. Even popular legends, originated in the 19th century “biographies” of the Gaon, that, in Zwi Werblowski’s observation, are rather of hagiographic character[4], underline the rareness of occasions when one could actually have encountered him.

One of these legends mention the Gaon’s brilliant sermon in the Great Synagogue of Vilnius when he was only 3 years old (or 6, depending on a version of the legend). Another tells about a miraculous rescue of the community during the Polish Kościuszko uprising of 1794, when the Gaon’s recitation of a psalm in the same Great synagogue stopped a Russian cannonball from exploding. All that means, rather strikingly, that the Gaon was communally engaged only twice in his lifetime. It seems that in Gaon’s Vilnius everybody knew about him, but virtually nobody knew him.

![wilno_synagoga_1_zw.jpg [488.76 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/4/27/4c8483916006ac725c3fa572700fdf11/jpg/jhi/preview/wilno_synagoga_1_zw.jpg)

“The greatest sage of our land”

It is a well-known fact that the community supported the Gaon by means of a stipend, but how did they arrive at the conclusion that exactly he was such singularly bright a scholar that should be exempt from every work and community service and financially aided in his single pursuit, Torah study, remains a mystery. Maybe a partial explanation is that upon Elijah’s return to Vilnius after his short journey through Poland and Germany, his reputation as a young genius preceded him – for example, Jonathan Eibeschütz, having acquainted Elijah and corresponded with him, wrote of him in his Luchot edut [Tablets of Testimonies]: "extraordinary, holy and pure in nature and all-encompassing competency." (In 1756, when Eibeschütz published the book, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman was only 36). In any case, for most of his contemporaries the Vilna Gaon was as elusive a figure, as he was charismatic.

Of course, in a later period one could claim knowledge of the Gaon’s teaching drawn from his published works. These began appearing in 1799, some quite regularly: for instance, two commentaries to the Mishna: Shenot Eliyahu [Elijah’s Years] and Sefer Eliyahu raba [The Great Book of Elijah] that were always printed by the Romm’s Publishers in Vilnius alongside, respectfully, Zeraim and Taharot divisions of the Mishna. And, obviously, the celebrated Vilna Shas – the full edition of the Babylonian Talmud published by the Romms in 1860-1880, that included glossas by the Vilna Gaon, was a great source of his insights. Gaon’s works, carefully prepared by editors, many of whom were his sons and students, included also commentaries on his texts. It was really the best way to finally get in touch with an intellectual legacy of that revered sage.

Shaul Stampfer argues though that “apparently the Gaon was remembered but not studied”[5], “(…) respected much more than he was imitated. Precisely his brilliance made it unlikely that someone would try to follow in his footsteps”[6]. And on the issue of the Vilna Gaon as a role model in general, Stampfer summarizes: “It appears that the more the Gaon was regarded as sui generis, the more he was irrelevant as a model for behavior”.[7]

Nevertheless, even in popular imagination, the Gaon’s expertise was unsurpassed – as renowned Vilnius librarian and kulturtreger Chaikl Lunski has written in his 1920 article, „by a single short note he overthrew a whole mountain of barren sophistication [pilpul]“.[8] But the scope of that expertise was really known to few, and even the person who knew him well, his devote disciple Chaim ben Isaac from Volozhin, resorted to generalizing epical rhetoric in his account of the fields in which the Gaon expressed himself: “[He was] a true expert in the Bible, Mishna, both Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds, Mechilta, Sifra and Sifre, Tosefta, midrash [aggadah] and Zohar, and augmented all the known works of the tannaim and amoraim, and also wrote many additional halachot, aggadot and midrashim, and things that constitute mystery of mysteries”.[9] It seems that the anonymous author of the Gaon’s epitaph could well be Chaim ben Isaac (also called Chaim of Volozhin) himself, so close the choice of phrase and sequence of the Gaon’s achievements is to the rhetoric of the eulogy. All in all, from diverse sources we have a description of an intellectual giant, a paragon of Torah learning, or, as Louis Ginzberg formulated in his famous article of 1928, “the Gaon par excellence”[10].

Chaim of Volozhin was famous for establishing the yeshiva that he hoped to base on the Gaon’s method of Torah study and to educate young talmide chachamim (Torah scholars) in the intellectual and moral spirit of the Gaon. In his appeal to future students, teachers and donors in 1802 rabbi Chaim uses the name and reputation of the Gaon as a guarantee of high aspirations and noble goals:

I must bring to mind the name of the pious Vilna Gaon Elijah, the greatest sage of our land, and to rejoice that I can call myself his disciple, but at the same time I do not wish to hide behind his glory; for no one can compare to him in all the dimensions of the Torah study (…) while I myself was unable to learn the smallest fragment of his wisdom. (…) Thus, it is understandable that I appeal not to the wisest for I have no right whatsoever to do so, but to our young brethren who have not yet had a chance to experience the true sweetness and profoundness of the Torah: let them come to me, I might succeed somewhat in directing them to that path, in providing them with the taste of the Torah. So, come also those like myself and those wiser than me, to teach the young... [11]

As one can see, the use of the Gaon’s name here is rather emblematic, it functions, in a way, as a seal on the letter, giving it more weight. Indeed, famous and successful as it was, the Volozhin yeshiva became renowned through its talented scholars who were great thinkers themselves and not necessarily immediate spiritual heirs of the Vilna Gaon.

Gaon in every Jewish home

During the 19th and 20th centuries, when a cluster of “Lithuanian yeshivas” was formed in the territory of nowadays Belarus and ethnographic Lithuania, every one of them developed its specific agenda and mode of study. Virtually in no memoir the legacy of the Vilna Gaon is mentioned either as study material or in any symbolic way: the figures of the particular gaonim – the heads of the yeshivas were much more significant. Nevertheless, we can assume that in the beginning of the yeshiva movement his image contained a potent appeal and brought part of the success to the campaign of rabbi Chaim of Volozhin.

The Gaon’s image was formed as early as his death and preserved in time without much change as an essential part of Vilna Jewish “hall of fame”. The writer Zalman Shneur, who stayed in Vilnius in 1904-1906 and anthologized his impressions of the city in his poem Vilna (written in 1917 and published in 1919) gave a vivid testimony of just how popular the visage of the Gaon was to Vilna Jews: “А portrait of the Vilna Gaon benevolently welcomes guests in every Jewish home”.

Through the later years this image had been cemented in communal consciousness to the extent that the Gaon Elijah became kind of a patron of the Vilna Jews, without direct correlation to their proficiency in classical Jewish texts or even their religiosity. As Justin Cammy put it, in an interwar period a Vilna Jew had “a sense of civic pride and ownership over a traditional past in which the Gaon could be claimed as a folk hero even by secular Jews”.[12]

This was demonstrated in 1920, when Vilna celebrated the Gaon‘s 200th birth anniversary. Although, as David Fishman points out[13], it was mostly commemorated by the religious segment of the community in a traditional way of services and public sermons, secular press also covered the events. Paradoxically enough, one of such publications, the lengthy article by Joseph Aba Trivosh in non-religious Vilnius Hebrew monthly He-chaim [The Life][14], actually criticizes secular forms of the celebration as not being authentic “to the ways of the Gaon himself”. On the other hand, Trivosh’s essay is clearly oriented on making the Gaon relevant to modernist and rationalist contemporary consciousness. He depicts the sage in a very maskilic manner (notably, Trivosh himself was a historian and popularizer of Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment; maskils were Haskalah supporters) as an expert in sciences and a person of broad horizons to which image, in Trivosh’s thought, a modern Jew could relate.

The commemorating of the Gaon’s 200th birth anniversary was also the first attempt to incorporate the Gaon into general, not only Jewish, Vilnius cityscape. The Jewish community proposed to the municipality to rename one of the streets near the shulhoyf, the synagogue’s courtyard, after the Gaon, and this was indeed implemented, although not without hesitation from a part of the city council.[15]

Secular publications sporadically mentioned the Gaon later on, although the number of materials was much bigger in the orthodox press, mainly in the weekly Dos Vort [The Word] that in 1934 presented a series of articles on the Gaon and in 1935 – on his disciples. The author of both series was aforementioned Chaikl Lunski who himself, by the way, was not strictly orthodox and actively worked in secular cultural environment. It was Lunsky who recognized a modern educational value in the Vilna Gaon’s image and published a small book of legends about him for schoolchildren in 1924.

This corresponded to the interwar boom of Jewish folkloristic that in Vilnius was embodied first by the Jewish historical-ethnographic society, and from 1925 – by the YIVO institute and its Ethnography Committee. Active members of both organizations were Lunski and the pedagogue and folklorist Solomon Bastomski, who regularly published folklore anthologies in his series Di naye yidishe shul [The New Jewish School]. Both Lunski and Bastomski regarded figures of Jewish past, among them the Vilna Gaon, as emblems of national identity fitting as examples in strengthening that identity in the young. Interwar Jewish folklorists also keenly felt their mission in preserving the memory of traditional Jewish world, represented by folk art and lore. In 1939, Bastomski published a collection of legends of Ger Tzedek [“true convert” to Judaism], the semi-legendary proselyte figure closely connected to the Vilna Gaon, in the Vilner almanac [Vilna Almanac] – the last prewar collection of texts and photographs dedicated to the city’s Jewish past and present.

Before the end of Jewish Vilna

All that doesn’t mean that in Vilnius there were no attempts of serious study of the Gaon’s legacy and his impact on the Jewish thought.

The Gaon was included in the Vilna Jewish historiography tradition beginning from its formative text – Kiriya neemana [The Faithful City] published by Samuel Josef Finn in 1860. Finn’s work was continued by his aid Hilel Noach Magid-Steinshneider in the latter’s monograph Ir Vilna [The City of Vilnius] of 1900. In 1935, a Jewish author with an academic training – a master degree from the Vilnius University, Israel Klausner, a future famous historian, published a small Hebrew monograph The History of the Old Jewish Cemetery to which he added a plan of the Shnipishok cemetery where the Vilna Gaon was buried. In 1938, he published the larger book The History of the Vilna Jewish Community. (Although he left for Palestine in 1936, the second monograph was published by the Vilna Jewish community, in two versions: the original Hebrew and in translation to Yiddish). In both books the Gaon holds a prominent part; and in 1942 Klausner published in Jerusalem a continuation of his research with even more focus on the Gaon, as the name of the monograph, Vilna in the Time of the Gaon, suggests.

Of course, in wartime Vilnius the perpetuation of the Gaon’s name was not possible – or so it may seem. In reality, there are at least two instances of his direct or indirect commemoration in the Vilna ghetto. First is the description of Vilnius Jewish cemeteries made on request of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg – a German unit tasked with looting works of art, libraries and archives – with addition of about 200 epitaphs. It is a typescript in German penned by Obereinsatzführer Wilhelm Schäffer in which he mentions “the aid of the locals”.[16] Last year, the original manuscript register of the epitaphs from Shnipishok cemetery was found in the National Library of Lithuania. It is written in different hands; the epitaph of the Gaon Elijah is copied by Chaikl Lunski, the pre-war champion of the Gaon’s fame.

The second instance of the Vilna ghetto connection to the name of the Gaon is the fate of the pinkas (minute-book) of the Gaon’s kloiz, or synagogue, that was a part of the Vilna shulhoyf and in itself constituted a homage to the Gaon. During the Nazi-ordered sorting of the plundered Jewish documents in the ghetto, the poet Avrom Sutzkever hid the pinkas that before the war belonged to the archival collection of the YIVO Institute, and after the liberation of Vilnius was able to retrieve it. Upon leaving Vilnius in 1947, he smuggled it and returned to the new YIVO headquarters in New York. The story of the rescue is laconically inscribed by him on the blank page of the pinkas, and in detail described by David Fishman[17].

Again, only last year another part of that puzzle, namely, the way of the pinkas to the Vilnius YIVO, was disclosed due to locating in the National Library of Lithuania of a letter written in 1940, under the Soviet rule, by then director of the YIVO Noach Prilutski to one David Rosenblum. Prilutski thanks him for donating the pinkas to the archives of the Institute, but requires to provide an explanation about how did he come into possession of it. No answer by Rosenblum has yet been found, but it seems that, although not being a member of the personnel of the Gaon’s kloiz, he witnessed the activities of Soviet administration in the synagogues, which inevitably included looting (as a form of “nationalization”), and saved the document. It is worth mentioning that the last publication of the Vilna Gaon’s book in Lithuania took place in Kedainiai in 1940, on the eve of the Soviet occupation that ended the development of Hebrew culture and effectively closed Jewish religious life in the country.

Almost full annihilation of Lithuanian Jewish community by the Nazis from 1941 to 1944 and antireligious policies of the Soviets who again ruled Lithuania from 1944, left Vilnius with a very small Jewish community, one acting synagogue and one acting cemetery. There was almost nothing the community could do due to the control of the communist party, so they could not protest the decision of Vilnius administration to level down historical Jewish cemeteries and use the gravestones as building material. In the 1950s, when the Shnipishok cemetery was being destroyed, they asked the permission to transfer the remains of the Vilna Gaon and his family, as well as a few other prominent Jews, to the acting cemetery.[18] The Gaon’s name, or rather, the reverence with which it was treated, made an impression on the authorities, and the permission was given. (A small success was achieved in the 1960s, when a similar grave relocation was allowed at another Jewish cemetery, at Uzhupis, that was then destroyed as well).

In 1944 the Jewish museum was established in Vilnius. Its staff frantically searched the ghetto territory and the whole city for Jewish documents and artefacts – those that were hidden during the Nazi occupation, and those that were just scattered through the city without owners. After all the looting and ruining they still gathered an impressive number of cultural treasures, the surviving books of the Vilna Gaon, many Talmuds and parts of the library of the Gaon’s kloiz among them.

However, in Lithuania, as in the whole Soviet Union, the regime implemented unofficial, but very obvious anti-Semitic policies. In 1949 the Jewish Museum was closed, and its exhibits dispersed among different cultural institutions. The institution called the State Book Chamber, whose head from 1946 was Antanas Ulpis, received most of the books and documents collected by the Jewish museum. Even before the transfer Ulpis and other dedicated members of the staff of the Book Chamber became so concerned about the fate of abandoned books, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, that they organized gatherings in Vilnius, as well as numerous expeditions into Lithuanian province, with the task to rescue what was possible. The biggest part of their findings constituted Jewish materials, because the Jewish population of provincial towns and rural places was almost non-existent.

On Ulpis’s instructions, the Book Chamber also acquired printed materials from antiquarians, private owners etc., and among those acquisitions, there were also Judaica. As a result, after the 1949 closing of the Jewish Museum more than 50,000 books, hundreds of full or fragmented periodicals sets and close to 200 boxes of documents were gathered at the Book Chamber and concealed from further destruction by the Soviets in the huge labyrinthine building of former St. George Church that was assigned to the Book Chamber, where they stayed for decades. Only at the end of the 1980s a small group of people with knowledge of Jewish languages acquired in a course of pre-war Jewish education was officially invited by the next director of the Book Chamber, Vladas Lukošiunas, for processing of the books and periodicals. Later the Book Chamber was integrated into the National Library of Lithuania.

The Gaon’s comeback

The work of the group was led by Esther Bramson. When in 1995, on her invitation, I joined the work, I was proudly informed about one book of the Vilna Gaon that the National Library possessed. This inaccurate information was based, first, on the fact that the books were still being processed, and second, on the circumstance that due to the lack of human resources the group had no time to analyze editions of Talmud, Mishna and other classical texts by their commentators and so was unaware of the Gaon’s commentaries in these publications.

However, already in 1997, when the massive commemoration of the 200th yortsayt, or death anniversary, of the Vilna Gaon happened in independent Vilnius, the Library was able to present to a large international audience the exhibition of about 50 works of the Vilna Gaon called “The Precious Legacy”. This celebration, that included also an international scholarly conference, several publications, proper burial of damaged Torah scrolls and return of the Gaon’s name to the street that had it in the interwar period, was a beginning of the Vilna Gaon’s comeback to his city.

Since then, those who seek better knowledge of the Vilna Gaon gained access to local and world archives and academic literature, international academic exchange and opportunities to involve in Jewish studies. And although, even after the celebrations and the veritable avalanche of information that reached the Lithuanian society in 2020, when the Lithuanian government decided to celebrate the year of the 300th birth anniversary of the Vilna Gaon, we cannot pretend to know him really well, at least he once again became a household name in Vilnius, and this time not only for its Jewish community.

_____

The exhibition is financed by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway from the EEA Grants and the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage

![granty_norw_EN.jpg [39.66 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/1/b5c2e62f4995b8a22f0d0e59a1673d2a/jpg/jhi/preview/norweskie_EN_do_2021.jpg)

_____

Footnotes:

[1] Zinberg, Israel. A History of Jewish Literature, I-XII. Cincinnati-New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1972-1978. V. VI: The German-Polish Cultural Center, p. 229

[2] Quoted from: Finn, Samuel Joseph. Kiriya Neemana [The Faithful City]. Vilnius: Romm Publishing, 1860, p. 146. Hereafter translations from Hebrew and Yiddish by the author of the article.

[3] Stampfer, Shaul. “The Gaon, Yeshivot, the Printing Press and the Jewish Community – a Complicated Relationship”, in Lempertas I., ed. The Gaon of Vilnius and the Annals of Jewish Culture. Vilnius: Vilnius University Publishing, 1998, p. 265-266

[4] Werblowski, Zwi. “The Mystical Life of the Gaon Elijah of Vilna”, in idem, Joseph Karo – Lawyer and Mystic. London: Oxford University Press, 1962, app. F, p. 308

[5] Stampfer, The Gaon, p. 258

[6] Ibid., p. 262

[7] Ibid., p. 263

[8] Lunski, Chaikl. „Some Thoughts on the Vilna Gaon‘s 200th Birth Anniversary“ [Yid.], Lebn ,Vilnius, 1920, nr. 2, p. 32

[9] Letter of R. Chaim of Volozhin [Heb.], Ha-peles, II. Poltava, 1902, p. 142

[10] Ginzberg, Louis. “The Gaon, Rabbi Elijah Wilna”, in idem, Students, Scholars and Saints. New York: Jewish Publicatiom Society in Amerika, 1928, p. 125

[11] Letter of R. Chaim, p. 142

[12] Cammy, Justin. "“The Poetry of Landkentenish: Litvish Landscapes and Vilna Peoplescapes,”, presentation at the conference Reading Vilna in Jewish Writing and Urban History, Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore and Vilnius University. Vilnius, August 2019

[13] Fishman, David E. “Commemorating and Conflict: the Observance of the Vilna Gaon’s 200th Birthday”, in Lempertas I., ed. The Gaon of Vilnius and the Annals of Jewish Culture. Vilnius: Vilnius University Publishing, 1998, p. 179-186

[14] Trivosh, Joseph Aba. „The Gaon of Vilna (on his 200th Birth Anniversary)“ [Heb.], He-chaim, Vilnius, 1920, nr. 1, p. 4-6; nr. 2, p. 7-8; nr. 3, p. 3-5

[15] Fishman, Commemorating and Conflict, p. 181-182

[16] Lithuanian Central State Archives, F. R-1421, ap. 1, b. 494

[17] Fishman, David E. The Book Smugglers. Partisans, Poets and the Race to Save Jewish Treasures from the Nazis. New York: ForeEdge, 2017, p. 52-54

[18] Lithuanian Special Archives, F. 1771, ap. 11, b. 274