- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Szlama Ber Winer was born in 1911 in Izbica Kujawska, from where he was transported by the Germans to Chełmno on 5 January 1942. There, in a village called by the Germans Kulmhof an der Nehr, and in Las Rzuchowski several kilometres away, the first stationary location of extermination of Jews was established. The extermination camp was functioning from 7 December 1941 until 7 April 1943, and between June and July 1944. The number of victims of the Chełmno camp remains unknown – it is estimated that about 200,000 people had been killed there, mostly Jews, but also Poles, Romani, and Soviet prisoners. [1]

In Chełmno, people had been murdered on a mass scale using car exhaust fumes. Prisoners who arrived at the camp were told to take their clothes off and rushed to cars, from which they could not escape. The cars with prisoners were driven onto a forest glade in Las Rzuchowski. The exhaust pipes were redirected inside the cars so that within 15–20 minutes, they would cause death of asphyxiation. Szlama Ber Winer’s loved ones had lost their lives this way. In his account, written down after his arrival to the Warsaw Ghetto, he recalled:

During lunch, I’ve received the sad news: my dear parents and my brother were in their graves. At one o’clock, we were back at work. I was trying to move closer to the dead ones, to see my loved ones for the last time. I was hit with a frozen lump of soil by the good-natured German with a pipe, and the „Whip man” fired a shot at me. I’m not sure if he wanted to miss, or if it was by accident, but I survived. Ignoring the pain, I was working very fast in order to forget about my horrible loss even for a while. I was left alone in this world now. Out of my family of about 60 people, I was the only remaining survivor. [2]

Szlama had a chance to escape because in Chełmno, he was assigned to the forest commando (Waldkommando), whose responsibility was to buried the bodies of the murdered Jews. They were held in the basement of the former palace, and even after several days of digging graves, they became aware that they’d be killed as well, and that escape was the only chance for survival. On 19 January 1942, Szlama ran away – during transport, he managed to escape through a small window of a truck. As he wrote later, his goals, aside from rescuing his own life, was to let the world know about what was happening in Chełmno. Through all that time, I was calling to God and my parents to help me save the Jewish nation. [3]

The same day, he found shelter at the rabbi’s house in Grabów: The servant (the rabbi is a widower), with eyes puffy from crying, brought me a bowl of water. I began to wash my hands. A wound on my right hand began to hurt. When the news spread in the city, many Jews came to the rabbi, and I told them in detail about the horrible events. Everyone was crying. I ate bread with butter, I drank tea, and I said the thanksgiving prayer. [4]

After a long journey, he managed to reach the Warsaw Ghetto, where he received help from Hersz Wasser (secretary of Oneg Shabbat and employee of the Central Refugee Commission) and his wife Bluma, who in February 1942 wrote down Szlama’s detailed report about the mass extermination in gas vans in Chełmno. In the documents, Szlamek appears under a false name, Jakub Grojnowski.

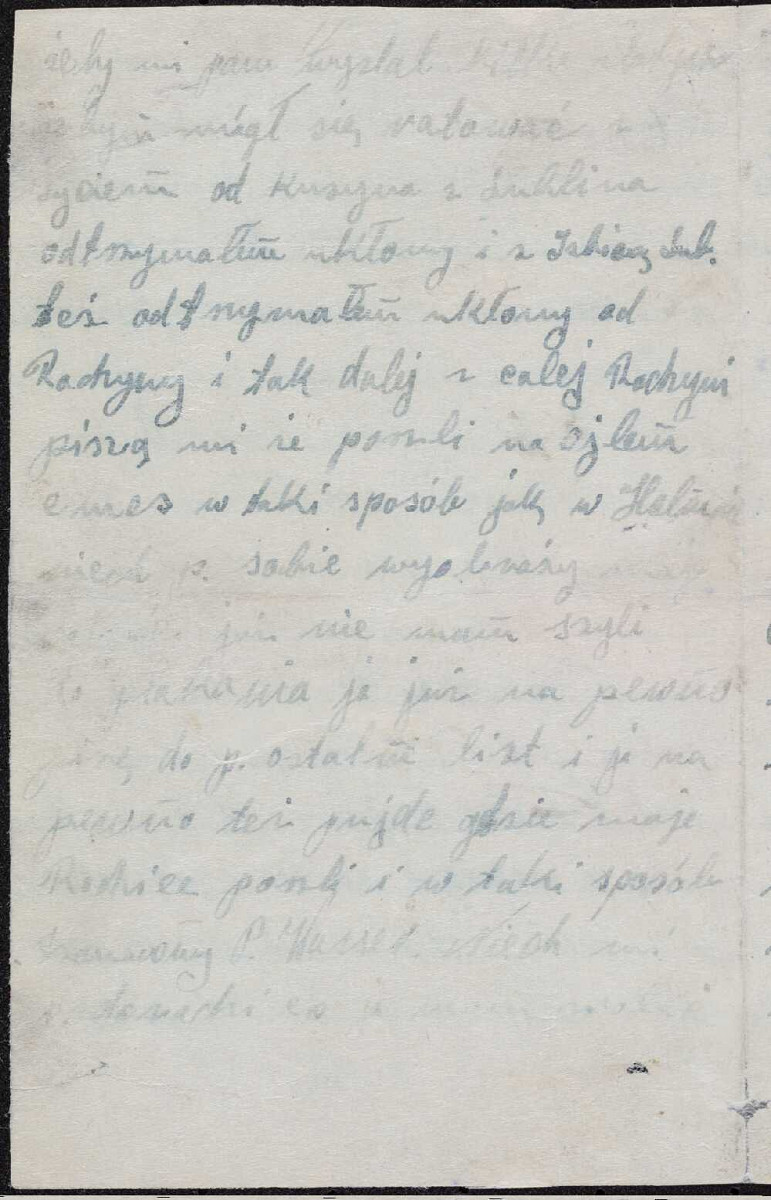

Fearing the police, Oneg Shabbat sent him to Zamość, to his relative Fela Bajlerowa. In early April, he was writing do Hersz Wasser in indirect words that in the Lublin region, the same things as he witnessed in Chełmno were taking place:

I have received greetings from a cousin from Lublin, and from my family in Izbica Lubelska as well. They wrote that the entire family have found themselves at the cemetery, in the same way as in Chełmno. Please imagine my despair, I have ran out of tears. This is prrobably the last letter I’m writing to you. I will probably join my Parents, in the same way. (…) The cemetery is located in Bełżec. It is the same death as in Chełmno. [5]

After the liquidation of the Zamość Ghetto on 11th or 12th April, he was transported to the Bełżec extermination camp. On 24 April Abram Bajler, Szlamek’s nephew, sent a letter to Bluma and Hersz Wasser, informing about the deaths of his mother and uncle Szlamek. [6]

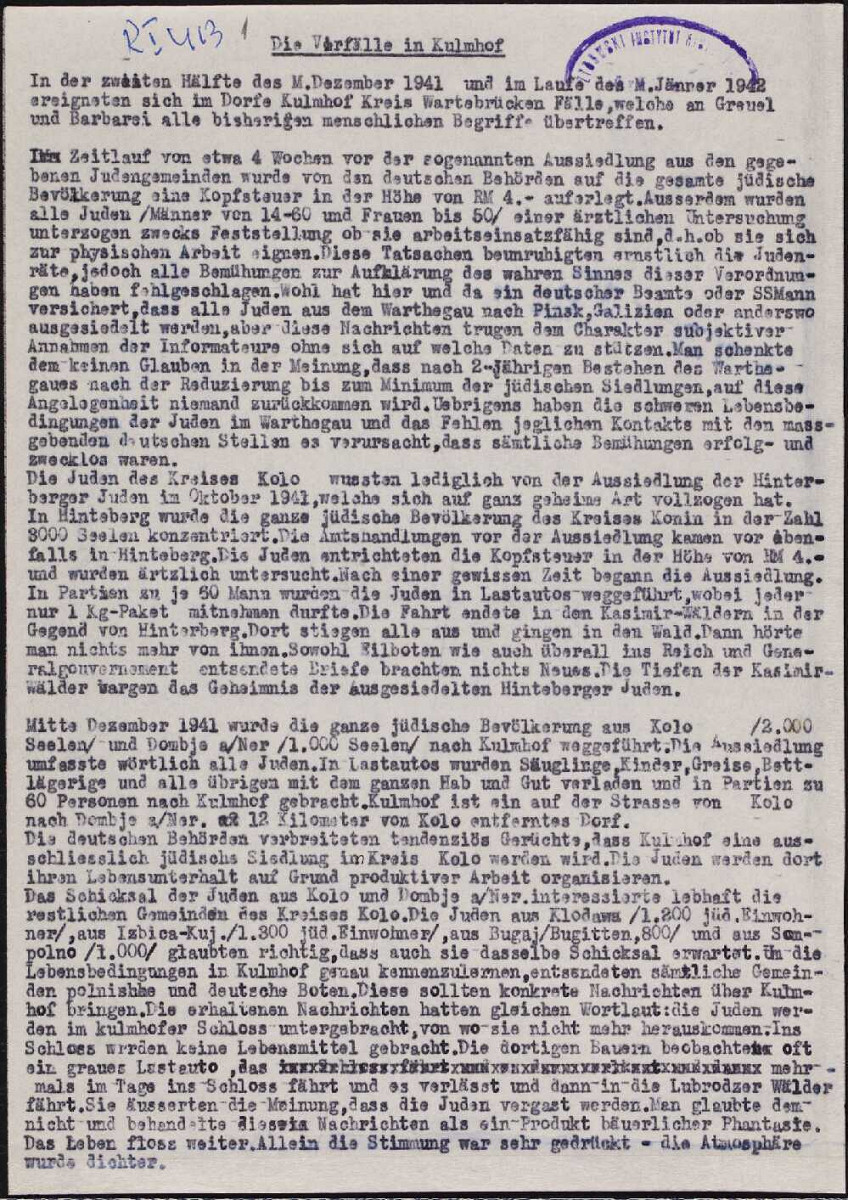

Basing on Szlama Ber Winer’s testimony (and other sources, such as Uszer Taube’s testimony), the Oneg Shabbat group wrote a report „The events in Chełmno” (25 March 1942), which informed about the mass extermination of Jews. The report was passed to the Home Army in March.

As Maria Ferenc Piotrowska and Franciszek Zakrzewski emphasised in their introduction to the 22th volume of the complete edition of the Ringelblum Archive – The press in the Warsaw Ghetto: news from the radio monitoring, information about the extermination camp in Chełmno had reached London in early June 1942 through a letter sent by the Bund leadership (11 May 1942) and delivered by Sven Norrman, a representative of a Swedish company in Warsaw. Some of the information was sourced by Bund from Oneg Shabbat’s „The events in Chełmno” report – in this sense, Ringelblum’s group was the primary source of part of the information delivered by Bund to London in May. [8]

Szlama Ber Winer’s testimony and Oneg Shabbat’s „The events in Chełmno” report were hidden in the first part of the Ringelblum Archive and discovered on 18 September 1946.

Footnotes:

[1] Przemysław Nowicki, Obóz zagłady w Chełmnie nad Nerem, https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/c/469-chelmno-nad-nerem/116-miejsca-martyrologii/139763-oboz-z....

[2] Pełna edycja Archiwum Ringelbluma, tom 23, Ostatnim etapem przesiedlenia jest śmierć, opr. Ewa Wiatr, Barbara Engelking, Alina Skibińska, s. 107.

[3] Ibidem, s. 110.

[4] Ibidem, s.111.

[5] Pełna edycja Archiwum Ringelbluma, tom 1, Listy o Zagładzie, opr. Ruta Sakowska, s. 130–131.

[6] Ibidem, s. 134.

[7] Ibidem, s 113.

[8] Maria Ferenc Piotrowska, Franciszek Zakrzewski, Wstęp do: Pełna edycja Archiwum Ringelbluma, t. 22, Prasa z getta warszawskiego: wiadomości z nasłuchu radiowego, s. XXXVIII.

The publication is a part of the Oneg Szabat Program, established by the Jewish Historical Institute and the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland. The aim of the Program is to share and to popularize the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto (the Ringelblum Archive) and to commemorate the members of the Oneg Shabbat group.