- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

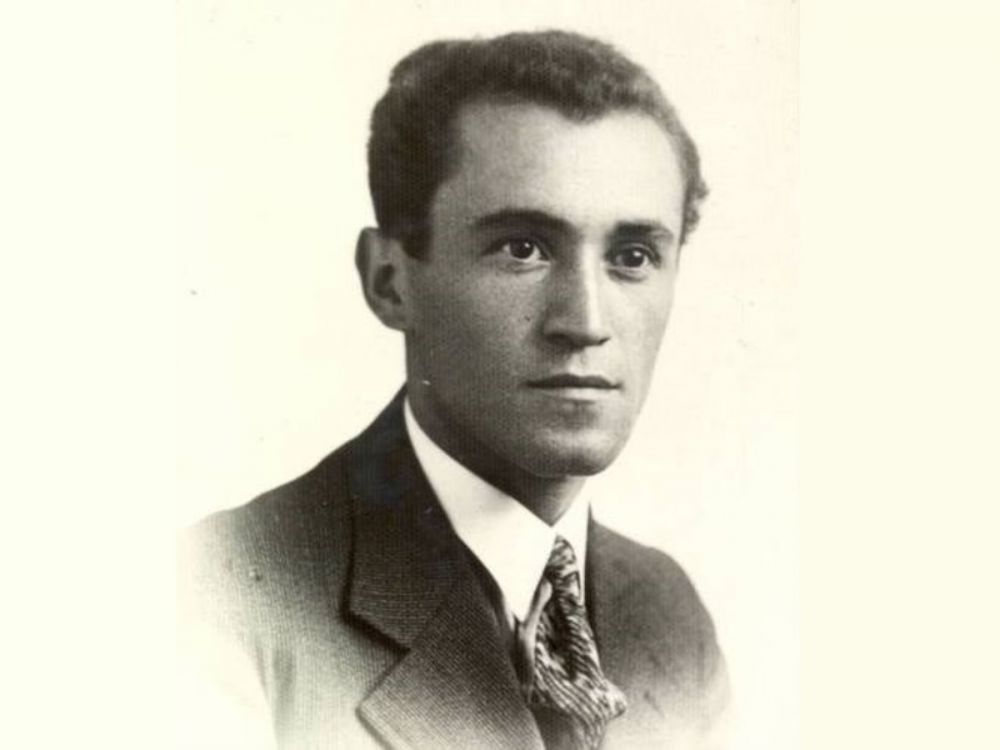

Artur Eisenbach

Artur (Aron) Eisenbach was born on April 7, 1906 in Nowy Sącz [1], in a religious Jewish middle-class family – his father traded in flour. He studied in Vilnius, Krakow and Warsaw. At the University of Warsaw, he studied under Professor Marceli Handelsman and Professor Majer Bałaban. He collaborated with the YIVO Institute (i.e. the Jewish Research Institute in Vilnius) and was active in the Young Historians' Club (Junger Historiker Krajz). In these institutions and groups he collaborated with Jewish historians: Ignacy Schiper, Rafał Mahler, and Emanuel Ringelblum. Also, he prepared a doctorate on the history of Polish Jews at the beginning of the 19th century. As Mahler and Ringelblum, he came from southern Poland, the former Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia, and belonged to the Poale Zion-Left party (Eisenbach joined the party at the age of 14).

"This group was united by the conviction that the history of the Jews should speak about the entire Jewish people, and not only about the intellectual and learned elite, and that former Jewish scholars did not appreciate the importance of class conflicts within the Jewish community" [2] – wrote Professor Antony Polonsky. Unlike Schiper and Mahler, however, Eisenbach tried to combine a Marxist-inspired approach in research on the history of Jews with the awareness of the influence of "spiritual tendencies" [3].

In 1931 Eisenbach married Giza Ringelblum, Emanuel's sister, in 1938 their daughter was born.

![eisenbach_cbj_1.jpg [176.85 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/4/6/39a69bd3fbdb0269721b14e93d1342b2/jpg/jhi/preview/eisenbach_cbj_1.jpg)

In September 1939, together with his wife and daughter, Eisenbach managed to get to Buczacz, the hometown of the Ringelblum family, which was under Soviet occupation.

"I will never forget the long and last conversation with him" – wrote Eisenbach about his meeting with Emanuel Ringelblum after the outbreak of the war – "carried out on the night of September 6-7, 1939, when after leaving our apartment in Żoliborz [district of Warsaw] (in the 7th colony of Warsaw Housing Cooperative, 3 Suzina Street), I arrived with my wife (Emanuel's sister) and our daughter at his apartment at 18 Leszno Street. I informed Emanuel that I would be leaving Warsaw in 2-3 hours and that his younger brother Leon had joined us. My arguments, as well as those of our friends, had no effect. Ringelblum was already determined to stay in Warsaw and, on behalf of «Joint», to take over the leadership of the social self-help action”[4].

When Germany attacked the Soviet Union, Eisenbach – then working as an accountant – was mobilized into the Red Army. In 1946 he returned to Poland. His wife and daughter probably died in the fall of 1942 in the Buczacz ghetto.

After the war, Eisenbach worked at the Łódź unit of the Central Jewish Historical Commission. He also became the head of the Archives of the Jewish Historical Institute and a professor at the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In 1966, after the death of Bernard Mark, he became the director of the JHI. In his research, Eisenbach focused in particular on the history of Polish Jews in the 19th century and the history of the Holocaust.

When the communist authorities launched an anti-Semitic campaign in March 1968, trying to suppress and cover pro-democratic student protests, the Institute was threatened with liquidation and the division of its collections. Eisenbach then resigned as director. “The year 1968 and its well-known events came as a deep shock to me. I have gone through some truly tragic moments. The whole structure that we had been creating with such effort for over a quarter of a century has collapsed. A situation arose that forced me to leave the Jewish Historical Institute, where I worked for 22 years” [5] – he recalled. However, he still published in the "Biuletyn ŻIH" [JHI Bulletin] and "Bleter far Geszichte" and even after retirement continued scientific work. In 1983 he published Emanuel Ringelblum’s Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto in Polish, and in 1986 Ringelblum’s essay Polish-Jewish Relations during the Second World War. He was also a consultant in the production of the film Austeria directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz based on the novel by Julian Stryjkowski [6].

In 1987, Artur Eisenbach emigrated to Israel. Suffering from cancer, struggling with traumatic memories of the war, lonely after the death of his second wife Maria Czarniewicz, he committed suicide in 1992. After his death, his photos, notes and other materials were placed in the Archives of the Jewish Historical Institute.

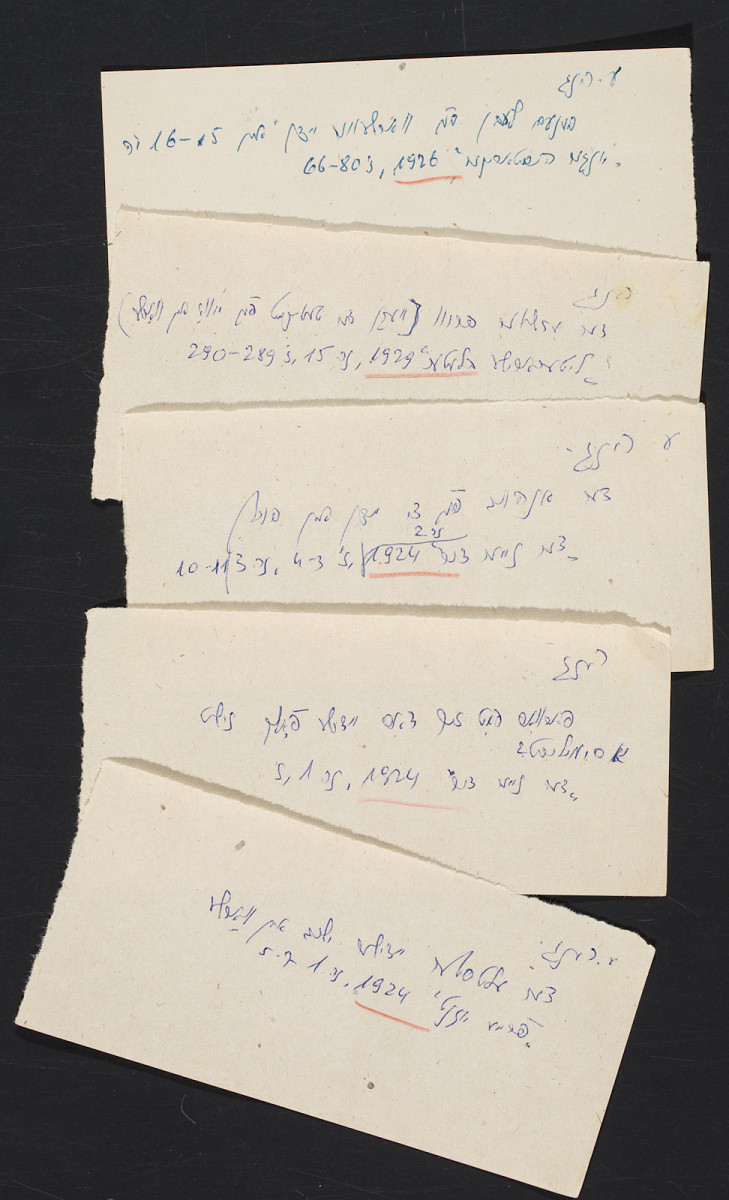

Artur Eisenbach's materials in the Archives of the Jewish Historical Institute "contain primarily notes to his post-war works, extracts from sources, drafts of articles and book chapters," – writes Aleksandra Bańkowska. – “Very difficult to read, but they give an interesting picture of the historian's workshop. While preparing many publications about Emanuel Ringelblum, Eisenbach prepared his scientific bibliography and made copies of student documents from the Archives of the University of Warsaw. In turn, when writing about the extermination of the Jewish intelligentsia, he wrote down all available information about outstanding figures of Jewish life who were imprisoned in various ghettos. Many of Eisenbach's notes come from the period when documents from the Łódź ghetto were prepared” [7].

“Eisenbach's legacy also includes his personal documents, state decorations, private and official correspondence (e.g. letters exchanged with the Czytelnik [Reader] publishing house regarding censorship of the text of the introduction to the second edition of Ringelblum's Polish-Jewish Relations). Surprisingly, there is a large collection of private photos, the oldest of which come from 1918. Unfortunately, they have no descriptions, we cannot recognize the people on the photographs". The boy on the rocking horse, however, appears similar to the adult Eisenbach.

Eisenbach's materials are a testimony to the rich work of a historian in three different research environments – emphasizes Bańkowska. During his work at Junger Historiker Krajz and the Warsaw section of YIVO, “Eisenbach was particularly interested in the legal situation of Jews during the Duchy of Warsaw period. He devoted several articles to this issue and his master's thesis defended in 1935 at the University of Warsaw as part of the seminar of Professor Marceli Handelsman".

After returning from the USSR to Poland, Eisenbach undertook research on the history of the Łódź ghetto. In the second half of the 1940s, he also acted as a court expert in several trials of German war criminals – Hans Biebow, head of the German administration of the Łódź ghetto (1947), Erich Czarnulla and Franz Siefert, criminals active in the Łódź ghetto (1947), Josef Bühler, participant of the Wannsee conference, convicted of crimes against the Polish nation in the General Government (1948), Jürgen Stroop and Franz Konrad, commanders of German forces during the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (1951), as well as in the trial of Michał Weichert, a theater scientist accused of collaborating with the Germans, who during the war belonged to the Jewish Social Self-Help, and then the Jüdische Unterstützungsstelle, a German-established service supplying, among other places, the Plaszow concentration camp.

“Until the end of the 1960s, the Holocaust was the main subject of Eisenbach’s research. He collaborated with Adam Rutkowski and Tatiana Berenstein, together they published a large collection of documents Eksterminacja Żydów na ziemiach polskich [The Extermination of Jews in Poland] and Emanuel Ringelblum's chronicle from the Warsaw Ghetto in Yiddish. However, Eisenbach's greatest achievement was the synthesis of the history of the Holocaust – Hitlerowska polityka eksterminacji Żydów w latach 1939-1945 jako jeden z przejawów imperializmu niemieckiego [Hitler's policy of extermination of Jews in 1939-1945 as one of the manifestations of German imperialism], which appeared in 1953 ”.

At the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences Eisenbach “dealt with research on Jewish society in the 18th and 19th centuries. The fruit of this work were the books: Kwestia równouprawnienia Żydów w Królestwie Polskim [The Question of Equal Rights for Jews in the Kingdom of Poland] (1972), Wielka Emigracja wobec kwestii żydowskiej [The Great Emigration and the Jewish Question] (1976), and above all Emancypacja Żydów na ziemiach polskich [Emancipation of Jews in Polish Territories] (1987).

“Summing up his life achievements, Artur Eisenbach repeatedly emphasized the need to maintain a certain dose of neutrality. A historian's job is to coolly analyze the facts and look at events impartially. A historian must be attached to the truth” – writes Antony Polonsky. Towards the end of his life, Eisenbach quoted his master, Marceli Handelsman: “From us, historians, Poles expect only one thing – truth – even bitter, even brutal – clear truth, without getting confused in explanations or finding convenient explanations; real truth” [8].

Footnotes:

[1] Basic information follows the text: Aleksandra Bańkowska, „Inwentarz zbioru spuścizna Artura Eisenbacha. Lata 1918-1992” [Inventory of the collection, the legacy of Artur Eisenbach. The years 1918-1992], JHI Archives.

[2] Antony Polonsky, Artur Eisenbach a historia polsko-żydowska [Artur Eisenbach and Polish-Jewish History], trans. Daniel Grinberg, „Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego”, No. 4/1992, p. 7.

[3] Ibid., p. 9.

[4] Artur Eisenbach, Wstęp [Introduction], in: Emanuel Ringelblum, Kronika getta warszawskiego [Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto], ed. and introduction by Artur Eisenbach, transl. Adam Rutkowski, Warsaw 1983, p. 11.

[5] See: A. Polonsky, op. cit., p. 11.

[6] Łukasz Połomski, Nowosądeckie rodowody historyków. Ringelblum – Eisenbach – Mahler [Nowy Sącz roots of historians. Ringelblum – Eisenbach – Mahler], "Kwartalnik Historii Żydów" No. 256, December 2015, p. 595.

[7] This and the following quotes come from the article by Aleksandra Bańkowska prepared in 2014 for the website of the Jewish Historical Institute.

[8] See: A. Polonsky, op. cit., p. 12.