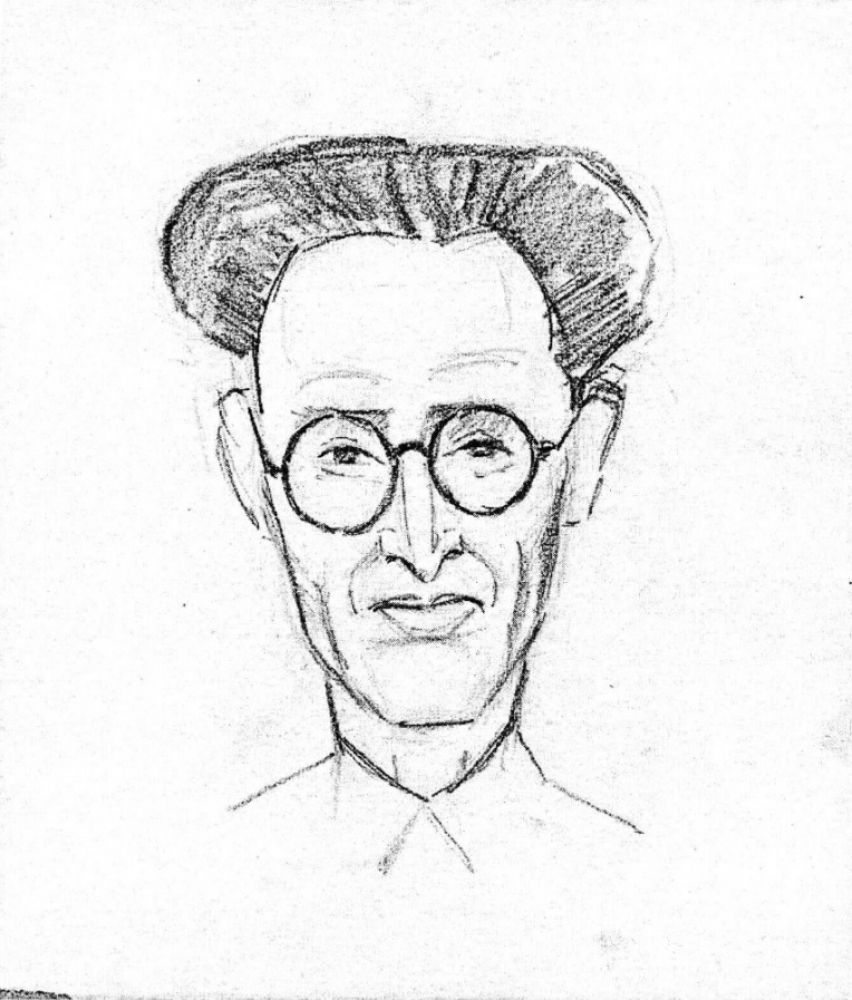

Gela Seksztajn-Lichtensztajn, portrait of Israel Lichtensztajn, Ringelblum Archive

Gela Seksztajn-Lichtensztajn, portrait of Israel Lichtensztajn, Ringelblum Archive

Israel Lichtensztajn was born in 1904 in Radzyń Podlaski, a town 100 kilometres southeast of Warsaw, to Jankiel, a merchant, and Dwojra. [1] He had three siblings: Jente (emigrated to Argentina), Szlomo (emigrated to Palestine), the youngest brother, Berl, lived with Dwojra in Radzyń.

Israel was educated at the Teachers’ College in Vilnius. From the early 1920s until the outbreak of World War II he collaborated with magazines such as “Arbeter Cajtung”, “Di Fraje Jugnt”. He was also the secretary of the editorial office of “Literarisze Bleter”, the most important Yiddish literary magazine published in the interwar period. He collaborated with the Philological Section of the YIVO Institute. From the 1920s Israel was also involved in Jewish political parties – first in Hashomer Hatzair, then in Poale Zion-Left. In 1931, he became a secondary school teacher, a year later he moved to Warsaw, where he became the headmaster of the Borochov school in the Praga district.

![portret_dziew_z_warkoczami.jpg [95.63 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/14/f1f6576d7549e4019fff63ee5e1f87ae/jpg/jhi/preview/portret_dziew_z_warkoczami.jpg)

In 1938, Israel married the painter Gela Seksztajn. They lived at 5/10 Nowolipie Street, then at 29 Okopowa Street. In 1940 their daughter Margolit was born.

“To bring out the beauty of every child.” See the collection of Gela Seksztajn’s works

In the Oneg Shabbat group

After the establishment of the Warsaw ghetto, Lichtensztajn became the headmaster of the Borokhov primary school at 68 Nowolipki Street. Dov Ber Borokhov (1881-1917) was a Russian Jew, leader of socialist Zionism and the Poale Zion party; institutions named after him conducted secular education under the banner of Zionism and socialism. In 1920, the party split and the “right” and “left” factions emerged; among the activists of Poale Zion-Left were Adolf Berman and Emanuel Ringelblum.

In the Warsaw ghetto, the Borokhov school was the “«apple of the eye» for the Poale Zion-Left party” [2] as Berman put it – illegal party press was printed there, illegal party meetings were held, and a children’s kitchen was run. It is in the basement of this school that the first two parts of the Ringelblum Archive were to be hidden.

![potwierdzenie_lichtensztajn.jpg [433.05 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/14/6077b6c50c95ace5e1bc357baf5f4c21/jpg/jhi/preview/potwierdzenie_lichtensztajn.jpg)

Emanuel Ringelblum “recruited many teachers to work in the Archive – Bernard Kampelmacher, Israel Lichtensztajn, Aron Koniński and Abraham Lewin. For many years they belonged to his milieu. He knew these people and could trust them,” [3] writes Samuel Kassow. Ringelblum also worked with Lichtensztajn in the Jewish Social Self–Help and the Yiddish cultural organization called Ikor. After the ghetto was established, Lichtensztajn continued to teach and cared to maintain a high level of education in the Borokhov school.

Israel Lichtensztajn, “as the guardian of the materials gathered in the Archive, had perhaps the most difficult and responsible task in the entire Oneg Shabbat group” [4] – emphasizes Kassow. – “From the moment the Archive was established, only he knew the place where the texts and documents were stored. Ringelblum made efforts to ensure that – if he or other authors of the Archive fell into the German hands – the secret remained safe.” [5] To minimize the risk of the materials being discovered by the Germans, Ringelblum concealed the actions of Lichtensztajn and his assistants from the rest of the group, so only the founder of the Archive and his secretaries Hersz Wasser and Eliasz Gutkowski knew where it was supposed to be hidden. [6]

Hide the Archive

On July 22, 1942, the Germans began mass deportations from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp. Ringelblum and Wasser ordered Lichtensztajn to bury the Archive. With the help of his two teenage former students, Dawid Graber and Nachum Grzywacz, Lichtensztajn hid the first part of the Archive in the basement of the Borokhov school. Menachem Mendel Kohn, the treasurer of the Oneg Shabbat group, who was looking for a shelter from deportation, came to them:

I decide to run to the kitchen of the Borokhov school, which is located near Gęsia Street, at 68 Nowolipki Street. They will certainly welcome me warmly there – I think. It was like that. When I came, the teacher Licht[ensztajn] and two graduates of the school, brave boys Dawid and Nachum, welcomed me very warmly. They made me hot coffee, prepared a place to sleep. I lay down in mortal fear. We evaluate the plan of today’s action and come to the conclusion that the bloodthirsty Nazi sadists will not be able to reach here today, to 68 Nowolipki. Just in case, we have prepared makeshift hiding places. [7]

Previously, Kohn was not allowed by his friends to the “shop” (forced labor enterprise) where he had a chance to avoid deportation. In turn, Lichtensztajn accused Ringelblum that during the deportation he was more worried about the protection of his own family than about the fate of Oneg Shabbat’s materials, but he steadfastly continued his assigned task. They could hear shots in the distance. Together with Graber and Grzywacz, they looked through the documents that came into their hands with fascination. “They raced against time by burying the Archives – who knew when the killers would show up – but they had managed to write down the last messages for future generations.” [8] They put their last wills into the metal boxes.

Now as I write this, you can’t stick your nose out into the street. It is also impossible to feel safe in one’s own flat. It’s been the 14th day of this terrible business. We almost lost touch with our other comrades. Everyone works on their own. Everyone cares for themselves as they can. The three of us remained: comrades Lichtensztajn, Grzywacz and me. We decided to write last wills, collect some material from the deportation and bury it. We have to hurry because we are don’t know how much time is left. Yesterday we worked on it until late at night [9] – wrote Dawid Graber on August 3.

I want my wife Gela Seksztajn, a talented painter, whose dozens of works have not been displayed, never saw the light of day, to be remembered. During the three years of the war, she worked with children as a tutor and teacher. She prepared decorations, costumes for children’s performances, and received awards. This time we are preparing to accept death. [10] – wrote Israel Lichtensztajn.

Graber and Grzywacz were transported to Treblinka the same week. “Gela Seksztajn, Israel Lichtensztajn and their little daughter did not die that week. They hid in the same building where Lichtensztajn hid the Archives, postponed their death for nine months,” [11] writes Kassow. After the defeats of the Germans on the Eastern Front and in Africa, they still had a shadow of hope that they would manage to survive the ghetto.

In February 1943, Lichtensztajn hid in the same place, in two large aluminum milk cans, the second part of the Archive. Metal boxes were found in 1947 – during five years underground water got into them, damaging many documents. But the cans found in 1950 saved the documents from flooding and destruction. In total, over 35,000 pages of documents of the Oneg Shabbat group were found. The third part of the Archive was to be hidden in the so-called brushmakers’ “shop” at 34 Świętojerska Street, but it was never found.

![czego_6_banka.jpg [1.59 MB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/14/6ef749c10481b517d12bba8f8aeabd02/jpg/jhi/preview/czego_6_banka.jpg)

Last days

Lichtensztajn, along with other members of the Oneg Shabbat group management, participated in preparations for armed struggle, such as collecting money to buy weapons for the Jewish Combat Organization. Ringelblum saw him for the last time two days before the outbreak of the ghetto uprising:

I met my comrades [Natan] Smolar and Lichtensztajn for the last time on Sunday, April 17, 1943 in Brauer’s “shop” in Nalewki Street. The last action took place during the night. We said goodbye at the gray dawn. Comrades Smolar and Lichtensztajn decided to sneak into Hallmann’s “shop”. What happened to them on the way – I do not know. They probably did not reach 68 Nalewki, as there were a lot of gendarmerie posts, SS and Ukrainians. They were probably killed on the way like thousands of other Warsaw Jews. [12]

Kassow adds that Lichtensztajn probably died at the beginning of the ghetto uprising. It was then that Gela and Margolit were also murdered.

![Gela_Margolit.jpg [41.63 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/14/90f469a922badfa809b9d484bb791139/jpg/jhi/preview/Gela_Margolit.jpg)

The paintings, drawings, photographs and last will of Gela Seksztajn-Lichtensztajn are among the materials that have survived in the first part of the Ringelblum Archive. It is the largest collection of one artist stored in the ARG.

Me and Grzywacz, under the watchful eye and with the help of comrade Lichtensztajn, were digging pits for boxes with documents with great enthusiasm. With what joy we accepted each new material…

We felt our responsibility. We were not afraid of the risk. We realized that we were making history. And this is more important than our life. [13] – wrote Dawid Graber.

“The words of David Graber became the title of our exhibition: What we’ve been unable to shout out to the world. They were written in the original language, in Yiddish, on the entrance wall. The activists of the Archive spoke Yiddish. The inhabitants of ghettos spoke Yiddish. Those words screamed then, they still scream today,” writes professor Paweł Śpiewak. – “They call for the preserved documents to be read, studied, understood, lived, so that they become our memory and our common heritage.” [14]