- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

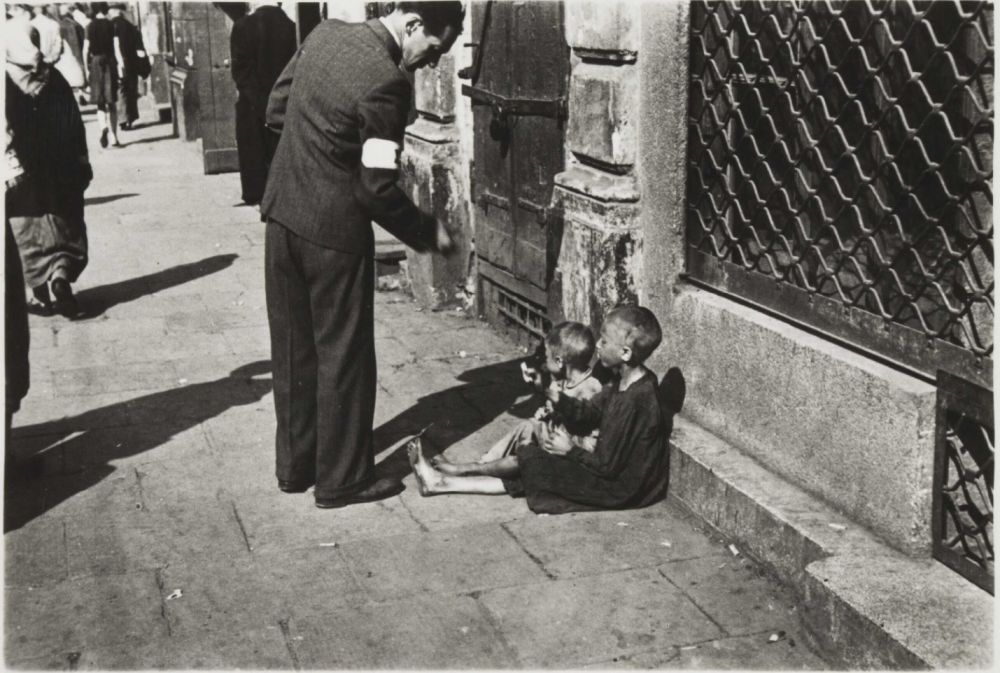

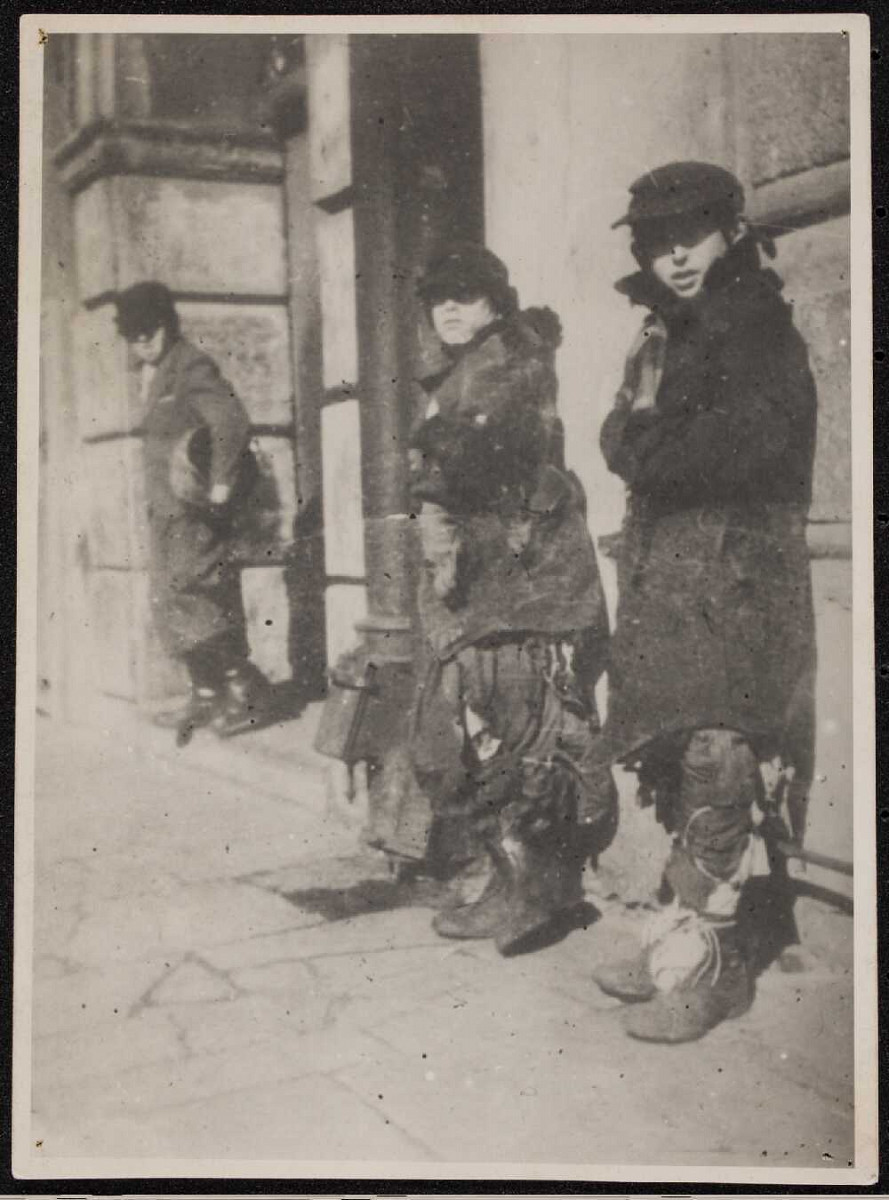

Little children begging in the street of the ghetto. Photo by Willy Georg, summer 1941 / JHI collection

Emanuel Ringelblum called her an angel living on Earth, an impersonation of kindness in one of his essays. Rachela Auerbach remembered that Roza was one of the brightest individualities in the Warsaw Ghetto, one of the most beautiful people she had met in her life. [1] Lea Rotkop called her the closest friend of a Jewish child, who measured her own life against the fate of those who suffered the most and required immediate help – the youngest inhabitants of the Warsaw Ghetto. [2]

Who was Roza Simchowicz, someone who despite being quiet like a mouse and deeply lost in thought had left such a strong mark on the hearts of people who knew her and worked with her? [3]

Roza Simchowicz (known also as Roza Symchowicz, Róża Simchowicz, Rozalia Simchowicz) – was born in 1887 in Slutsk, Belarus. She came from a rich, respected Jewish faily from Russia. Her father, a Russian Jew, educated and enlightened „maskil”, was writing articles about Jewish law for Russian periodicals. Mother came from Lviv, the way she managed the house resembled a nobility mano. [4] Roza’s brother, Jakub Simchowicz, was a historian and translator from Hebrew. He was teaching in a Hebrew gymnasium in Łódź and died in 1926.

fter the father died in 1896, the family moved to Minsk, where Roza attended school. Later, mother sent her to Petersburg for an „advanced course”. At the age of 17, Roza joined the socialist movement and was soon arrested. According to her friend Lea Rotkop, in prison she didn’t want to make use of any privilege and took care of her cellmates. [5] She was freed on the condition that she would move abroad. She went to Switzerland, where she joined the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Pedagogical Institute in Geneva. At the same time, she enrolled into the philosophy course at the University of Geneva.

She spent World War I in Vienna, where she worked with children of Jewish refugees. In 1919, she moved to Vilnius, where she was running courses organized by the Society for Protection of Health of the Jewish Community in Poland and the Local Jewish Committeefor Aid for the Victims of War in Vilnius.

She co-founded and managed the Jewish School for Teachers in Vilnius (1921) and was active in the structures of YIVO in Vilnius, playing an important role in the movement promoting teaching in Yiddish language in schools.

In independent Poland, the necessity to establish a Jewish academy for teachers became a priority issue. Roza was strongly involved in these pursuits. She takes part in all these activities, she is everywhere, speaks everywhere, her voice saying important things out loud can be heard everywhere. [6] She participated in the first meeting of Jewish secular schools in the Polish Republic (1921).

Roza became the co-editor of a monthly magazine for teachers, Di naye shul (New school), in which shere published pedagogical articles, as well as in Shul un heym (School and home) magazine. In 1923, she was forced to leave Vilnius because of her nationality. For some time, she was living in Vienna, later moving to Berlin. After three years, she returned to Poland and settled in Warsaw, where she began to cooperate with CISZO (Central Jewish School Organization). She was responsible for managing secular schools in Poland and working with the pedagogical section of YIVO in Vilnius. Additionally, she was involved in various social initiatives such as collecting money for mental health centre in Vilnius. [7]

Emanuel Ringelblum recalls her: Tall, slim, with a kind, friendly face, silver-dusted hair, about 50 years old. Thanks to her teaching skills, she was working for a longtime for CISZO. She was traveling between cities and towns, telling Jewish teachers how to love Jewish children and bring them up in the spirit of secularism and humanism. Deeply in love with Jewish past, she wanted to link it with present day. Humble, quiet like a mouse, she walked around lost in thought, like a human being from another planet. It’s impossible to describe directly how much secular Jewish education in Poland owes to her, especially in the countryside, where teachers drew so much from her rich experience, her exceptional knowledge in the field of upringing problems, but above all, from her vast intuition. She was a born teacher. Miserable and solitary, an impersonation of kindness, she dedicated herself completely to the world of children. [8]

In 1937, she was representing CISZO at the International Teachers’ Meeting in Paris. She gave a lecture on Jewish education in Poland, received enthusiastically by the audience. She was also actively organizing the Jewish pavillion at the World Fair in Paris.

Despite all her experience and great contributions, CISZO lacked funds to support a special instructor, which made her give up teaching soon before World War II. She was making a living by private language lessons. [9] Roza Simchowicz’s situation had worsened drastically when the war began. According to Pola, she was living in poverty. [10] She was resettled to the ghetto, where she found employment in Centos. World War II had begun. Roza Symchowicz returned to her „first love”, to Jewish children. She joined the Centos. Along with various Jewish actors, she tried to introduce Yiddish language classes to Centos institutions. [11]

Roza became responsible for „children’s corners” hosted by house committees, where children were offered food and space to play. She was running a course for carers and giving lectures on upbringing in Yiddish language. Centos commissioned from her also didactical materials and books for children’s institutions. She has no funds for this, but her kind and mild attitude encouraged people to support her. She is glowing with joy when she manages to find the right book, poem, other reading material. (…) She wants to spark love for Yiddish language in people’s hearts (…) She is working quietly, humbly, without noise, mess or self-promotion. [12]

As the head of Yiddish culture department (management of the Central Committee for Children’s Events) Roza was also running a library for children. Together with Barbara Berman, she was organizing promotional compaigns for children’s books in Yiddish. In cooperation with JIKOR (Jewish Cultural Organization), she was teaching Yiddish language and literature.

Eventually Centos commissioned her to manage the homeless children’s department. She took on herself the most difficult task – qualifying children for boarding houses.

In one of Centos rooms, at one of the desks, sat a tall, slim woman with silver hair and giant eyes radiating kindness, and with a friendly smile (…) due to lucky coincidence, she had to put her desk in the Centos waiting room because of lack of space. Mothers with children seeking help gather here; here, she sees the entire poverty and misery of the Jewish child. [13]

Ringelblum wrote:Comrade Symchowicz is qualifying candidates, hearing every child separately, getting to know them, and eventually she directs them to booarding houses. Children of the street are dirty, infected with lice, most of them suffer from typhus. [14] According to Lea Rotkop, despite suffering from hunger, she was giving her breakfast to the children. She has a special love for them, talks to them like a loving mother. [15] RIn orderto remain as close as possible to suffering children, Roza didn’t agree to install a barrier separating her from children infected with typhus.

Officials (…) are setting up barriers in offices in order to stay separated from the street children and to avoid dangerous lice, carriers of typhus. The great friend of children, an angel of Earth, compassionate in suffering, Roza Symchowicz doesn’t understand how one could, from human and pedagogical point of view, separate themselves from children, these poor lambs seeking support from Centos. She does not agree to install a barrier between her and the street children. When these heartbroken children were coming to Roza, she was stroking their heads, supporting them and helping to the extent she could. [16]

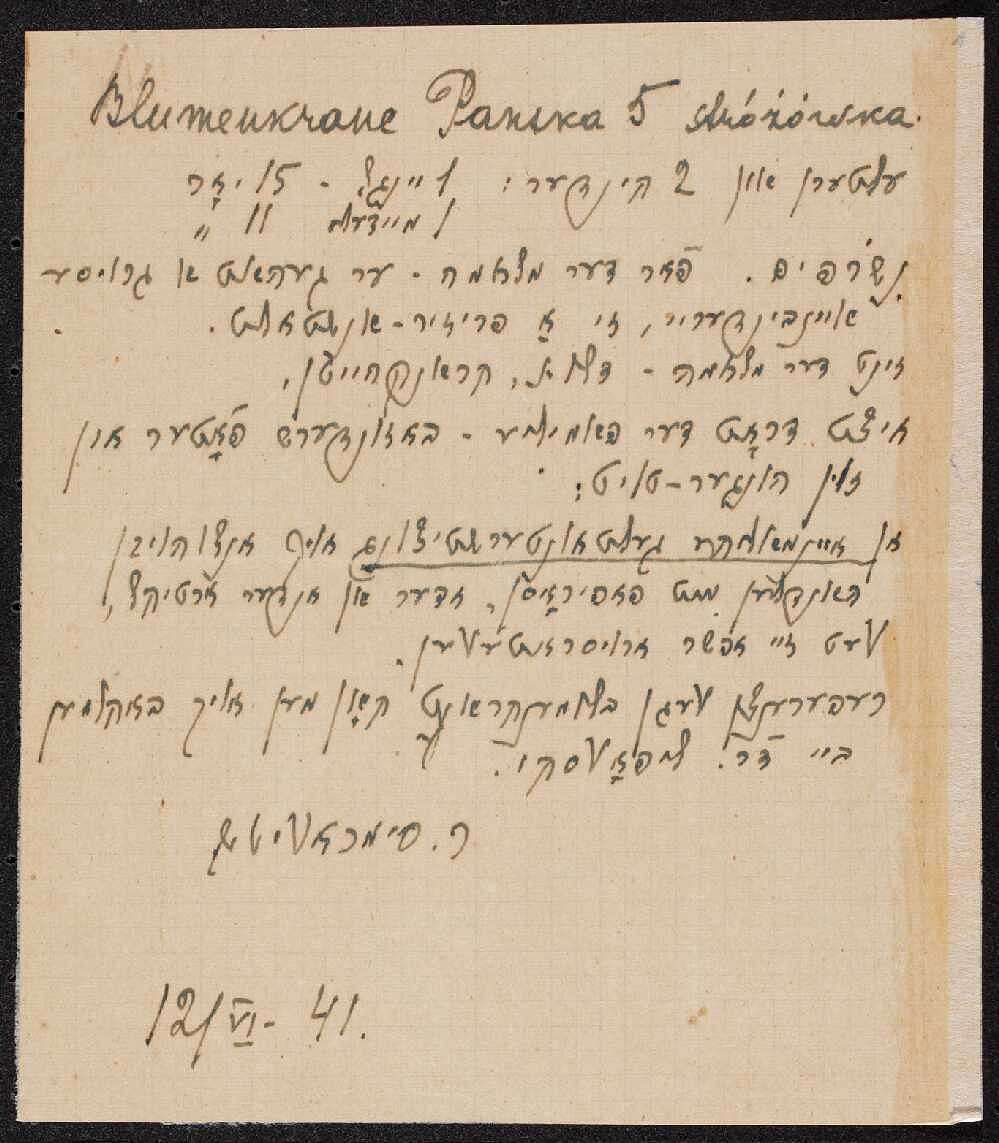

Eventually, she became infected with typhus as well. Ringelblum writes that she refused help from Joint, believing that there are others more important than herself, who have contributed more to society. [17] She died in November 1941. The exact date of her death remains unknown. She was buried on 2 December 1941. Ringelblum writes that she had an impressive funeral.

(translated by Olga Drenda)

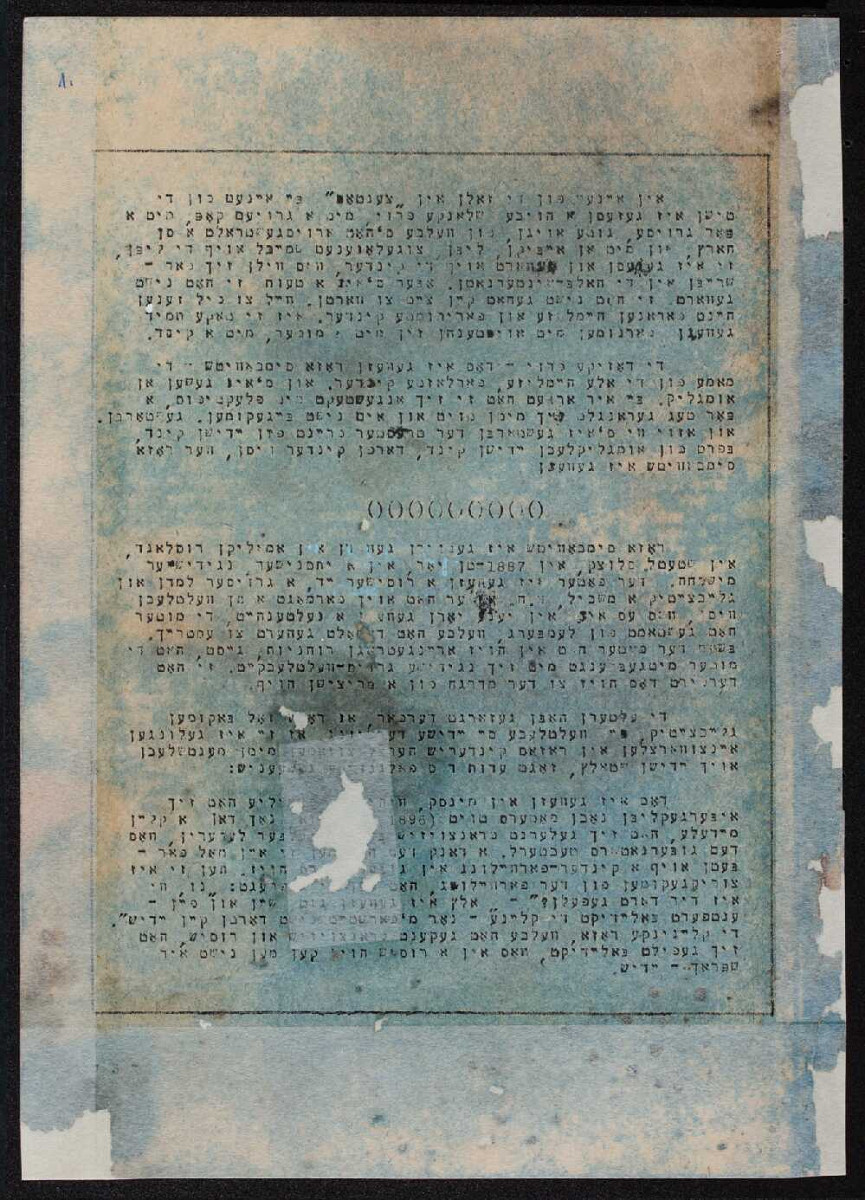

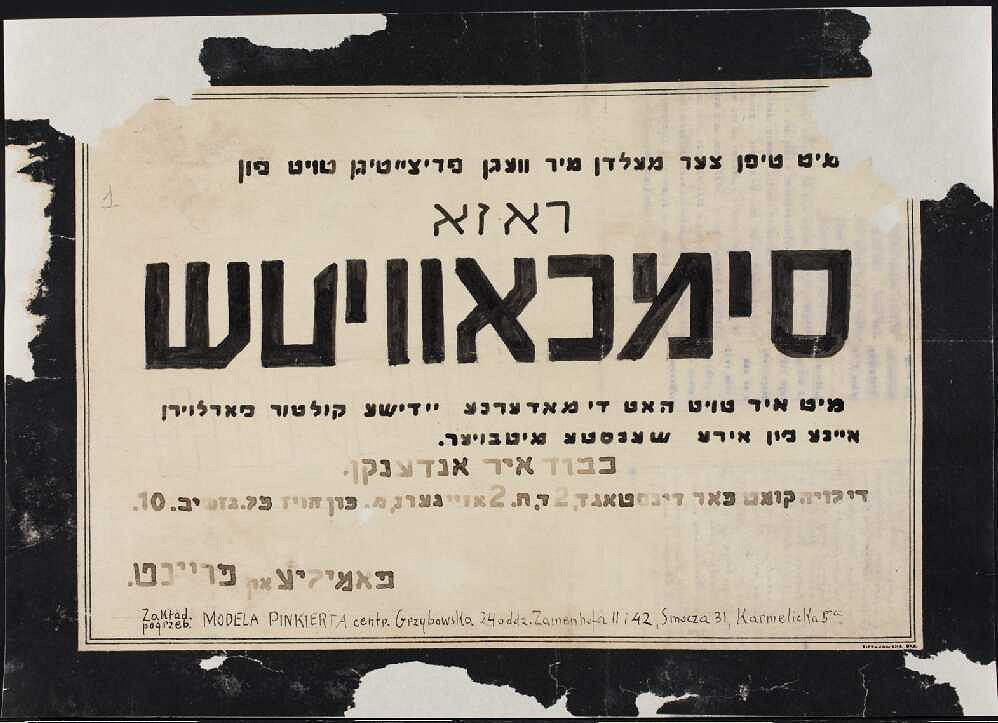

Obituary: With deep sadness, we inform you about the premature death of Roza Simchowicz. With her departure, contemporary Jewish culture had lost one of its greatest contributors. May we honor her memory. The funeral will take place on Tuesday, 2nd this month (December 1941) beginning from her home, pl. Grzybowski 10. Family and friends / The Ringelblum Archive

Hundreds of friends and acquaintances came to give the last goodbyes. Due to strange chance, the hearse with the body escaped us. The humble Roza was embarrassed with the impressive funeral we organized for her, and ran away. This is how it happened: we have gathered in the „small ghetto”, in front of her house, and walked along with the hearse. The „small ghetto” was linked to the „large ghetto” in two places. The pedestrian path led through a wooden bridge over the Chłodna street, which was aryan and divided the „small” and the „large” ghetto. Carriages were going down the aryan side, on Chłodna street. We have agreed with the coach driver that he will wait with us on the other side of Chłodna. It happened differently. He went directly to the cemetery, not waiting for us in the agreed place. He went directly to the cemetery, not waiting for us. Roza’s funeral was probably the last one with a speech. A small group of friends passed through the border at the cemetery, which was located on the aryan side. The JIKOR society published a hectograph paper dedicated to Roza. [18]

From autumn 1941, the children’s library at 67 Leszno street was named after Roza Simchowicz. In the room where Roza Simchowicz worked, crying could have been heard for many days after her death. [19]

Footnotes:

[1] Warszewer cawoes. Bagegeniszn, aktiwitetn, gojroles 1933–1943, Tel Awiw 1974, p.254 [after:] Rachela Auerbach, Pisma z getta warszawskiego, transl. Karolina Szymaniak, Anna Ciałowicz, JHI, Warsaw 2015, p. 118.

[2] Lea Rotkop, Roza Simchowicz, Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 2, p. 240, 245.

[3] The only photograph of Roza Simchowicz (probably) is available at: http://eng.thepartisan.org/document/68521,0,6795.aspx

[4] Lea Rotkop, Roza Simchowicz, op. cit, p. 241.

[5] Ibidem, p. 242.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] Lerer Yizker Bukh (Memory Volume for Teachers) released in New York in 1954 contains a few remembrances from her students: This was a beautiful, pure, religious soul, modest and august in her modesty, with profound intelligence, with a fine heart and with the talent to appreciate people…. Only certain individuals knew that she deeply religious. One could see her at High Holiday time in the women’s synagogue with a holiday prayer book in her hands and her face irradiated from the sanctity of prayer. She was not bashful about praying like all the Jewish wives. Pure souls have nothing to be ashamed of.” And, Feyge Barakin-Melamdovitsh noted: “I met Comrade Simkhovitsh the first time in 1921, when I arrived as a pupil at the Vilna Jewish teachers’ seminary. I noticed a slender, young woman, with an oblong face, a proud head, with short cut hair, and a pair of flaming, large, wise eyes. I have never once in this life forgotten those eyes…. Each time when I would enter her room, my heart beat with a special impetuousness. It was not fear. It was the sense of reverence, the feeling of solemnity that you experienced every time when you met eye to eye with Roza Simkhovits [after:] http://yleksikon.blogspot.com/2018/04/roze-simkhovitsh-roza-simchowicz.html

[8] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, vol. 29a, p. 231–233.

[9] Ibidem.

[10] Lea Rotkop, Roza Simchowicz, op. cit, p. 243.

[11] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, op. cit., p. 231–233.

[12] Lea Rotkop, Roza Simchowicz, op. cit, p. 244.

[13] Ibidem, p. 240–243.

[14] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, op. cit., p. 231–233.

[15] Lea Rotkop, Roza Simchowicz, op. cit, p. 245.

[16] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, op. cit., p. 231–233.

[17] Ibidem.

[18] Ibidem.

[19] Lea Rotkop, Roza Simchowicz, op. cit, p. 246.

Bibliography:

The Ringelblum Archive, Dzieci – tajne nauczanie w getcie warszawskim, vol. 2, ed. Ruta Sakowska, JHI, Warsaw 2000.

The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, vol. 29a, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, JHI, Warsaw 2018.

Rachela Auerbach, Pisma z getta warszawskiego, transl. Karolina Szymaniak, Anna Ciałowicz, JHI, Warsaw 2015.

http://yleksikon.blogspot.com/2018/04/roze-simkhovitsh-roza-simchowicz.html

http://eng.thepartisan.org/document/68521,0,6795.aspx