- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Władysław Szlengel. Photo from the collection of the Jewish Historical Institute

What do Władysław Szpilman, Mieczysław Fogg, Julian Tuwim and Marysia Ajzensztadt, called the Ghetto’s Nightingale, have in common? Not a what but a who – Władysław Szlengel, the star of pre-war theatres and cabarets, author of lyrics sung by all of Warsaw, poet.

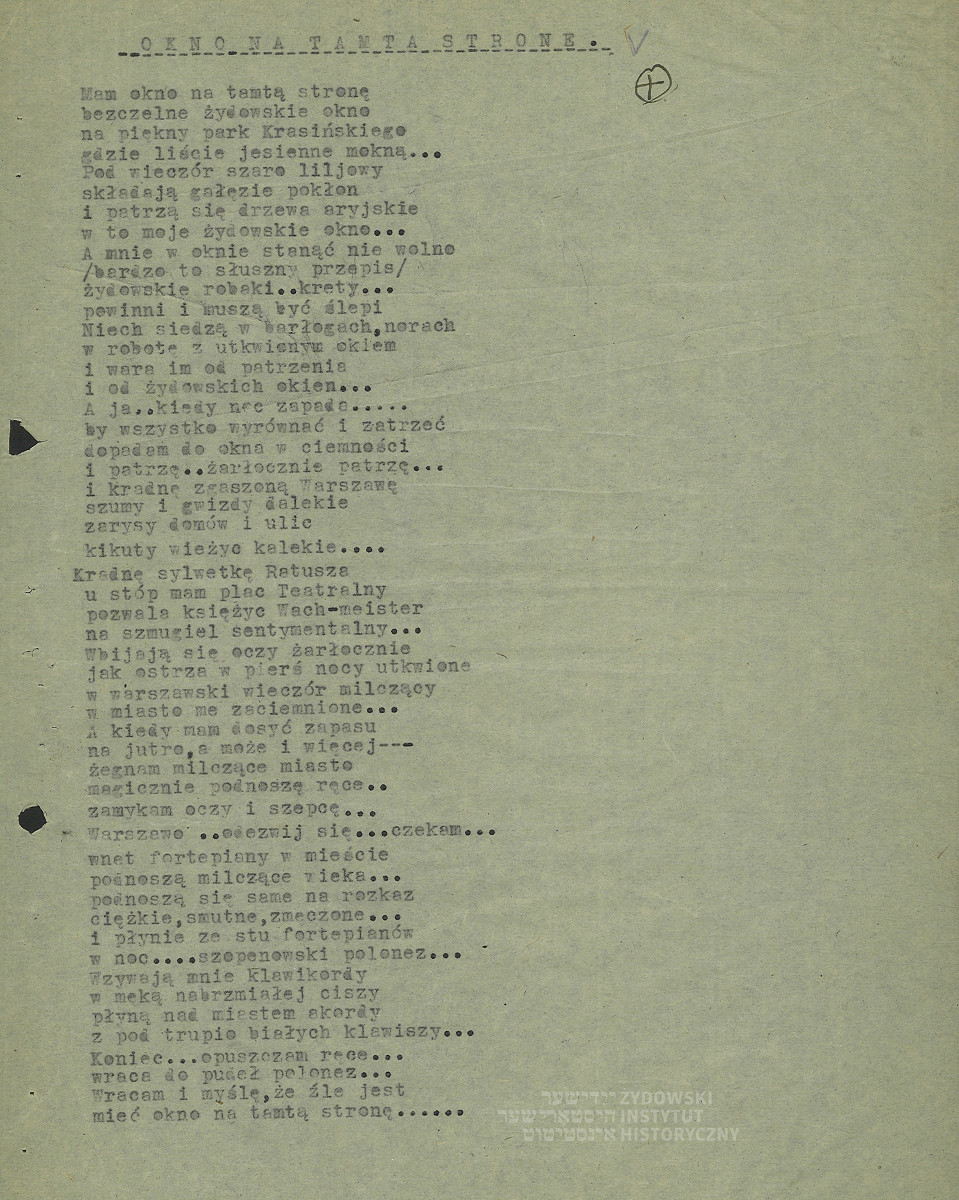

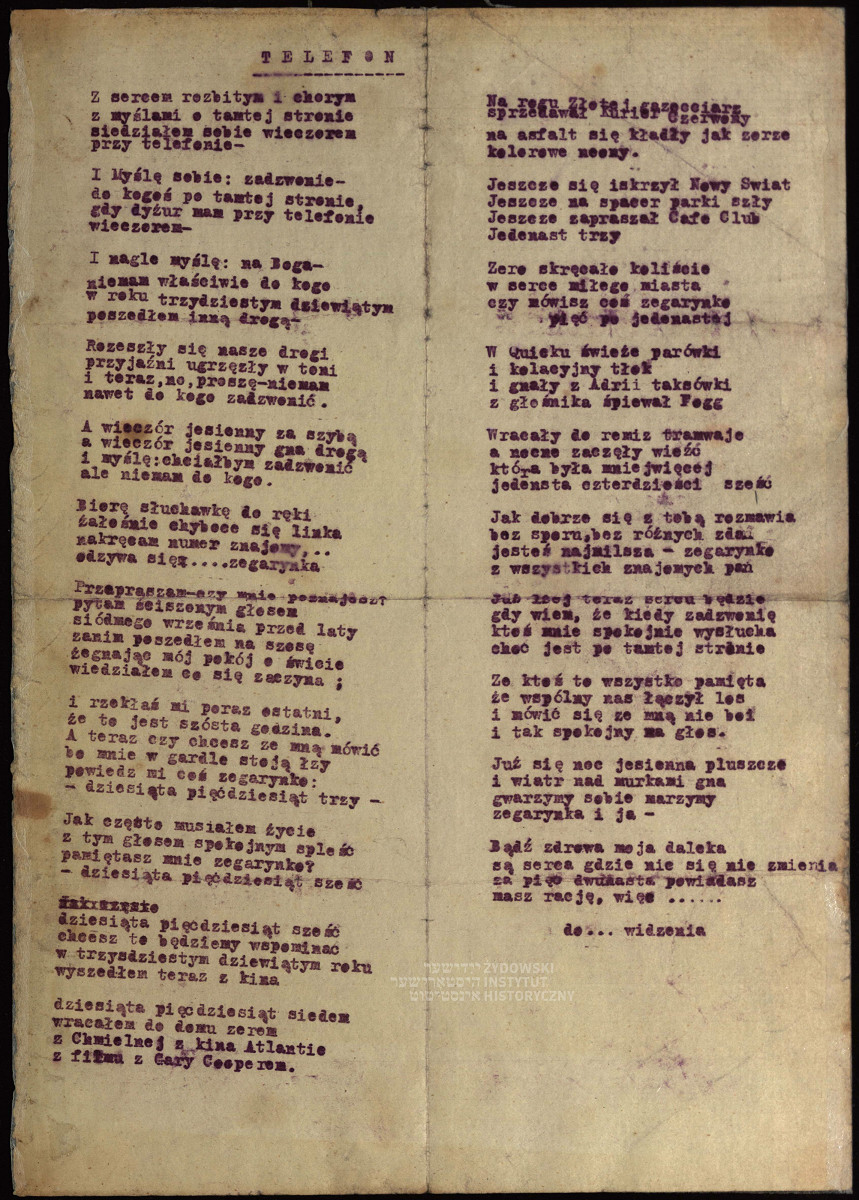

Władysław Szlengel was born in 1914 in Warsaw, and though he lived elsewhere for a while, he never truly left. The capital city was the central theme of his work: before the war – folk-stylized, light and satirical, with some of the most popular examples being Panna Andzia ma wychodne (Miss Andzia’s Day Off, music by composer Bolesław Mucman), Chodź na piwko naprzeciwko (Let’s have a beer, across the road) or Jadziem, panie Zielonka (Let’s go, Mr. Zielonka); during the war – expressing the bitter taste of being locked up in the ghetto and the desperate, futile attempts to find a hiding place on the Aryan side for his wife and him.

Szlengel began his short but intense career in the press, according to what Magdalena Stańczuk writes, a very specific type of press: “Polish language Jewish press.” As early as 1930, he published his poetry in Nasz Przegląd (Our Review). His politic writings were published in the Robotnik (Laborer). The third publication the young poet had his texts in was the very popular inter-war period satirical weekly Szpilka (The Pin, published again after the war)." It was in The Pin’s offices that Szlengel met the man who later became his friend and mentor – Julian Tuwim, already famous at the time.

The next stage of Władysław Szlengel’s career was the cabaret. He co-created and performed in "13 Rzędów" (13 Rows) and "Ali Baba", among others.

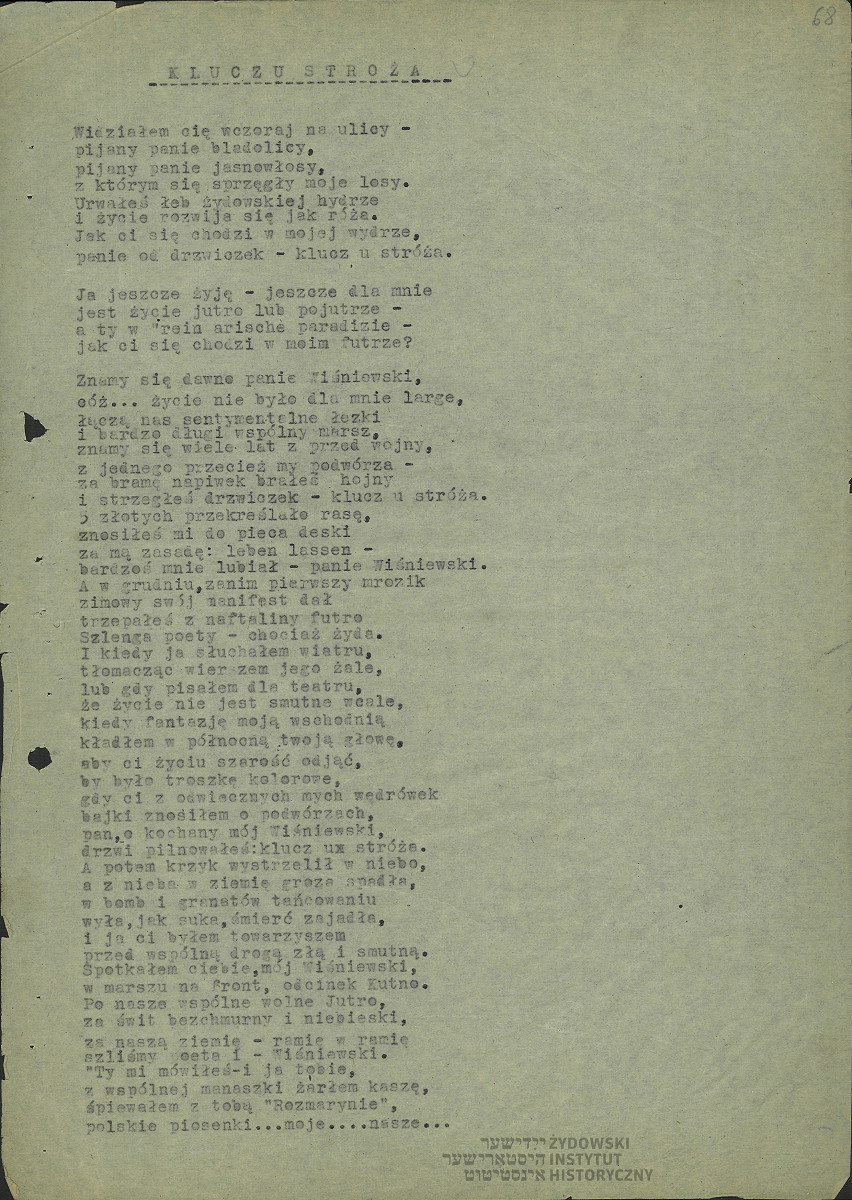

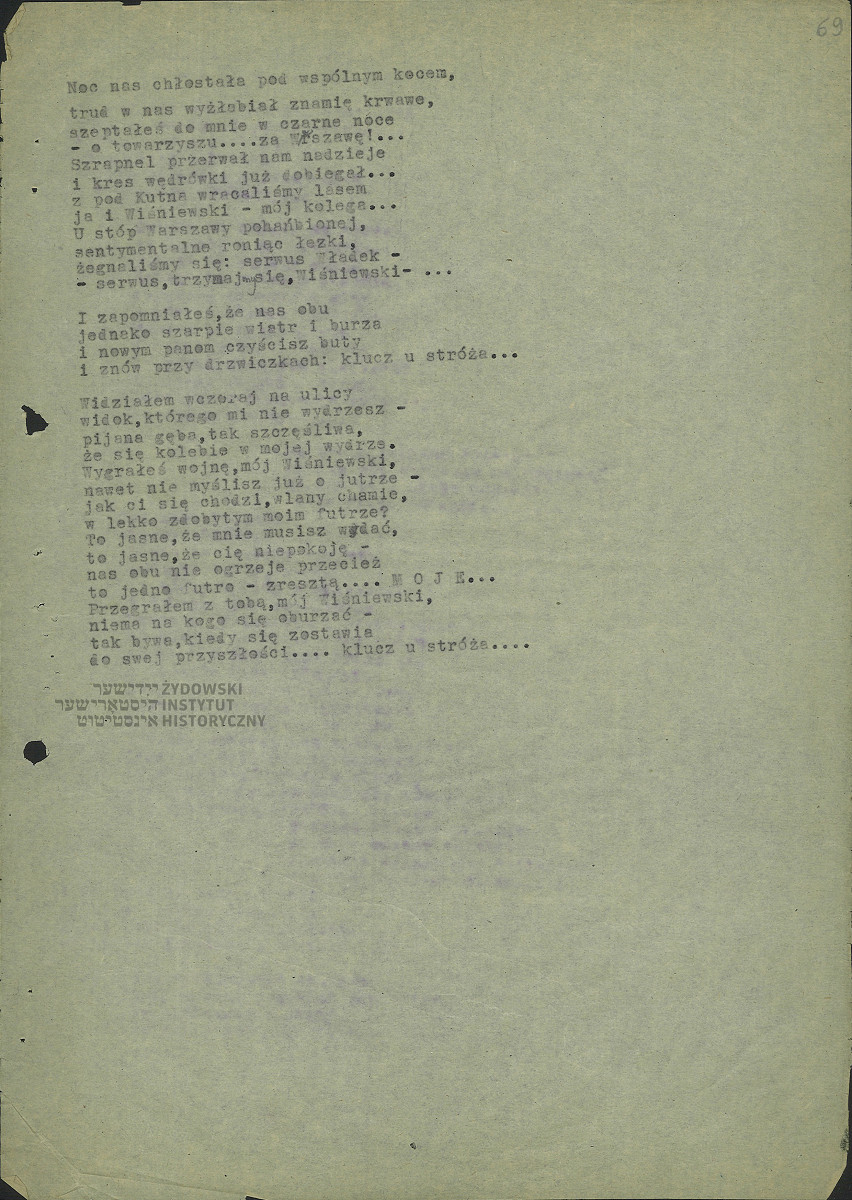

Szlengel’s brilliant carreer was (briefly) interrupted by the start of the war. He most likely took part in the Polish defensive war of 1939 and was among the defenders of Warsaw. This is proven by the undoubtedly autobiographical poem Klucz u Stróża (A Key Kept by the Watchman) but there is no formal evidence to corroborate this. After the city's capitulation, Szlengel and his wife spent a few months in the Soviet-occupied Białystok. However, he returned to Warsaw and – according to Ryszard Sielicki – took residence in the tenement house at 14 Waliców Street, which became part of the ghetto after the Jewish living quarter was closed off on 16th November 1940.

In the ghetto he became part of the most prestigious and ambitious cabaret – Sztuka at 2 Leszno Street. He performed there together with Wacław Teitelbaum, Wiera Gran, Pola Braun, Diana Blumenfeld, Marysia Ajzensztadt, Andrzej Włast and pianists Adolf Goldfeder and Władysław Szpilman. According to Magdalena Stańczuk, “this star-studded cast succesfully continued pre-war traditions and, through sentimental hit songs, fulfilled the expectations of the audience searching for refuge in the past. However, the place's biggest attraction soon became the Polish-language satirical cabaret called Żywy dziennik (The Live Journal), created by the artists who performed there. Performed every week, this spoken chronicle of the ghetto was extremely popular, largely due to the poems written by Szlengel using lively and colorful language, and the witty monologues he gived. Its success was based on their references to everyday life in the ghetto and the sharp satire used to comment on current events. This commentary discussed everything: Jewish police, order-keeping services, and relations in the community. Szlengel (…) ‘with great fervor fulfilling the role of announcer’ was unquestionably the star of the Leszno act. He drew in audiences like a magnet.”

The difficult reality od everyday life in the ghetto soon left a strong impression on Szlengel’s work. He made contact with the creator of the Underground Ghetto Archive, Emanuel Ringelblum. The artist’s presence “made a mark on the Archive’s structures, as evidenced by the multiple examples of his work in the surviving Oneg Shabbat documents”. That was the end of Szlengel’s “café period”. It ended with the liquidation of the Ghetto (Grossaktion Warsaw) between July and September 1942, when Warsaw Jews were deported to German extermination camps. Szlengel witnessed Janusz Korczak’s march with his pupils to the Umschlagplatz. His poem Kartka z dziennika akcji (A Page from a Journal During the Action) is the first, moving piece commemorating this event.

Szlengel and his wife managed to avoid deportation. Luckily, he was assigned to one of the German enterprises using Jewish slave labor – Toebbens’ factory. He and his wife began living in the so-called “brush shop” at no.34 Świętojerska Street. One of his neighbors was Marek Edelman.

“Szlengel dedicated himself completely to writing.” – writes Magdalena Stańczuk. – “He resurrected, on his own this time, the Live Journal, filled with social satire, which he read out during literary evenings on Saturdays. The fame of the so-called 'farces' quickly went beyond the small room of the apartment in Świętojerska Street and began bringing in a wider and stranger audience, because together with the brush-shop workers and the management, some of the ghetto's notable people started showing up at Władek’s performances.”

Alongside his artistic activities, Szlengel also collected interesting documents and notes, planning to describe the life in the ghetto. However, he ran out of time. He was interrupted by the selection that began on January 18, 1943 in the brush-shop. He described it in his moving text Co czytałem umarłym (What I was reading to the dead).

After that, Szlengel lost hope. He managed to leave the ghetto a couple of times under the guise of transporting products from the factory. He searched for help, support and a hiding place among his friends on the Aryan side.

He searched in vain. Finally, with his wife and a group of Jews, he hid in the Szymon Kac bunker at 36 Świętojerska Street. On May 8, 1943, during the Ghetto Uprising, the Germans discovered the bunker. All the Jews hiding in it – 130 people – were executed on the same day. Władysław Szlengel was among them.

Magdalena Stańczuk describes the poet’s death: “(…)he died uneventfully, without the shine of a hero, without fireworks, just as millions of nameless victims (…), like thousands of innocent, simple people whose lives and deaths he managed to preserve in his poetry.”

The text is based on Magdalena Stańczuk’s book Władysław Szlengel. The Unknown Poet. A Selection of texts published in 2013 by Bellona and the documents collected at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.