- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

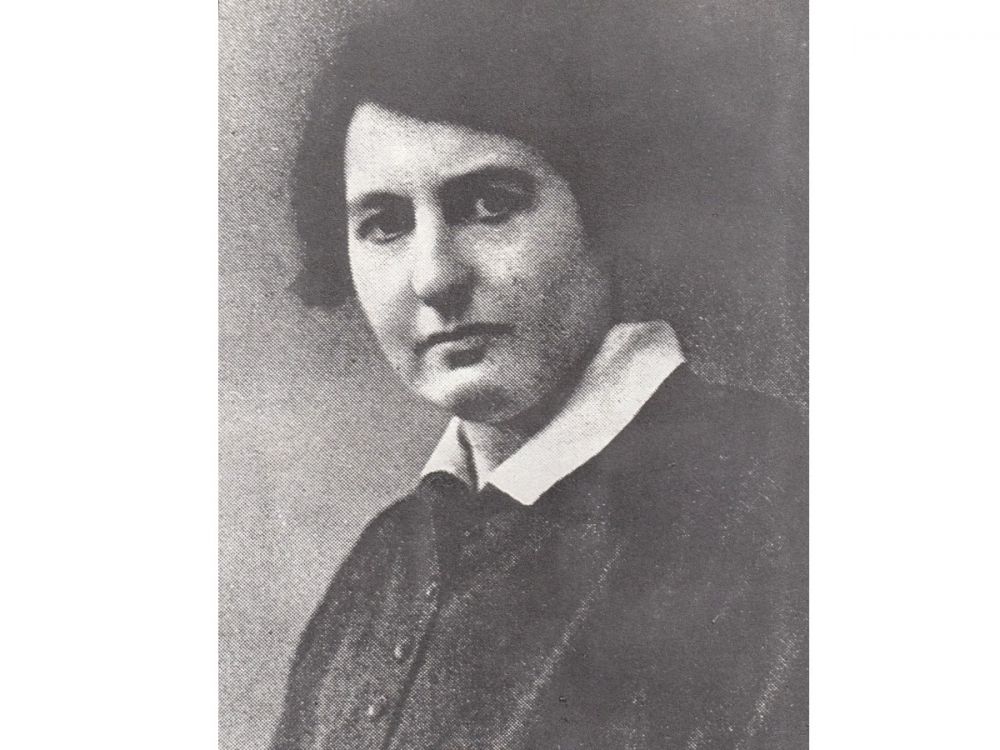

Stefania Wilczyńska / Wikipedia

‘Mrs. Stefania Wilczyńska usually remains in the shadow of the Old Doctor but anyone who knew the Orphans’ Home (Dom Sierot) knows that Korczak would never have been able to write and work as much as he did had Mrs. Stefa not taken on the burden of caring for the orphanage’s existence and its everyday workings.’ – remembered Ida Merżan, a dormitory student and associate of the Orphans' Home.

‘Mrs. Stefa, born in 1886, finished school in Warsaw and then studied abroad. After returning to Poland she began working – against the wishes of her wealthy family – at the cramped and dirty orphanage at Franciszkańska Street. Later Korczak joined this orphanage and they worked together from that point until the end. Together they built the beautiful house at Krochmalna Street, together they brought to life the self-governing system created by Korczak. During the First World War, when the children were having a hard time, Korczak was not with them – he was treating soldiers. However, Mrs. Stefa was always there for the children during rough times, she suffered hunger and typhus with them. She never “went anywhere without the kids”, she went with them and Korczak to the ghetto and then to Treblinka. Mrs. Stefa was the guardian angel of the bursa (”bursa”, or dormitory, was the nickname for the apprentice educators’ program in Korczak’s institution, where they taught and counseled the children in exchange for room and board) children and the Doctor.

![korczak_wilczynska_zih.jpg [143.00 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/5/24/8661a3f62e90bf3d1817c05f6a24ab70/jpg/jhi/preview/korczak_wilczynska_zih.jpg)

In the eyes of the pupils

Mrs. Stefa was with us, dormitory students, all day long. She got up before us, was the last to go to bed, she kept working even when she was sick. She was present at every meal, taught us how to make bandages, bathe children, cut hair etc. Tall, in a black apron, with a short, masculine haircut, always attentive and alert, even during resting time she was mindful of each child and dormitory student. She would often interrupt an interesting conversation to instruct one of the youngsters to remind one of us, or one of the children, that it was almost time to go to school. She knew perfectly well who among us would lose track of time when absorbed in their work. During meals she would sit where she could keep her eye on all the children and would often leave her table to teach a new child how to hold a slice of bread or spoon, what to use to wipe spilt soup. At night she would get up to tuck up the children, take the ones who might wet the bed to the bathroom, find out why someone is moaning in their sleep.

The Home was full of Mrs. Stefa. We could always feel her regard, her care. She would even remind us of duties we had beyond the Home.

Mrs. Stefa loved nature and knew how to instill children with this love. The house at Krochmalna Street was full of potted plants. In Gocławek, where the children from Krochmalna Street and other orphanages spent their summers, Mrs. Stefa would organize walks at twilight (after bath time) around the camp or to the forest to show the children the beauty of nature and teach them how to appreciate it.

She had a tender heart, a wise, open and perceptive mind. She knew how to reach anyone. She wrote to one of the lonely mothers, whose children had all left to work in orphanages, You are not allowed to regret them leaving you, for such is the fate of us, the old, that the birds fly off into the world. We can only be glad when they have something good to fly off with.

To one of her former wards, who lost a child, she wrote a long and heartfelt letter, full of sympathy and respect for another person’s pain: My dear Child! I will neither console nor convince you. That will be of no help to you… No one nor anything can console you after such a tragedy. Only time and work can help. I send you a tight, tight embrace, like the ones I would give you when you were young and something troubled you.

![Krochmalna_Street_orphanage.PNG [124.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/5/25/a7f76441f40a86c0624aa51033bdd720/PNG/jhi/preview/Krochmalna_Street_orphanage.PNG)

Mrs. Stefa had her faults as well. She liked pretty and talented children. She did not hide this love. It made other children jealous and dissatisfied, they felt she was unfair because she was honest. But when the children grew up and left the Orphans’ Home, they would only have pleasant memories of how Mrs. Stefa welcomed them and bathed them for the first time, how she nursed them through illness and comforted them at night when they had a bad dream. They would forget the unpleasant things.

Mrs. Stefa extended her care to anyone living in the Home, and so she also cared for Doctor Korczak. Busy with his scientific, social and literary work, he had no time to think of clothes and many other everyday necessities. Mrs. Stefa helped him with that.

So we were all surprised by I. Zyngman’s (Stasiek) book Janusz Korczak wśród sierot [Janusz Korczak among orphans], which he wrote under the influence of childish emotions he still had. His memories reflect a negative attitude to Mrs. Stefa. And the attitudes of Mrs. Stefa’s former charges are best reflected by the letters written to her from all around the world (The United States, France, Brazil etc.) and the Saturday meetings of the former pupils visiting the Orphans’ Home.

Balls

Mrs. Stefa took particular care of Janusz Korczak. She believed in his genius. She would wonder at his greatness going unnoticed, predicted that his ideas would become popular and triumph. She not only implemented his system and methods but also protected him, and the children, from coming in contact with the philanthropists. I remember the preparations for the ball organized by the “Help for the Orphans” Association. The proceeds from the ball went to the Orphans’ Home. Mrs. Stefa was busy. Constant phone calls, visits, showing visitors around. Neither the Doctor nor any of the children took part in this or were present at the ball. Mrs. Stefa took on the burden of the preparations. Nacia Poz and Rózia Lipiec assisted her. They were both former wards of the Orphans’ Home and in 1928 its employees. Korczak only inquired about the preparations, and was of course most interested in what the proceeds would be.

Mrs. Stefa kept Korczak away from the philanthropists. Korczak had to rely on philanthropy but could easily offend or show the door to any donor. The entire burden of interacting with the wives of lawyers, doctors etc. rested on the shoulders of Mrs. Stefa. Like a guardian angel, she protected the Doctor, trying to help with his literary work, lectures etc.

![wilczynska_yad_vashem.png [623.81 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/5/25/20a09c23760ab31519c04e97589384ab/png/jhi/preview/wilczynska_yad_vashem.png)

Korczak and Mrs. Stefa would also not allow their children to act as “poor orphans” grateful from the donations. To understand this you need to know how humiliating it was when the children from other orphanages would clean the houses of the rich, babysit their children and perform various menial tasks for them.

Not only were Korczak’s children not involved in the philanthropy but also any events, like balls or dances, were kept from them. The children were not used to assist with this work, were not presented as “poor orphans” to arouse sympathy and beg for money. No ball, no fundraising party was held at the Orphans’ Home. The children were not aware of the preparations, the hopes Korczak and Mrs. Stefa had for these balls.

Mrs. Stefa was close to Korczak, I don’t know how close. I do know that she was the first person he would share his impressions and ideas with, she was privy to all his endeavors. I do not know, I cannot judge, what influence she had on his work but he was peaceful and safe with her.

“Anticipation”, Palestine, Warsaw

In 1928 Mrs. Stefa would often tell us she “had nothing left to do in Krochmalna Street” so when a new division of the Orphans’ Home for 50 children was opened in Gocławek [an eastern district of Warsaw], Mrs. Stefa took charge of it and helped with its organization. She would visit often. I worked there from the moment the preschool section was opened. Her visits were a joyful experience to us. She tried to settle all our doubts, tried to assist us. She taught us how to organize our work to save time, physical and mental effort.

But soon even this task was no longer enough for Mrs. Stefa. She began working with “Centos” [Headquarters of Societies for the Care of Orphans]. It was an association of the more progressive orphanages in Poland.

When one reads the few articles Mrs. Stefa left behind, you see what a person she was: forward-thinking, brave, uncompromising when it came to the good of the cause. Thanks to a report from six months of her work we can see how difficult the conditions were for children in pre-war orphanages.

Mrs. Stefa attempted to organize the children’s transitions from the orphanage into real life. Her notes on this issue she titled Próby uporządkowania czyli usuwanie bez bólu [The Attempts to Organize or Painless Leaving]. In this article Mrs. Stefa suggest that preparations for a pupil’s entrance into the world should begin as early as in the fall. Prepare clothing, discuss what they should do, if they want to move to one of the dormitories, remain for one more year to assist the orphanage’s staff, or return to their families. The ward should spend their last month at summer camp. The final year at the orphanage should not be filled with anxiety. It is always difficult to transfer from a good orphanage to independent life. Because if the orphanage is bad, if reluctance to pray is punished by withholding supper, then why bother removing the child from its previous miserable conditions? Bad orphanages should not exist.

And the ending surprises with its boldness since Korczak, despite his many doubts, despite often saying “who knows”, never questioned the issue of boarding in front of us. Even in the ghetto, facing extermination, he did not allow the children to return to their family homes, despite the voices suggesting it should be done.

Mrs. Stefa ends the article with doubts. Maybe boarding school is a thing of the past, maybe part-time boarding would be better? It would have the benefits of boarding and at the same time the child would not lose contact with their family.

Mrs. Stefa boldly brought the orphanages’ imperfections to light in her articles. No one else would have been able to get such words published. There names of board members or cities where the orphanages were located are not mentioned in the articles. There are only troubles, suffering staff and children.

You can learn from Ms. Stefa how to carry out an inspection. It seems to me that not only employees of orphanages can learn this, but also employees of other institutions. She preceded each visit with a letter that she was coming not as a criticizing auditor, but as a kind, experienced adviser.

Anticipation was her principle. She assumed that neither clean aprons nor good meals during the visit would be able to change the mood and atmosphere. To get to know a visited house better and more thoroughly, she always moved in (second principle). Mrs. Stefa watched and checked not what the children were eating but how they were eating. It was enough to know if the children were starving and how they were fed when she wasn’t there.

She spent the last months before the war in Palestine, visiting her beloved former student and helping her with the children in a kibbutz. She returned to Krochmalna Street in the early days of the war.

Doctor Korczak and Mrs. Stefa’s children went to the train cars dressed in their best outfits, marching in pairs. Each child had a travel bag slung over shoulder. At the head of the group Korczak led two of the younger children. That’s how those who were there to see it described it. We, Mrs. Stefa’s students, know that she was the one to prepare the outfits, instructing the children to fold them over the footboards and place their best shoes under their beds. So as to be ready to leave at a moment’s notice. She was responsible for the orderly and calm manner in which the children departed on their last journey.

Doctor Korczak and Mrs. Stefa’s children went to the train cars in their best outfits, marching in pairs. Each had its own travel bag slung over shoulder. At the head of the group Korczak led two of the younger children. This is what those who saw this extraordinary procession told. We, Ms. Stefa's students, know that she prepared Christmas clothes and instructed the children to fold them on the bed railing, and put the best shoes under their bed. To be ready to leave out at any time. She was responsible for the orderly and calm manner in which the children departed on their last journey.

Ida Merżan (1907-1987) – educator and journalist. In 1926 she began education at the Teachers’ Seminar in Warsaw and a year later began working at the Orphans’ Home at 92 Krochmalna Street, ran by Janusz Korczak and Stefania Wilczyńska. She later worked at the boarding pre-school “Różyczka” [Little Rose] in Otwock, and in the Orphanage for Abandoned Jewish Children. From 1928 involved with the Communist Party of Poland. She spent the war in the USSR, in Kharkiv, where she began studying part-time at the Institute of Pedagogy, and in Kazakhstan. After returning to Poland in 1945 she began working in the Central Committee of Polish Jews’ Child Care Department. The Committee was an organization established as a political representation of Jews towards the Polish authorities and looked after the Holocaust survivors.

Source:

Ida Merżan, Pani Stefania – najbliższy współpracownik Janusza Korczaka [Mrs. Stefania – Janusz Korczak’s closest associate], „Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego” [JHI Bulletin], no 4 (104), October-December 1977, p. 71-74. Subheadings were added by the editor.